The Groningen Academy and the Relief of Groningen

1672 is known as the ‘Disaster Year ’ in the Netherlands. The government was reckless, the people witless, and the country hopeless, or so the popular quotation which became a cliché went. The enemy was invading from all sides: the French from the south, the Germans from the east, and the English by sea. Helping the latter was at least partly the goal of the German enemy, but it failed, because the tide turned midyear and the Dutch victory began—from Groningen.

The Academy and the Relief of 1672

This map, drawn in 1674, is a reduced version of Jannes Tideman’s original version on parchment which is now in the Groningen Archives. It shows the enemy doing his very worst. For a whole month long, the two bishops’ troops had besieged and shelled the city. The enemy troops only occupied the south of the city, because the Groningen residents had flooded a large part of the surrounding countryside. Thus, the city could not be surrounded and could not be shelled from all sides. This also allowed the supply of food, equipment, and troops to continue. Stationed at the south of the city, however, was a large army of more than 20,000 soldiers—from the Herepoort and Oosterpoort city gates via the village of Helpen (now the city borough of Helpman) to Haren.

The city was heavily damaged from the south. This print explicitly and ornately shows bombs and grenades falling on the city in large numbers. Added below the print is a ‘sincere story’ that describes events in detail. The north of the city was largely spared, simply because the range was too great for the enemy guns—another advantage of the inundation. The Groningen Academy was also located in this northern part of the city, on the same spot where it was founded in August 1614: on the Broerstraat, with the Academy Building at the north end of the street and the University Library to the south. The professors and students of the Groningen Academy also played a role in the active defence of the city.

As the title ‘Journal’ suggests, the author provides daily reports of the Siege of Groningen here. That author was Andreas Eldercamp. He was a pastor in Lutjegast, so it is not surprising that he turned out to be a good storyteller. After all, pastors had to captivate their audience every week and rhetoric was an important part of their training. Eldercamp was a vivid raconteur and he enlivened his report with many anecdotes. For example, he reports on Thursday 8 August (old style): ‘A fire-bomb from Drenckelaers Dwinger fell on a wagon, which the Devil’s work set two tons of gunpowder alight, blowing the heads, arms, and legs of its mutilated victims like straw in the air.’ (p. 13)

The Groningen Academy also plays a role in this Journal. For example, on Thursday 25 July, we read: ‘Due to good advances from Hoogheyt, we were sent auxiliary troops from Friesland, three and a half hundred men, who were quartered at the Academy.’ (p. 9) Eldercamp also repeatedly mentions the contribution of the approximately 150 students who helped defend the city. They were one of the companies formed in preparation for the Siege. The students did this voluntarily. Formally, like the professors, they were exempt from military service, but they turned out to be actively and enthusiastically willing to fight for their freedom. They did this under the leadership of their own captains, the students Wicher Wichers (captain), Rutger ten Berghe (lieutenant), and Scato Gockinga, who carried the banner that has been preserved.

The professors had drawn up rules for the students’ conduct. In the University Library, which was located in the former Franciscan church on Broerstraat, on the exact spot where the University Library still stands, two students worked night shifts as firefighters.

Eldercamp explicitly mentions the students three times in his journal (ill. 5-6):

(Friday July 26, on the occasion of an unexpected alarm) ‘With a wonderful and widespread call to attention, all the men took up their arms and ran to their ordained posts; the residents of our High School and our citizens were the first to the march.’ (p. 9)

‘Sunday the 28th. In the night there was again an alarm, and the students, citizens, and all the militia took up their arms, and marched together to their posts.’ (p. 9)

(Friday 16 August) ‘... and it happened in the afternoon, that a troop of irregular infantry, among whom many volunteer students and citizens, did sally forth under the command of Master of the Guard Willers, who led this troop unshakably and valiantly to and into the enemy’s trenches. Those from the Guard that night set about them with more carefree abandon than before; those who came under our fire were shot, and put to the sword and pike.’ (p. 15)

After the liberation was achieved, the city of Groningen decided to commemorate its relief every year on 17 August, the first day on which no further hostilities occurred. This was the date according to the Julian calendar (or ‘old style’), which was used in Groningen up to and including the year 1700—and thus also by Eldercamp in his Journal. In the Gregorian (or ‘new style’) calendar, which we still use now, 17 August became 28 August. That is why the City has been celebrating the Relief of Groningen on that date since the eighteenth century.

