Giuseppe Bottai

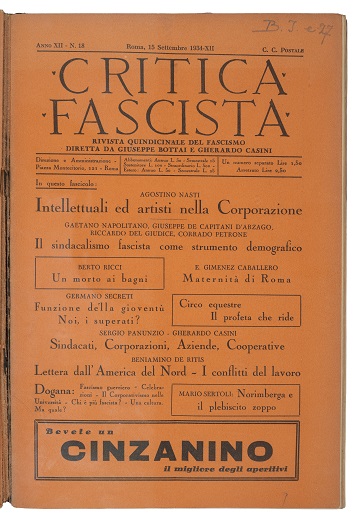

Giuseppe Bottai was an interesting and sometimes highly contradictory character of the era of fascism. During his life, he worked as a politician, soldier, and journalist. In 1923, at the age of 28, he founded Critica Fascista, a periodical initially supported by Mussolini, who appreciated part of its criticism of (fascist) culture and politics. This periodical is cardinal evidence of a form of fascism not in line with the mainstream. In 1924, Bottai founded another periodical, a precursor of Il Primato, Lo Spettatore Italiano, to which authors such as the Nobel Prize for Literature laureates Luigi Pirandello, Umberto Saba, Giuseppe Ungaretti, Emilio Cecchi, and Ettore Lo Gatto contributed articles on literature.

From 1926 to 1932, Bottai worked at the Ministry of Corporations (Ministro delle Corporazioni), the administrative organ overseeing the Italian labour market and the economy – first as undersecretary of State (1926-1929) and then as minister (1929-1932).

In 1940, Bottai founded the magazine Il Primato, which had more of an emphasis on culture. This specific magazine is a testimony to Bottai’s radical and germanophile ideas. After the fall of the Fascist Regime and subsequently, when he was able to come out of hiding, he dedicated all his time to editorial work. In 1947, his life sentence was revoked. In 1950, he founded yet again another biweekly political magazine, ABC, which was instrumental in debating the fascist experience and the new democratic journey.

Education and Initial Upbringing

Bottai was born in Rome as part of a firmly Republican and atheist family. His mother was a supporter of Giuseppe Mazzini – head of the Italian revolutionary movement and republican proponent – and his uncle was a solid antifascist. His family often reunited with fellow Mazzinians and antimonarchists. Bottai himself was initially a Republican. His youth was dedicated primarily to his literary studies. However, despite his dedication to the arts and humanities, his attraction to politics seems to have been a natural disposition.

Adhesion to Fascism

Barely in his twenties, Bottai enrolled as a volunteer during WWI in the Italian army. He later declared in an interview that the war had changed him. After his return, he decided he wanted to be amongst those in charge of political changes. This is why he was attracted to the strong impetus of the National Fascist Party which was driven by the strong leader-figure in the form of Benito Mussolini. His first approach to fascism was in 1919 when he encountered Mussolini in person. Bottai participated in the foundation of the Italian Fasces of Combat, the first fascist organisation created by Mussolini, marking the beginning of his political career.

Interestingly, in 1943, when it became obvious that Mussolini’s regime was over, Bottai openly adhered to L’Ordine del giorno Grani, a commission that aimed to put Mussolini aside.

An Ambivalent Figure

One of the interesting aspects that characterise Bottai’s ambivalence is his sudden shift towards antisemitism. Before his involvement in the fascist movement, there were no records of antisemitic tendencies, and his embrace of racism and antisemitism hardly found a satisfactory explanation. During his secondary school career at Liceo Classico Tasso in Rome, he had many Jewish friends. Later in his life, he co-founded the journal Critica Fascista with Gino Modigliani, a Jew. Additionally, some of his closest friends and collaborators – Enrico Rocca and Gino Arias – were Jewish. This changed in 1938, when Bottai fully embraced Mussolini’s antisemitic ideals. Subsequently, Critica Fascista started publishing antisemitic essays. Perhaps, this turn was even a strategic response to his ‘enemies’ who accused him of being Jewish due to his physical appearance – darker skin, black hair, and dark eyes. Yet the true reason for this sudden turn remains vague.

On the one hand, Bottai was a highly cultivated, critical, and complex man; on the other hand, an intransigent and fervent supporter of the regime. Nevertheless, Bottai is surely a notable figure for bringing forth a critical analysis of the fascist period from within.

Subordination of the Press, Arts, and the Artist.

Bottai believed in strict cooperation between intellectuals and the fascist ruling class, by which he meant that intellectuals should serve politics and fascist reform. This was his greatest ambition. Interesting is the position of writer Antonio Aniante (aka Antonio Rapisarda), who sustained the fascist propaganda by arguing that only one who tenaciously follows fascism, respects hierarchy, and loves the nation, can be called a genuine fascist writer. According to Aniante, ‘forms of literature that glorified class struggle, internationalisation, and any type of racial desegregation’ were to be repudiated.

