Lecturer’s Blog 10: "Learning from ancient scripture about learning in the (post) Covid times" by Padma Rao Sahib

Just as we scrambled to switch our teaching online when the corona pandemic started, this happened all over the world, even in some of the most unlikely places. This allowed me the opportunity to refresh my knowledge of Sanskrit (or Samskritam as it is properly called) through an online course from a centre for scriptural study in India in the hills of the Himalaya mountain range.

Samskritam, the ancient Indian language of India, has many aphorisms: pithy, sometimes cryptic statements that are meant to make us think and are considered to be full of wisdom.

There is one in particular caught my attention because it is related to how students learn. This is the subject of this blog.

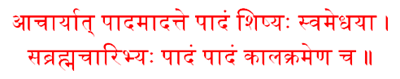

Just to get a feel for the beauty of the script, below is how this aphorism is written in Sanskrit in the original script:

The text in transliteration and an approximate translation (kindly contributed by Mr Shashi Joshi in his highly accessible PracticalSanskrit.com website) is as follows:

ācāryāt pādam ādatte

pādaṃ śiṣyaḥ svamedhayā |

pādaṃ sabrahmacāribhyaḥ

pādaṃ kālakrameṇa ca ||

ācāryāt = from the teacher, pādam = one-fourth, ādatte = [comes], pādaṃ = one-fourth, śiṣyaḥ = of the student, svamedhayā = [by] own intelligence, pādaṃ = one-fourth, sabrahmacāribhyaḥ = from fellow-students, pādaṃ = one-fourth, kālakrameṇa ca = in the course of time.

A quarter of a student’s learning comes from the teacher, a quarter from the student’s own intelligence, a quarter from fellow students, and a quarter comes with the passage of time.

The source and date of this verse seem hidden in antiquity, some claim this first appeared in the Mahabharata text (dated as far back as 3137 BC or as ‘recent’ at 1924 BC). In any case, for our purposes a very long time ago. It is comforting to know that even way back then, people thought about how students learn.

The verse is not surprising, while these exact allocations might be. For some of us it might be a relief to know that according to this verse, we are responsible for only 25% of students’ learning. So if you tripped up and solved an exercise incorrectly in class or forgot to explain an important point, worry not. Also, if you get a less than average teaching evaluation, this should be of comfort to you.

This may also explain how ‘unmemorable’ we are to students. I mainly teach first and second year students, and while I see some students for an entire 7 weeks, I am always surprised when some months later, they do not recognize me, walking past with a blank stare in the Plaza.

Also, that 25% of learning comes from the student’s own intelligence, need not surprise us. One might think this would actually be more, but perhaps we over-estimate how much our intelligence contributes to what we know.

Let’s focus on the other two. The first is that 25% of learning comes from other students. When we think of the period of the pandemic and the transition to online/hybrid education, which seems here to stay, it is this aspect in my opinion that has been affected the most.

During the lockdowns, when courses were entirely online, students had little or no contact with one another. The cohort of students which started as first year students in the academic year 2020-2021 saw one another only minimally. Some of them met their cohort-mates ‘in person’ only in their second year.

From informal chats with other instructors, it seems this cohort of students have not learnt what previous cohorts learnt through informal ‘in person’ chats in classroom, in the Plaza etc. Students are more inclined to send emails to instructors rather than ask class-mates. If we think of an idealized old fashioned response to a student missing a class, we may think of an earnest and sincere student who asks a fellow student for (handwritten) notes. Today students are more inclined to email an instructor to ask for a recording of the lecture, or perhaps there is already one conveniently placed in a folder on Nestor - so no need to ask a fellow student at all.

While it was great that our colleagues could put together e-learning tools for us to teach when the pandemic was upon us, some of the tools we have been using have not facilitated the interaction between students. Blackboard Collaborate lecture halls for large groups allowed students to only communicate via chat and students could in most cases not see each other even virtually. The ‘old’ rules of attendance requirements or incentivizing attendance in some way which were in place earlier years were mainly removed because we did not want students showing up and infecting others just to get their ‘attendance point’. However, such rules ensured a group of students showed up (some unwilling and unmotivated). While we no longer give points for attendance alone but link it to a task, the incentives to incorporate this in any substantive way are also made too cumbersome to impose because any task like this needs to be “resit-able.”

All this has implied that student attendance in this (post) Covid time has been poor. The few students that showed up often said that they don’t feel motivated to come because there are so few others in class. While attendance/participation rules are a contentious topic, they do seem to fulfill a function – at least in ensuring a critical mass of students show up.

The 25% of learning “that comes with time” is also something worth thinking about. Our current system of education places great emphasis on course evaluations. One of the standard questions in the course evaluation (administered within a couple of weeks) has a question in which a student can either agree or disagree with the statement “I learned a lot from this course.”

If a student disagrees with this and the instructor (heaven forbid) receives less than an A, the instructor has to “reflect” on this. This aphorism reminds us that sometimes knowledge needs stew in our heads before we know if what learnt was useful. So when a student emphatically writes “I did not learn anything in this course” perhaps it’s just not yet time.

With this, I pass the torch to my colleague down the hall, Andrea Kuiken who teaches some of the biggest courses in our Faculty.

Reference

https://blog.practicalsanskrit.com/2009/12/how-we-learn-and-grow.html Accessed 16 May 2022

| Last modified: | 23 September 2022 11.52 a.m. |