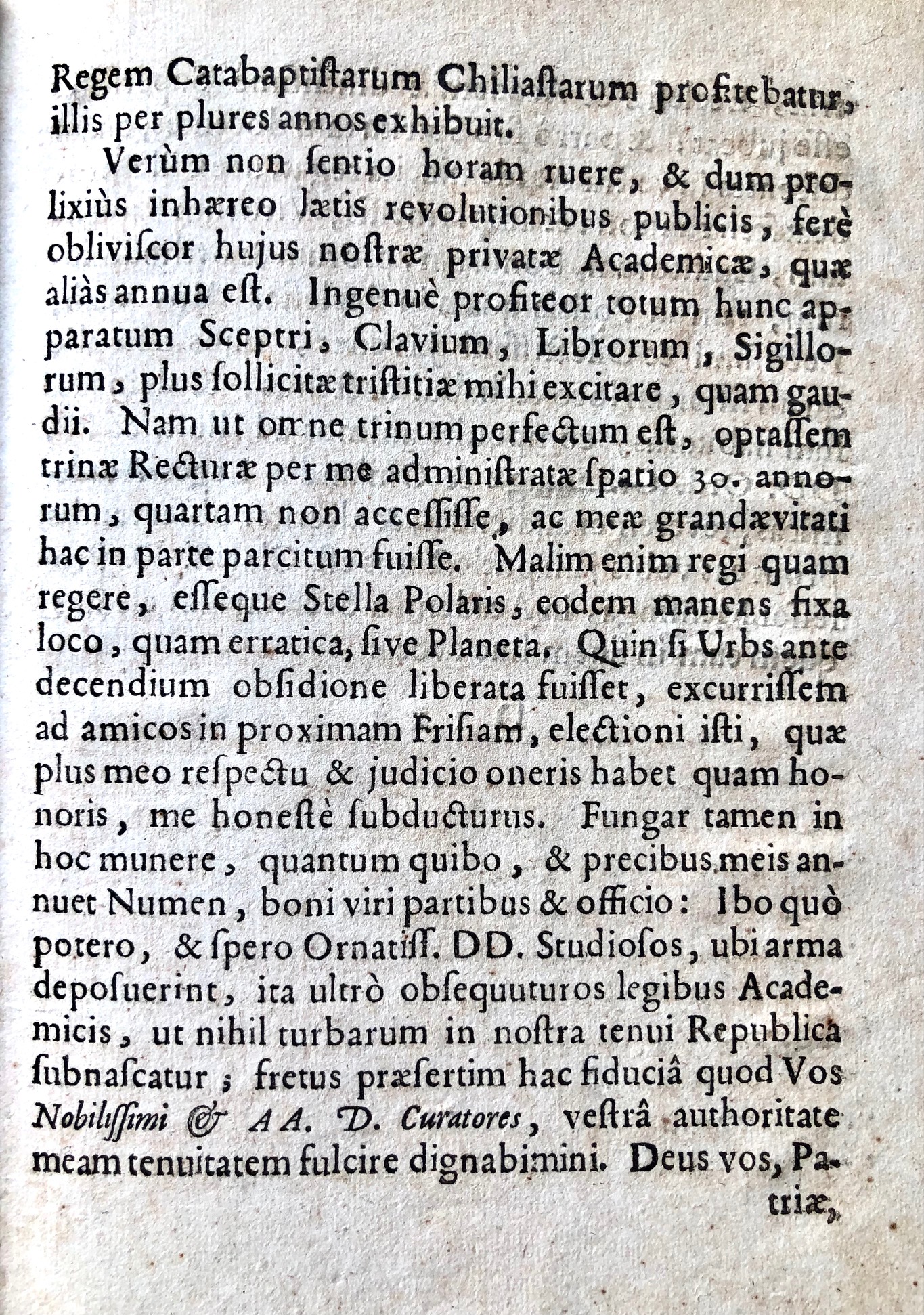

The fighting thus ended on 17 August. Just six days later, on 23 August, Rector Magnificus and Professor of Theology Samuel Maresius opened the new academic year with a speech, as is still customary today. He took the opportunity to look back on the turbulent year as it had gone so far and, in particular, on the recently ended Siege. He obviously had nothing good to say about the bishops of Münster and Cologne. In his eyes, they were worse than the heathen Alexander the Great, who had at least wanted to win honestly. The bishops were more like Alexander’s father Philip: (a3r-v) ‘Alexander the Great never wanted to steal his victories, but our enemies preferred payment, and would rather win their victories with money than with sweat and blood. In this they followed the tactics of Philip of Macedon, who stated that any city to which you could bring a mule packed with gold could be conquered.’ Maresius then lets out a sigh in the form of a quote from the famous epic poem Aeneid by the Roman poet Virgil, that is still relevant today: Quid non mortalia pectora cogis, Auri sacra fames? ‘Cursed hunger for Gold, what can’t you make people do?’ Fortunately, ‘Bombing Bernard’ met a worthy adversary in Groningen: (b4v) ‘Groningen was too innocent a woman to have to succumb to such an impure priest, yes such a filthy devil. Elsewhere you have found merchants and women, you tout for Christ, but here were men and soldiers. You came and saw, but did not conquer. In the end you were put shamefully to flight.’