The fascist reform of the arts is amply reflected in Critica Fascista, where Bottai meticulously reported Mussolini’s words. An instance of this phenomenon is Mussolini’s speech at the Accademia di Belle Arti in Perugia in 1926, where he declared the need for an art form essentially mirroring politics. The vigorous debate that this speech instigated, which was analysed shortly thereafter in Critica Fascista, revolved around notions of art in its relationship to fascism.

In 1927, Critica Fascista collected the opinions of different artists, agreeing that, in the end, art should be motivated by the same tendencies as ‘the political arena’ and show itself to be ‘militantly faithful to the fascist cause’. Its aim was clear: to subordinate various free artistic disciplines to the political ideology of fascism. Using Bottai’s influential magazine was a successful way to exchange artistic originality for conformism to the regime.

All in all, Bottai’s success in spreading the fascist doctrine also came from the fact that he managed to surround himself with (young) intellectuals, who regularly published in the Critica Fascista and saw Bottai as a point of reference. He did the same with collaborators who stayed by his side during his period in the government. Bottai’s predilection for (young) intellectuals reflected his efforts to patronise Italy's most talented artists and writers, regardless of their political views.

Critica Fascista and Antisemitism

As mentioned, the magazine did not originate as an antisemitic journal, but rather as a medium for Bottai to discuss and spread his opinion on fascism. Not only the magazine’s co-founder and patron, Gino Modigliani, was Jewish, but so were many of Bottai’s intellectual friends, including his closest friends Enrico Rocca and Gino Arias, who were some of the most frequent collaborators of Critica Fascista. Because of its original purpose, the magazine never published anything antisemitic until Bottai’s embrace of Mussolini’s antisemitic standpoint and the Leggi Razziali in 1938. At that point, he started publishing large numbers of antisemitic essays, arguably turning the journal into ‘one of the most influential sites in the campaign against the Jews’ – at least for the following year and a half. Cases arose where opportunistic young intellectuals (who later considered themselves ‘redeemed’) took part in the vile campaign of antisemitic pieces, once the racial campaign began in 1938. Writer Guido Piovene is an example of this. Despite having a Jew, Eugenio Coloni, as his dearest friend, he indulged in ‘the crudest characterizations of Jews and Jewish culture’.

Education Reform

A small number of copies of the Critica Fascista in the Bibliotheca Italiana concerns the Fascist reform of the schools. Bottai was actively involved in this, both as a political figure and as a journalist spreading fascist propaganda. The school was a crucial area for fascists to indoctrinate younger generations into the ‘myth of fascist politics and culture’.

Bottai’s school and cultural reform did not only mean the removal of Jews from cultural life, expelling teachers and students from public schools, but also removing books written by Jews from public libraries.

While Bottai worked as Minister of National Education, he dedicated himself entirely to radicalising the schools. This was supported by his idea that ‘fascism should give birth to a permanent revolution’. In his Critica Fascista, Bottai complained that it took too long to let the schools abide by the fascist doctrine. Driven by his desire to reform schools, Bottai presented La Carta della Scuola to the Gran Consiglio del Fascismo in 1939. The fascist propaganda took place all around, via Bottai’s ministry position, his periodical Critica Fascista, followed by others, and the involvement of the youth in the National Fascist Party.

Labour & Corporatism

The largest part of the Critica Fascista in the Bibliotheca Italiana concerns fascist corporatism.

Corporatism is the theory and practice of organising society into ‘corporations’ subordinate to the state. In these corporations workers and employers would be organised in industrial and professional corporations which would serve as organs of political representation, to a large extent controlling the persons and activities within their jurisdictions. The fascist regime put into effect the theory of a ‘corporate state’, however, it ended up reflecting Mussolini’s will rather than the interests of economic groups.

Bottai’s efforts indicate a solution in conformity with the system, which for the fascist regime meant the way of corporatism. He advocated a solution to the crisis that encompassed a reorganisation of the state in a way that would privilege the public sector through corporate state controls and the regulation of non-corporate cartels. Bottai theorised a ‘totalitarian corporatism’ as the foundation of a 'participatory' Fascism resting on popular support. De facto, one of Bottai’s aims was to gain favour among the workers by affirming the ‘revolutionary’ and anti-bourgeois spirit of the dictatorship and labour unions. Critica Fascista played a big role in voicing these opinions of the ‘Fascist Left’.

Overall, Critica Fascista, including the copies present in the University Library, remains an important testimony to fascist culture. While it showcases specific aspects typical of the fascist regime, such as the creation of a strong leader and antisemitic messages, it also shows different aspects, in particular regarding the discussions and inclusion of different standpoints, which were occasionally of a leftist or international nature. This cannot be seen separately from the man who ran the magazine for its entirety, Giuseppe Bottai, whose ambivalence towards fascism made Critica Fascista the important window into the fascist period that we can study today.

| Last modified: | 22 July 2024 3.42 p.m. |