There once was a convent in Essen

Today, there is not really anything remarkable to see in this hamlet on the boundary be-tween Groningen and Haren: a farm, a few houses and trees. Long ago, women lived here in seclusion for nearly 400 years. They did not do this out of necessity, like we are doing because of the coronavirus, but of their own accord. They dedicated their lives to their faith by praying, working and living together, isolated from the rest of society in the Cistercian convent of Yesse, which was founded in 1215.

Around 1600, Ubbo Emmius also mentions the convent of Yesse.

In Rerum Frisicarum Historia (History of Frisia), he recounts: “Close to Groningen, a certain Theodoric, a priest in Groningen, founded a new convent around 1216, named after the place where it was founded: first Essen and, later, Yesse. It is now once again known by the first name. Small at first, it started to grow rapidly within a few years, as superstition had a strong hold on the people. It was home to a Cistercian family of young women under the leadership of an abbess.” (ed. 1616, p. 128) Around 1490, one of these young women was Ghebbe Canter. She came from a famous family in Groningen. Her father Johan was part of the Aduard circle of humanists, as was Rudolph Agricola. Her brother Jacob, an intellectual boy wonder, dedicated to her his book on the life and suffering of Jesus Christ published in 1489. Jacob calls Ghebbe "a learned young nun devoted to God in the famous convent of Yesse in Frisia."

That convent has long since ceased to exist.

There is no longer any trace to be found of the convent in Essen. The same is true of other convents and monasteries. Consider Selwerd. Now a district of the city of Groningen, it was once a village with a large Benedictine convent within a short walking distance from the city walls. Consider Aduard. Now a village on the outskirts of Groningen, it was once the site where the largest Cistercian convent in the North of the Netherlands dominated the country-side. Consider Wittewierum. It is now the home of a few houses and a church on a hill be-tween Damsterdiep and Eemskanaal. At one time, it was home to Emo, the abbot of the lo-cal Premonstratensian monastery, who, as a young man, had been the first foreign student in Oxford.

Nearly all of the convents and monasteries have disappeared from Groningen.

All of them were part of the Roman Catholic Church. For more than 1500 years, this Church was the only form of the Christian faith and, for hundreds of years, it largely coincided with society as a whole, particularly in Southern and Western Europe. The Church was the socie-ty. Everyone was Christian, and thus Catholic. This included the elite, who held the society in their political and economic grasp. The situation was no different in Frisia. This name was used to refer to the entire area between the Vlie and the Weser, and thus the current prov-inces of Friesland and Groningen, Northern Drenthe and German East Frisia.

For a long time this area lacked a strong sovereign.

For this reason, local rulers had a great deal of influence. This also included the convents and monasteries that were founded in this area in the second half of the 12th century. They played an important role in the agriculture and livestock farming, as well as in the reclama-tion and clearing of land in the region, where the sea had borne a great influence (both literally and figuratively) for centuries, due to the absence of coastal dikes. This gave convents and monasteries enormous social-economic and political clout within society. Moreover, as religious institutions, they also had clear moral authority.

The convents and monasteries emerged as part of a poverty movement.

This movement was a reaction to the enrichment and secularization of the Catholic Church. Many people desired to return to the simplicity and poverty of Christ and the ancient Church, to a life of seclusion, asceticism and prayer. These desires sparked the spontaneous emergence of communities of men and/or women that would become institutionalized into monasteries, convents and dual monasteries.

The monks and nuns chose to follow a specific Rule of life.

The most important was the Rule of Benedict of Norcia (Benedictines) which was established in the sixth century. This Rule also served as the basic principle for Robert of Molesme (Cistercians) and Norbert of Xanten (Premonstratensians), although they felt that, in their time, the Rule was not being observed nearly as well as it should be. It was for this reason that each of these men founded his own monastery: Robert in 1098 and Norbert in 1120. The names of their orders are illustrative of the ideal of the hermit, as they were derived from Cîteaux and Prémontré—the remote areas in France where they established their first mon-asteries.

In Frisia convents and monasteries emerged on personal initiative.

They were not founded as the result of any great plan of a bishop or church, but due to personal circumstances, as individuals were continuously feeling called to found such communities. The monastery in Wittewierum provides the best example, as we are able to read about its beginnings in a contemporaneous personal report. It was not until after a convent or a monastery had been founded that the nuns and monks would ask to be admitted to a par-ticular monastic order.

In the late Middle Ages convents and monasteries were scattered throughout Groningen.

