Het tijdschrift Critica Fascista

Fascistische pers

Gedurende de gehele twintigste eeuw ontstond er een veelheid aan tijdschriften waarin intellectuelen, schrijvers, filosofen en politici de discussie met elkaar aangingen en waarin nieuwe literaire genres werden geïntroduceerd en uitgeprobeerd. Ieder tijdschrift is een weerspiegeling van de samenleving waaruit het is voortgekomen. Het verwoordt de ideeën en discussies die in die samenleving leven. Van de fascistische tijdschriften was Critica Fascista het meest toonaangevend, om verschillende redenen: ten eerste vanwege de omstreden oprichter en redacteur Giuseppe Bottai; ten tweede vanwege zijn culturele getuigenis van het fascisme, waarbij binnen het regime een enigszins links standpunt werd ingenomen dat blijk gaf van openheid voor internationale cultuur; ten slotte, omdat het niet altijd meeging in alle aspecten van de fascistische leer.

Critica Fascista in de fascistische pers

Critica Fascista maakte deel uit van de voor fascistisch Italië kenmerkende propagandistische pers. Al snel werd het vanuit het oogpunt van de politieke en culturele debatten van die tijd een van de belangrijkste tijdschriften. Veel critici zagen Bottai als een gematigde of zelfs ronduit kritische fascist. De kritische houding van het tijdschrift tegenover het fascisme ondersteunt deze visie, maar kan deels verklaard worden door de culturele en intellectuele klasse van het lezerspubliek. Hoewel Bottai Mussolini 'verraadde' en zich de rest van zijn leven probeerde los te maken van zijn onverzettelijkheid tijdens het fascistische tijdperk, bleef hij een van de belangrijkste en meest fervente voorstanders van het fascistische totalitarisme.

Critica Fascista promootte niet alleen het fascistische totalitarisme, maar diende ook als 'verlosser' en 'degene die het laatste woord heeft' in discussies over het fascisme. Bottai wilde nieuwe technische en culturele elites creëren, en drong daarom met hulp van zijn medewerkers en via het tijdschrift aan op een volledige modernisering van 'alles wat Italiaans was'.

Het fascistische regime streefde naar een uniforme pers en nieuwe journalistiek, die, net als de regering, onversneden fascistisch moesten zijn. Mussolini probeerde aanvankelijk tot op zekere hoogte een 'gematigde aanpak' te hanteren, maar koos later toch voor centralisatie van de pers, die de journalisten weinig tot geen onafhankelijkheid liet. Er werd een 'zuiveringsactie' in gang gezet ter voltooiing van het project waarbij de Italiaanse pers en journalisten volledig moesten gehoorzamen aan het fascisme. In september 1928 publiceerde Mussolini’s persbureau een gedragscode voor de pers. Het doel daarvan was het voorkomen van ongewenst nieuws, zogenaamd om de moraal van de Italiaanse samenleving op een hoger plan te brengen. De pers werd hét medium voor fascistische propaganda en monopoliseerde het debat, waarbij gehoorzaamheid van het collectieve denken aan het regime werd gestimuleerd.

De dagbladen waren het meest uitgesproken in hun steun, tijdschriften waren minder expliciet en boden ook ruimte aan meerduidige ideeën. De tijdschriften — met name de sociaalpolitieke tijdschriften — waren gericht op jonge leden van de fascistische partij en studenten. Ze waren bedoeld om de discussie over het fascisme te manipuleren en te verstoren, met als uiteindelijke doel het publiek te betrekken bij het heldenverhaal van het Italiaanse fascisme. Om dit doel te bereiken, moest het publiek het succes van de Duce en van de fascistische doctrine steeds zien en beleven door middel van afbeeldingen, drukwerk en intellectuele tijdschriften die allemaal in dezelfde richting wezen. De fascistische ambtenaren wisten dat de participatie van het gewone volk een hoogtepunt bereikte tijdens de toespraak die de Duce hield vanaf het balkon op Palazzo Venezia in Rome. Daarom was het primaire doel dat de pers dezelfde gemoedstoestand zou creëren als op dat moment.

Critica Fascista: Een (links)fascistisch tijdschrift

Critica Fascista was een tweewekelijks tijdschrift dat op 5 juni 1923, het eerste jaar van het Mussolini-regime, werd opgericht door een 28-jarige Bottai. In 1925 vermeldde het tijdschrift naast Bottai ook Gino Modigliani als oprichter, een Joodse koopman uit Milaan die de drukkosten voor zijn rekening nam. Het tijdschrift werd gepubliceerd tot 1943, het laatste jaar van Mussolini’s dictatuur. Het achttiende en laatste nummer verscheen op 15 juli 1943, enkele dagen voor de val van de fascistische regering. Bottai was gedurende de gehele bestaansduur van het tijdschrift redacteur en directeur. In zijn eigen woorden was het ontstaan van het tijdschrift “geïnspireerd door de drang om in actie te komen”. Het was bedoeld als tegenhanger van Critica Sociale, een in 1891 opgerichte links-socialistische krant die nog steeds verschijnt.

