Micro-Level Spatial Justice: Public and Private in Harmony?

I am a Double Degree student who first came to Groningen in late summer 2024. The following lines share first personal reflections in connection to courses of the Master ‘Society, Sustainability and Planning’ that focuses on space and justice.

Observing the Neighbourhood: An Outsider’s Perspective

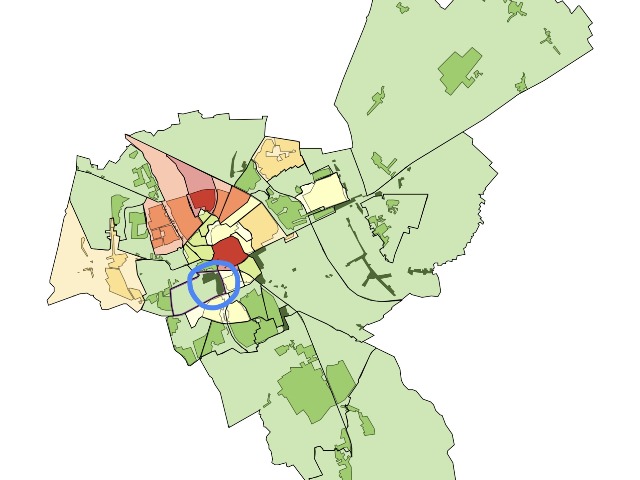

When I went to the street Droppingsveld (Grunobuurt) to conduct a field study on neighborhood safety for a group assignment in the course ‘City Matters: Urban Inequality and Social Justice’, my impression aligned well with the Groningen municipality assessment. The municipality had marked this neighborhood as a “green zone” on its official website, indicating high safety levels. And indeed, after visiting alone three times at different time periods during the day, I found the area to be incredibly peaceful and safe, even at night. The quiet, steady rhythm of the space made me so relieved and unafraid of staying there alone for a few hours. Therefore, I settled on a bench near the playground alongside the street of Droppingsveld to observe the physical environment (buildings, streets, and facilities), as well as the social environment, watching the people who came and went, their activities, and their interactions.

However, I realized my role as an observer made me question my place within the community. In a residential area with no commercial elements and low foot traffic, I might be perceived as the only unknown or even suspicious element on the street. Residents walked quickly and purposefully, whether alone or in pairs, clearly heading toward specific destinations—either home or the playground. People had little reason to wander or gaze around. If I would like to put myself in the residents’ shoes, I could find a stranger hanging around, unconnected to the community’s daily life, sitting on a bench and observing with seemingly no clear purpose.

It seems that my behavior was not that of a resident who is using their community space for a purpose. After considering this, I took a different approach on my second and third visits. I brought my laptop, pretending to work occasionally while observing the surroundings. I supposed this could help me appear more engaged and less “out of place”. But what did it tell me about the neighbourhood?

The Neighbourhood at a Glance

Droppingsveld sits in a residential area southwest of Groningen’s city center. This 100-meter street has a three-story residential building on one side and a grassy playground on the other. The playground has benches, fitness equipment, and children’s play equipment, and the street is straight and unobstructed, allowing one to see clearly from end to end. Vehicles park alongside the residential building, while tall trees stand on the playground side, giving the space an open feel without obstructing views.

The sense of visibility here contributes to my feeling of “intrusion”. With over two-thirds of the windows of the residential building left uncurtained during my three observations, the view outside is open to residents indoors. But on the other hand, for me, their activities at home were also clear in an open view. I found myself inadvertently catching glimpses of their indoor activities. The openness of the setting, which offers residents a clear view of the playground, creates a reciprocal visibility in which privacy becomes blurred, raising questions about where private space ends and public space begins. This made me think about spatial justice at the micro level. In this case, specifically, it refers to the justice of dividing private space from public space.

Micro-Level Spatial Justice: The Balance Between Openness and Privacy

Discussions of spatial justice often focus on the macro- and meso-level, for example, resource allocation across urban areas. However, micro-level spatial justice—the quality of space and its interaction with daily life—is equally essential. Spatial justice in public spaces extends beyond fair distribution; it involves ensuring spaces are safe, inclusive, affordable, and conducive to diverse, open environments. Just as Beveridge and Koch (2024) argue, urban spaces blur traditional boundaries between public and private, often causing social tension.