In his Rerum Frisicarum historia [History of Frisia], Ubbo Emmius mentions this as a charac-teristic of the area: “Frisia between Lauwers and Eems is special due to its buildings and wealth. The area has 25 convents and monasteries: first of all, Aduard ... and then near Ap-pingedam and in Marne, Warffum, Rottum, Thesinge, Selwerd, Schiermonnik, Wittewierum, Heiligerlee, Schildwolde and, finally, Yesse, not far from the city limits of Groningen, on its outskirts. Miraculously, generous kings or princes did not contribute to them at all. The ef-forts of the rural population and a few members of the nobility brought about what is a relatively large output for such a small and poor area.” (ed. 1616, p. 20)

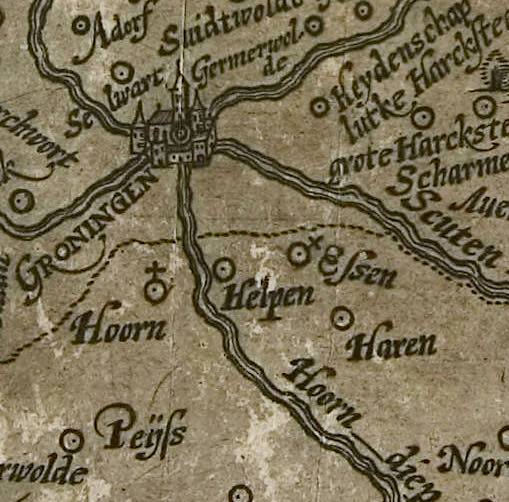

Most of the convents and monasteries (including Yesse) can be found on this map.

It was primarily the Benedictines, Cistercians and Premonstratensians who would found the first convents and monasteries around 1200. For example, the Benedictines could be found in Feldwerd, Rottum, Ten Boer, Thesinge and Selwerd. The Cistercians were located in Rinsumageest, Aduard, Essen, Marum, Midwolda, Nieuwolda and Termunten. Premonstratensian convents and monasteries could be found in Kloosterburen, De Marne, Krewerd, Schildwolde, Heiligerlee and Wittewierum. These three monastic orders would remain the wealthiest, with the greatest landholdings for centuries to come. It has been estimated that one third of the land area was in their hands. Moreover, a third of the population was involved with the convents and monasteries in some way, as tenant farmers, converts (lay religious), monks or nuns.

The land area of a convent or monastery was often extensive.

For this reason, convents and monasteries founded grangia (monastic granges and folwarks): small settlements where a few monks and lay brothers living on the site were charged with activities relating to agriculture and livestock farming. For example, the convent of Yesse owned several tracts of land, forests and windmills in Groningen and Drenthe. Even before 1249, it acquired land near Kropswolde for purposes of peat cutting. The monastery in Rottum also had landholdings here. The Aduard Abbey was present in adjacent Wolfsbarge. The concept of a voorwerk (folwark) still appears in the present-day names of towns, like Aduarder Voorwerk, Fransumer Voorwerk and Westeremder Voorwerk.

Beginning in 1517 everything changed.

Martin Luther revolted against the Pope and the Church. Christianity would soon split into a Catholic and a Protestant fragment—the beginnings of years of war and violence. In Groningen, the Protestants would eventually win this battle decisively in 1594, with the conquest of the City of Groningen, which, until that time, had been a stronghold of Spain. This would come to be known as the Reduction, as the City and Province were now part of the Republic of the United Netherlands. All of the convents and monasteries were immediately dissolved, plundered and demolished. Many of their bricks were used to build the houses and villages that are now located on the same site where the convents and monasteries once stood.

Sources

- C. Damen, Geschiedenis van de Benediktijnenkloosters in de provincie Groningen (Assen 1972)

- B. Flikkema, Turfgraven en bidden. Aanwezigheid en sporen in Kropswolde van het vrouwenklooster Yesse te Essen (Haren 2014)

- G.C. Huisman & C.G. Santing, Wessel Gansfort en het Noordelijk Humanisme (Groningen 1989)

- Kloosters in Groningen. De middeleeuwse kloostergeschiedenis van de Nederlanden deel III, ed. M. Hillenga & H. Kroeze (Zwolle 2011)

- J.J. Vredenberg-Alink, De kaarten van Groningerland. De ontwikkeling van het kaartbeeld van de tegenwoordige provincie Groningen met een lijst van gedrukte kaarten, vervaardigd tussen 1545 en 1864 (Uithuizen 1974)

| Last modified: | 29 June 2021 09.09 a.m. |