Critica Fascista was een uitgesproken politiek tijdschrift en was niet bedoeld voor een breder publiek. Er werden zelden meer dan 5.000 exemplaren gedrukt. Toch heeft het gedurende zijn twintigjarige bestaan aandacht besteed aan alle culturele aspecten van het fascistische regime. Er was ook ruimte voor samenwerking met onorthodoxe fascisten en mensen die de partij niet steunden. Het tijdschrift, met bijdragen van zowel interne als externe medewerkers, was daardoor als geheel van uitzonderlijk cultureel en sociaalpolitiek belang. Ondanks de beperkte oplage bleef Critica Fascista een zeer populair en invloedrijk tijdschrift.

Met de naam van het tijdschrift is iets bijzonders aan de hand: “critica” (kritiek) en “fascista” (fascistisch). Volgens Bottai, die terdege besefte dat veel mensen dit als een tegenstelling zagen, impliceert deze ongewone combinatie van “kritiek” en “fascistisch” dat de politieke veranderingen op de voet werden gevolgd en dat intellectuelen de ruimte kregen om te debatteren over de fascistische revolutie en deze te steunen. In de beginjaren van het tijdschrift was er de tendens om het fascisme te normaliseren en weerstand te bieden tegen provinciaals racisme. Bottai stond in deze periode nogal vijandig tegenover de onverzettelijkheid van het fascisme. In Critica Fascista keerde hij zich ook tegen de vijandige houding van het fascisme tegenover de buitenlandse literatuur. Zijn kritiek kwam voort uit een behoedzame en kritische houding tegenover de partij en haar leider, die begon toen Bottai lid werd van de Nationaal Fascistische Partij (PNF). Zijn ideeën voor de culturele sector hadden meestal weinig invloed. Niet omdat Bottai niet in de gunst stond bij Mussolini, maar omdat de initiatieven indruisten tegen de heersende fascistische ideeën en de uitvoering daarvan. Bottai streefde naar een ontwikkeld en verfijnd fascisme dat gebaseerd was op klassieke studies en dat open stond voor zowel Italiaanse als buitenlandse literatuur en politiek. Zijn opvatting over het fascisme was uiteindelijk hoofdzakelijk kritisch omdat hij pleitte voor een terugkeer naar het oorspronkelijke, “zuivere” fascisme. Hij vond namelijk dat de fascistische revolutie onvoltooid was, en mogelijk zelfs ondeugdelijk.

Het hoofdartikel van het tijdschrift werd, tenzij anders aangegeven, over het algemeen toegeschreven aan Bottai, hoewel het erop lijkt dat ook andere redacteuren aan de hoofdartikelen hebben bijgedragen. Bottai wordt vanaf 15 november 1926 niet meer vermeld als directeur-eigenaar van het tijdschrift omdat hij was benoemd tot staatssecretaris voor de corporaties.

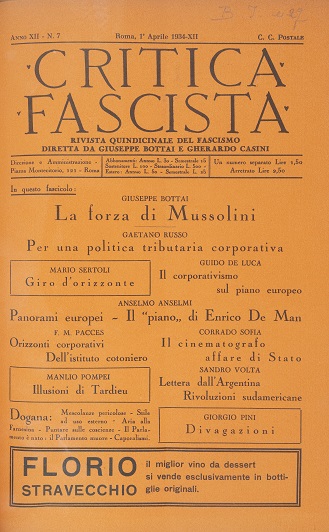

De collectie van Critica Fascista in de Bibliotheca Italiana is nog steeds eigendom van de Società Dante Alighieri , maar de Universiteitsbibliotheek Groningen heeft deze sinds de jaren vijftig van de vorige eeuw in bruikleen. De collectie beslaat slechts drie van de twintig jaar gedurende welke het tijdschrift verscheen: van 1 januari 1934 tot 1 januari 1937. De nummers 9 en 14-19 uit het jaar 1935 ontbreken echter. De voor- en achterkant van het tijdschrift, evenals de advertentiepagina’s zijn feloranje. De hoofdpagina's in elk nummer zijn wit. In deze periode waren betrokken bij het tijdschrift Giuseppe Bottai (directeur); Gherando Casini (tot november 1936 mededirecteur); Filippo Franceschi (vanaf 1936 hoofdredacteur); Nicola de Pirro (tot november 1936 hoofdredacteur); Giorgio Berlutti (manager), en Riccardo Ferrari (vanaf augustus 1926 hoofdadministrateur). Het drukwerk en de typografie waren in handen van Editrice Il Lavoro Fascista (vanaf 1933) en Tipografia del Senato del dott. G. Bardi (vanaf 1936).

De directie en de administratie van Critica Fascista was gevestigd op Piazza Montecitorio, 121, Rome. Giuseppe Bottai en Gherardo Casini werden vermeld als directeuren. Vanaf het eerste nummer van 1 november 1936 werd de eerstgenoemde niet meer vermeld, omdat hij geen mededirecteur meer was van het tijdschrift.

| Laatst gewijzigd: | 16 oktober 2024 12:20 |