But what is this kind of justice from the perspective of residential design? As Boettger (2014) points out, 20th-century architects favored open layouts to create new connections between indoor and outdoor spaces. Walls gave way to free-standing panels and structural supports to organize spaces without fully enclosing them. However, this creates a paradox: how do we keep spaces open without first closing them off? And how can a building invite people to see inside while protecting its occupants’ privacy?

For urban residents, having outdoor social spaces that encourage interaction is vital to spatial justice at a micro level. Jan Gehl’s Life Between Buildings highlights that the physical structure of residential spaces should support the social framework necessary for community life both visually and functionally (Gehl, 2011). From this perspective, in Droppingsveld the building opposite the playground provides an ideal setup for community life. The playground offers space for sunlight, picnics, and conversations. Residents can observe playground activities from indoors, and if inspired they can also join in.

However, having open public spaces and private spaces that provide a foundation for social interaction is like the two sides of a coin here. Privacy is fundamentally a dialectical relationship between the private and public, where control over access by others depends on the boundary control of social space - the interface mediates power relations (Dovey & Wood, 2014). For residents, opening the curtains means that private activities are exposed to public view, while closing them means a potential reduction in social interaction and “eyes on the street” (Jacobs, 1961). Most of us agree that diverse social interactions are beneficial. But where does the public end, the private begin, and what is a suitable balance for balancing openness and privacy? What would we recognise as just?

Human Interaction and Space Practice: A Sense of Belonging

Urban life is essentially defined by spatial practices. Cities bring together diverse forces, consolidating spatial differences and motivating people to take ownership of urban spaces (Purcell, 2022). “Human space in the city should not only foster self-respect, reflecting moral equality and social belonging, but also self-esteem, valuing individuals’ contributions to society” (van Leeuwen, 2022). Henri Lefebvre’s classic work emphasizes that space embodies social relationships (Lefebvre, 1991).

Beveridge (2024) points out that collective political practices in cities require resources beyond power, capital, and social relationships, including cohesion, belonging, and shared aspirations. In the Droppingsveld case, we see that every-day social practices require such elements even more. In the long-term interactions between indoor and outdoor spaces, the playground on one side of the street is considered as part of the residential area, which leads to a higher level of oversight and collective responsibility for this public space (Gehl, 2011).

Jacobs’ “eyes on the street” concept has become deeply ingrained, referring that frequent interactions and constant gazes directed towards the street in a vibrant street environment can be viewed as a form of surveillance for street safety (Jacobs, 1961). This is exemplified perfectly in the Droppingsveld street that I observed. When I sat on the bench in the playground and observed my surroundings, I saw couples with children coming to play on the swings, two girls sitting on the grass having a picnic, a middle-aged man stopping to exercise on the playground on his way home, people hanging out on the balconies of residential buildings, and others hanging out their laundry or sitting and chatting. All these behaviors fell under the collective gaze of all these groups, forming a harmonious scene. I believe that my transition from sitting and visibly observing to sitting down with my computer to work has allowed me to better integrate into the harmony of this neighborhood - this is my spatial practice which I intend to get along with the residents’ spatial practice.

Harmony-based Spatial Justice: The Humanism Side

So, what do I see as the connection between harmony and spatial justice? The idea of micro-level spatial justice revolves around the everyday social interactions that occur within our shared urban spaces. Unlike the broader and more politicized struggle for “the right to the city,” which often focuses on democratic access and collective agency in urban decision-making, micro-level spatial justice is shaped by daily routines and unspoken agreements that people maintain in their local environments. These interactions help reinforce and adjust the boundaries between private and public spaces, creating a subtle yet essential framework that allows residents to coexist comfortably and securely.

At this level, spatial practices such as the inter-observation due to the visibility of indoor activities through uncovered windows may not typically represent expressions of political power. However, they play a vital role in maintaining social balance and informal regulation. It isn’t enforced by laws but rather by social norms and shared expectations. In well-functioning communities, this harmony based on mutual observation creates an inviting environment where individuals feel free to enjoy public spaces while being protected from unwanted intrusions.