As could be expected from an orthodox theologian and protestant, Maresius points to the grace of God as the true cause of victory, but in this context the students were also mentioned: (c1v-c2r) ‘He is our God, who has urged also you, noble and distinguished gentlemen students, to take up arms in defense of the homeland, the Church and the academy, to contribute to the vigorous defense of the city, and to adopt as your creed what was once that of the famed Duplessis-Mornay: With skill and struggle.’

These words are part of a long passage in which Maresius addresses the students present directly and discusses their active role in the Relief of Groningen. His whole address again clearly testifies that education in the non-Christian culture of Graeco-Roman Antiquity had been an essential ingredient of academic education in Europe for centuries until that time, even of strict Christians such as Maresius. He notes that God had protected Groningen against every weapon, as Athena, according to Homer, did for Menelaus (c2v).

As mentioned, the professors had drawn up rules for the students in the hope of moderating their behaviour. That appears not to have worked during the Siege. In his address, Maresius made a fresh attempt, but he does not seem very reassured: (c4r) ‘I hope that you, dear students, as soon as you have laid down your arms, you will of your own accord obey the academic rules, so that no riot occurs in our fragile republic. In this hope, I am particularly reassured that you, reverend Curators of the Academy, will wish to support my frail position with your authority.’

It will therefore not have been without reason that Maresius closed his speech with an urgent admonition to the ears of the students present: (C4v) ‘Select and precious young men who I have always regarded as sons, and shall continue to do so, respect and enthusiastically observe the academic rules of the States of Groningen and Ommeland, as they will now be read to you ... by Professor Mensinga, who has been elected secretary of the Academy. To that end I now call him forward. I have spoken.’

Three months later, on 8 November 1672, this Johannes Mensinga—professor of rhetoric and a native of the city—spoke also during a meeting at which the students from the militia were awarded a silver medal for services rendered during the Siege of Groningen. Until that day, the students had remained formally under arms. In his festive speech, Mensinga pulled out all the stops.

Materially, the Groningen Academy had come out of the battle almost unscathed because of its favourable location in the north of the city centre, at a relatively great distance from the enemy guns. Yet the consequences of the Siege were also significant for the University. Some of the students had temporarily left the city, lectures had been halted for a long time and Groningen had not exactly become more attractive as a student city. Only 43 students enrolled for the 1672–1673 academic year. In the last quarter of the seventeenth century, the decline in the student population continued. New growth and flowering would be a long time coming.

Theodorus van Swinderen and the Commemoration

The Relief of the city of Groningen in August 1672 gave rise to commemorations and celebrations which continue to this day. 28 August (‘new style’) was immediately declared an official day of thanksgiving and a holiday by the city council. The emphasis was on religious commemoration: meetings were held in the morning in all the main churches on that day. And although there is also talk of ‘celebration’, there will initially have been little opportunity for this. 28 August has been commemorated in this way for 123 years.

With the arrival of the French in 1795 and the establishment of the Batavian Republic, this tradition came to an abrupt end. Celebrating the defeat of a French ally did not help, of course. However, the departure of the French and the establishment of the United Kingdom of the Netherlands did not mean that commemorations could resume as usual. Perhaps the end of the aforementioned United Kingdom was one of the reasons for the reintroduction of the holiday and anniversary. The Belgian Revolution of 1831 and the subsequent split of the Kingdom aroused nationalistic feelings in the Northern Netherlands, in which the struggle for the fatherland by the ancestors regained in importance.

The renewed focus on the battle in the Disaster Year of 1672, in which the Groningen residents played a heroic role, also fitted this context. In any case, in 1838 a petition by prominent Groningen citizens was granted by the city council. Immediately in that year, there was already a commemoration and celebration. In 1838 the time for making preparations was too short, but in 1839 the liberation was celebrated on a grand scale. From that moment on, the ‘popular entertainments’ took on an increasingly important role, with recognizable elements such as a parade, flag display, children’s games, and fireworks. In addition, ‘gymnastic exercises’ were added to the programme in 1839. Special equipment was developed and constructed for this purpose. The Groningen teacher R.G. Rijkens played an important role in this. He is considered one of the founders of Dutch gymnastics training. This equipment was used successfully for the first time at the celebration in 1839.

Theodorus van Swinderen (1784–1851), professor of natural history at the University of Groningen from 1814 until his death, was a versatile man. He founded the Royal Physics Society and took the initiative to set up the Museum of Natural History. But he is also known for wanting to increase the historical awareness of the inhabitants of the city and the province of Groningen. It is therefore not surprising that he was one of the initiators of the reintroduction of the festivities on 28 August.

