Predicting acceptance of new (environmental) policies

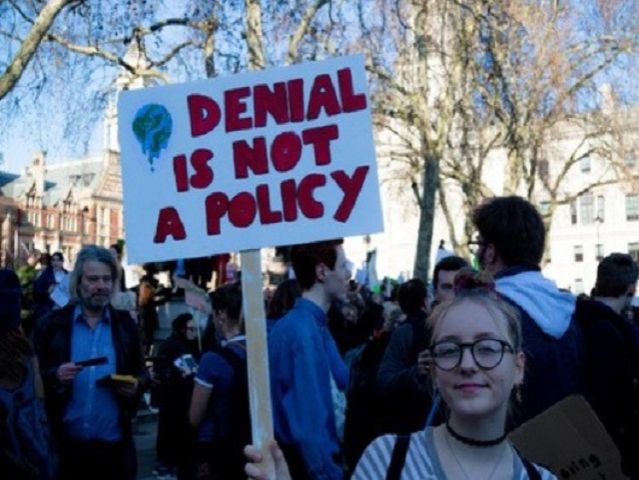

In our lives, privately or in our work context, acceptance or decline of change is omnipresent. Either when new policies affect us (new organizational policies, national laws) or when we ourselves want to stir change. However, in general, many people do not like change - it raises uncertainty, it costs time and energy, and it can be a monetary burden. So which factors contribute or hinder acceptance of policy/strategic change? Answering this question in the context of proposed strategic changes of an organization and the role boards play in this, is part of my research. Here, I discuss acceptance of policies with a best-practice example of an environmental policy, which shows three conditions of successful policy acceptance.

In Groningen, it is normal that the city center is almost car-free. The fact that people use their bikes instead, bears the advantage that there are no traffic jams in the center, less parking problems and – most important from an environmental aspect – fewer emissions. In other, larger cities car traffic is a problem though and therefore cities such as London and Stockholm aim to reduce car traffic. For this, they implemented car congestion charging schemes (in simple words: driving in the city center is expensive).

When first announced in Stockholm, public outrage was large.[1] This is because of a crucial process in people’s acceptance of a new policy: individuals’ evaluation of expected consequences. A study of the Stockholm intervention showed that people did not expect large improvements in traffic jams, emissions and parking problems, but were afraid of increased costs and crowded public traffic. After a trial period of seven month, the same people were asked again about their perception on actual consequences. It became visible that the negative consequences had been overestimated, while positive effects had been underestimated. [2] This is because, as often with environmental policies, the negative effects seemed certain and immediate and therefore are more powerful, while the positive effects are more uncertain and distant.[3]

The Stockholm congestion charge policy is a best-practice example because it also caters to the two other factors predicting policy acceptability. For one, the perceived fairness of the distribution of consequence. People can perceive fairness through three lenses: self-interested fairness (thought: “If I have to pay the congestion charge, I will be worse off financially”), fairness related to interests of others (thought: “everybody will be affected by the same rule, people who cause congestions and pollution problems will be affected more”) and fairness related to environmental impact (thought: “nature, the environment and future generations will be protected”). Because perceived fairness in the eye of the public was most strongly related to environmental justice and equality perceptions, this increased policy acceptance.[4]

The last reason for the high policy acceptance was the perceived fairness of the decision procedure. Stockholm first tried out the congestion charge during a seven-month trial period. Afterwards the citizens decided with a referendum whether the congestion charge should be continued. In the end, the people voted in favor of the congestion charge. It was permanently put into place in 2007 and Stockholm has successfully reduced the number of cars entering the charge zone by 22%.

Take-away: Acceptance of new policies or strategic plans - be it in our everyday lives, in the fight against global warming or in the boardroom - is linked to the expectation of consequences, the perceived fairness of consequence distribution and the perceived fairness of the decision procedure.

Julia Prömpeler (j.b.j.prompeler rug.nl) is a PhD candidate at the RUG Department of Human Resource Management and Organizational Behavior. She works with Prof. Dr. Floor Rink, Prof. Dr. Janka Stoker and Dr. Dennis Veltrop in the field of behavioral corporate governance, where she researches decision-making processes in the context of boards and Top management teams.

References:

1 - Isaksson, K. and Richardson, T. (2009). Building legitimacy for risky policies: the cost of avoiding conflict in Stockholm. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice 43: 251–257.

2 - Schuitema, G., Steg, L., and Forward, S. (2010a). Explaining differences in acceptability before and acceptance after the implementation of a congestion charge in Stockholm. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice 44: 99–109

3 - Geller, E.S., Winett, R.A., and Everett, P.B. (1982). Environmental Preservation: New Strategies for Behavior Change. New York, NY: Pergamon Press.

4 - Steg, L. E., Van Den Berg, A. E., & De Groot, J. I. (2013). Environmental psychology: An introduction. BPS Blackwell.