Such harmony-based micro-level spatial justice is crucial for urban residents’ thriving since it supports community structures aligned with basic human needs for connection as well as privacy. It enables people to experience belongingness alongside respect for others, which fosters those often-overlooked small-scale social ties within larger urban policies. In the micro-level spatial practice, it empowers individuals to claim space not through political or legal means but based on a sense of belonging built over routine interactions. This sense of “ownership” is key to feeling integrated into the urban landscape; it encourages residents to care for shared spaces actively look out for each other while engaging collectively in maintaining both physical surroundings as well as social boundaries defining their neighborhood, which aligns with Lefebvre’s call for a “new humanism of urban society” (Dovey & Wood, 2014).

Practical Implications: How to Build a Harmonious Residential Environment?Turning back to Droppingsveld, my observations from the street prompted me towards insights for improving residential neighbourhood design to enhance micro-level spatial justice and community cohesion for the neighbourhood itself as well as other neighbourhoods.

-

Visibility without over-exposure. Maintaining open sightlines is essential for fostering safety and interaction. However, balancing this with privacy is also crucial. Thoughtful landscaping and architectural elements such as semi-transparent barriers or shrubs of appropriate height may provide a sense of enclosure without blocking visibility.

-

Encourage social interaction through amenities. Public spaces like playgrounds, fitness equipment, and seating areas can create opportunities for community engagement and thus building a sense of belonging.

-

Respect the balance between public and private. The distance between public spaces and buildings, the width of the street, the provision of greening, balconies, and window placements can subtly impact residents’ sense of privacy and connection to the outside world.

By balancing public openness with privacy, fostering social interactions, and encouraging collective responsibility, neighbourhoods can create environments where individuals feel secure, connected, and respected. The harmony is not just a goal of design, but a lived experience, sustained by daily practices of the residents. For urban planners, the challenge lies in creating spaces that respect these dynamics while encouraging the social cohesion that allows cities to thrive, where micro-level spatial justice plays an important role.

References

Beveridge, R., & Koch, P. (2024). Seeing democracy like a city. Dialogues in Urban Research, 2(2), 145-163.

Boettger, T. (2014). Threshold Spaces: Transitions in Architecture Analysis and Design Tools. Walter de Gruyter GmbH.

Dovey, K., & Wood, S. (2014). Public/private urban interfaces: type, adaptation, assemblage. Journal of Urbanism: International Research on Placemaking and Urban Sustainability, 8(1), 1–16.

Gehl, J. (2011). Life between buildings (6th ed.). Island Press.

Jacobs, J. (1961). The Death and Life of Great American Cities. New York: Random House.

Lefebvre, H. 1991[1974]. The Production of Space. New York: Blackwell.

Purcell, M. (2022). Theorising democratic space with and beyond Henri Lefebvre. Urban Studies, 59(15), 3041–3059.

Silver, C., Freestone, R., & Demazière, C. (Eds.). (2018). Dialogues in Urban and Regional Planning: Vol. 6. The Right to the City. Routledge.

van Leeuwen, B. (2022). What is the point of urban justice? Access to human space. Acta Politica, 57(1), 169–190.

Photo: Photo of Droppingsveld (Source: Author)

Map: Basismonitor Groningen (Source: https://basismonitor-groningen.nl/kompasvangroningen, accessed 17-01-2025)

This text has been crafted by Xuefei Zeng reflecting especially on student work in the course 'City Matters: Urban Inequality and Social Justice’ at the University of Groningen, Faculty of Spatial Sciences. It is based on an individual assignment. The course was taught by Christian Lamker, Sara Özogul, and Sander van Lanen, between September and November 2024 as a compulsory course for Master students in the programme Society, Sustainability and Planning (SSP), the connected Double Degree Programmes, and as an elective to other Master programmes of the Faculty and the University. Xuefei studies in the Double Degree Programme ‘Urban Planning within a Global Environment’ with Renmin University (China).