Van Swinderen describes the course of the day in detail in 1839 in his brochure (ill. 14). The city was decked with flags. The poor were also remembered, ‘a thousand currant loaves, each with a fourth of a pound of cheese’ were distributed. At ten o’clock, the traditional worship services began in the churches, during which a Groningen victory song was also sung. In the afternoon there was a parade by the Groninger Schutterij (the Groningen national guard or militia) and the national anthem, the ‘Wilhelmus’, was played. The abovementioned gymnastic games were held at a site outside the Herepoort. It must have been a heartening, festive sight: the gymnasts in ‘their clothes made for this celebration, consisting of long white trousers, white shirts, and round white straw hats, in the old patriotic style, folded on one side, and also decorated with orange ribbons and fresh oak sprigs.’ According to Van Swinderen, the games were attended by more than 10,000 spectators. In the evening there was music on the Grote Markt and the play ‘The Triumph of Groningen’ was performed. Here were also ‘harmless fireworks’ and bonfires. Thus ended this festive day and the tradition of a folk festival, as it has been celebrated ever since, began.

The Relief of Groningen in Youth Literature

The abovementioned gentlemen Rijkens and Van Swinderen clearly understood that, in order for a tradition to live on, it is of the utmost importance to involve young people in this tradition. Their gymnastic exercises are a good example of this. But from the outset, the enthusiasm of young people was also stimulated through literature about the exciting story of the siege and the relief. Almost immediately, booklets and pamphlets were published about the events in 1672, especially intended for young people. The best known and most gruesome example of this is the Nieuwe Spiegel der Jeugd, of France Tiranny; Zynde een kort Verhaal van d’Oorspronk en voortgang des Oorlogs 1672. Als mede de schriklyke en onmenslyke wreedheyd en gruwelen, door de Fransen in Nederland, en elders bedreven. (‘New Mirror for Youth, or French Tyranny, being a short story of the origin and progress of the war of 1672, as well as the terrible and inhuman cruelty and atrocities committed by the French in the Netherlands and elsewhere.’) According to the subtitle, this book was ‘Very useful and helpful to be taught in schools.’ Originally published in 1674, this work was reprinted many times. The edition in the possession of the University of Groningen Library dates from the late-18th century. The atrocities committed by the French troops are described in lurid colours. Incidentally, the Nieuwe Spiegel does not report on the French allies in 1672, such as the troops of the Bishop of Münster.

Two other booklets for young people concern the events in Groningen. 1672, 28 Augustus, de belegering en verlossing van Groningen aan kinderen verhaald (‘1672, 28 August, the siege and redemption of Groningen related to children’) appeared around 1875 (ill. 18). Its author was Aart Cornelis de Zwart (1836–1885), who was a head teacher in the city of Groningen for a while and is known as the author of more than thirty Christian children’s books. This work about 1672 is also strongly religious in nature and, according to the preface, is intended as a festive gift through which the youth of Groningen will hopefully get to know the reason for and the higher purpose of the entertainment. ‘National feasts are excellent, so long as the God of our fathers is not forgotten.’ Miraculous escapes from the terrible fate threatened by the bishops’ bombs are described as proof of God’s providence. The book may have been published in 1872 on the occasion of the second centenary of the commemoration of the relief.

About 25 years later, the book 1672, of Het beleg en ontzet van Groningen (‘1672, or The siege and relief of Groningen’) was published. The University of Groningen Library owns a second edition, which will have been published after the death of its author, Piet Louwerse (1840–1908). This edition has a beautiful title plate by Jan Wiegman (1884–1963), which accurately reflects the atmosphere of the book. Louwerse tells the story of the Siege through the eyes of four boys who actively help to defend Groningen. While trust in God was central to A. C. de Zwart, Louwerse has a fiery national awareness and a great ‘Orange spirit’. Orangism is clearly ‘above’ Groningen here. In this sense he is in line with what Theodorus van Swinderen also intended: a national feeling, revolving around the throne and in trust in God.

Sources not mentioned in the text

- Groningen Archives, Kerkelijke gemeente Groningen, Ondertrouwboek 1653-1656, archiefnummer 124, Doop-, trouw- en begraafboeken enz. in de provincie Groningen, inventarisnummer 166, blad 5v

- Klaas van Berkel, Universiteit van het Noorden: vier eeuwen academisch leven in Groningen. Deel I: De oude universiteit, 1614-1876 (Hilversum: Verloren, 2014)

- Nicoline van der Sijs and Arthur der Weduwen, Franse tirannie: het Rampjaar 1672 op school (Zwolle: Waanders, 2022)

- Wouter van Raamsdonk, “ Bommenberend voor schooljongens verklaard ” in Groniek, 172 (2006), 355-369

![Maresius, Discursus [Address], fol. b4v](/library/_shared/images/BC/groningens-ontzet-350/go350-expo-09.jpg)