Buying books in fifteenth-century Groningen

From the 1450s onwards, the invention of printing with moveable metal type spread throughout Europe, with the first printing offices appearing in many towns. Although no books were printed in Groningen until 1597, they were transported and traded, finding their way to the city and its surroundings. Books arrived from Zwolle and Deventer, the nearest printing towns, but also from places further afield, such as Venice or Basel. A wide variety of genres were on offer, ranging from theology to medicine and even classical poetry.

St Otgers market

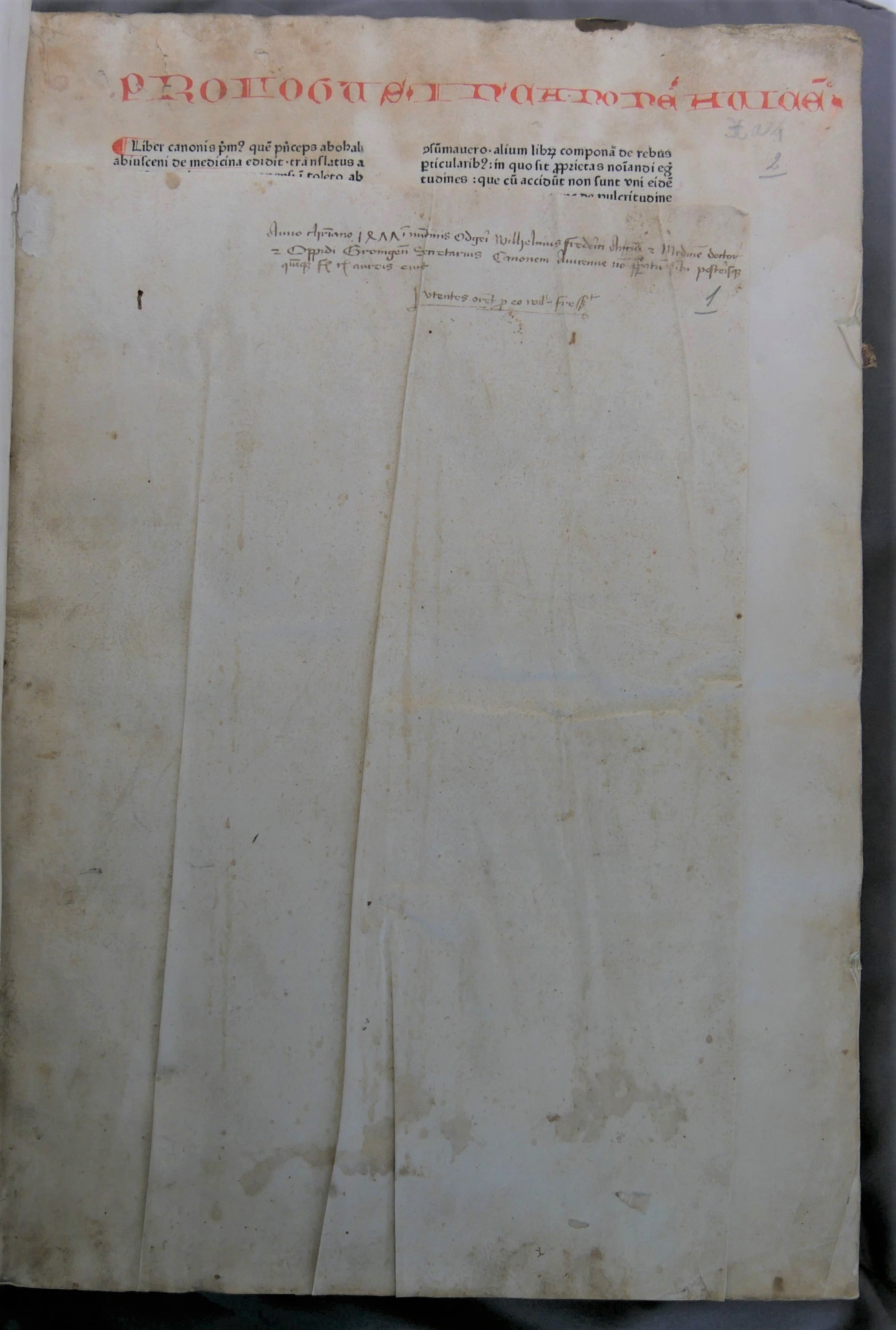

Where could one buy such books in fifteenth-century Groningen? One bibliophile who made careful notes in his books, thus providing us with valuable information, was Wilhelmus Frederici (1455-1525). In his day, Frederici was an influential figure in Groningen, as the head vicar of the Martinikerk, as secretary to the city, and as doctor artium et medicinae — he had received his doctoral degrees at Ferrara, with Rudolph Agricola among the witnesses. A number of the books he owned are currently held in the University Library. One was printed by Adolf Rusch in Strasbourg around 1473 and contains a medical treatise written by the Persian physician, astronomer and philosopher Avicenna (circa 980-1037). On a leaf that has been bound in with the copy, an inscription by Frederici reads:

Anno Christiano 1477 in nundinis odgeri Wilhelmus Frederici artium et medicinae doctor et Oppidi Groningensis secretarius Canonem Avicenne non praeparatum sibi posterisque quinque florenis rhenanis aureis emit. utentes orent pro eo. wilh. fre. scripsit.

This inscription recounts that Frederici acquired the book in 1477, about four years after it was printed in Strasbourg. He bought it for five gold Rhenish guilders (quinque florenis rhenanis aureis) at Saint Otger’s market (nundinis odgeri), which was the largest yearly market in Groningen, held around 10 September, the feast day of Saint Otger. As was common at the time, the book was ‘unfinished’ (non praeparatum), meaning that it had not been rubricated or bound. He therefore commissioned a rubricator and binder to do this for him.

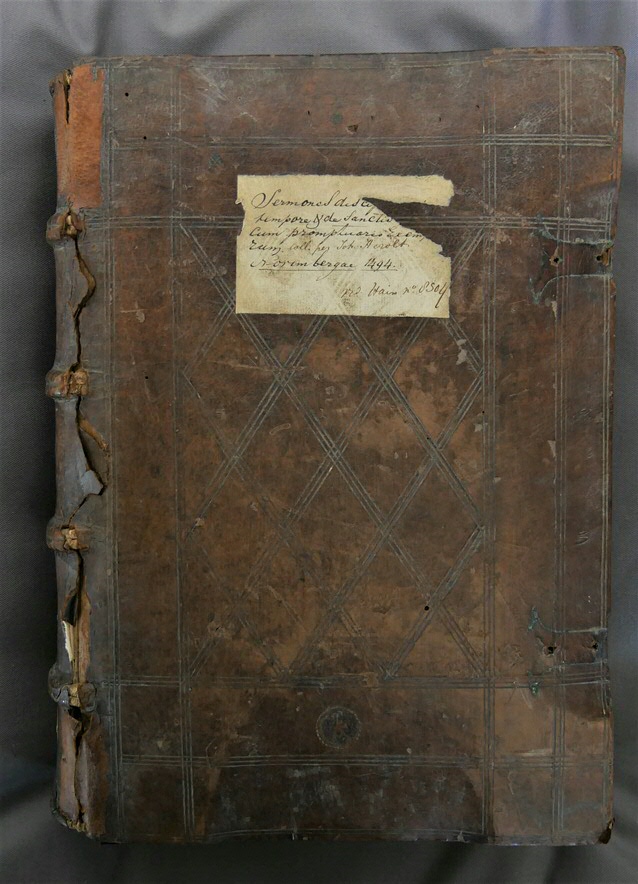

Rubrication is the manual addition of elements in red ink to the text. On this page it comprises a heading, a large initial ‘I’ and paragraph marks. These elements articulate the text’s structure, indicating where new paragraphs and chapters begin in order to help readers navigate their way through the book. The printed captions and page numbers that we know today were virtually unheard of in the fifteenth century and only became standard over the following centuries. The book’s binding is typical of the Groningen area, consisting of wooden boards covered in calfskin leather that is decorated with blind tooling, creating rectangular and lozenge shapes containing small stamps. Some small holes and dark brown patches at the fore-edge reveal where metal clasps had been attached to close the book, but these have unfortunately been lost.

The costs of binding a book

An even more detailed account of the costs is given by Hilbrand Wissinck, who was deacon and priest at the Martinikerk in Groningen around 1500. In 1497, he bought a book of sermons by the Dominican preacher Johann Herolt (also known as Discipulus), which had been printed three years earlier in Nuremberg by Anton Koberger. A Latin inscription in Wissinck’s hand reveals that:

Item monete 1497 sermones discipuli xxi stuferum planatura ii stuferum compactio decem stuferum hec simul computata faciunt aureum renensem ac septem stuferum hec acta 1497

He had purchased the book for 21 stuivers, he writes, apparently in unbound condition, as he had it levelled and bound for two and ten stuivers respectively. Wissinck’s inscription is written on a parchment leaf at the back of the book. It was reused from an older manuscript as a flyleaf in order to strengthen the book and protect the paper leaves of the textblock.