Beyond neoliberal housing in Amsterdam: a tale of tactics, tenure and territorialization

| Date: | 25 January 2023 |

| Author: | Bart Popken |

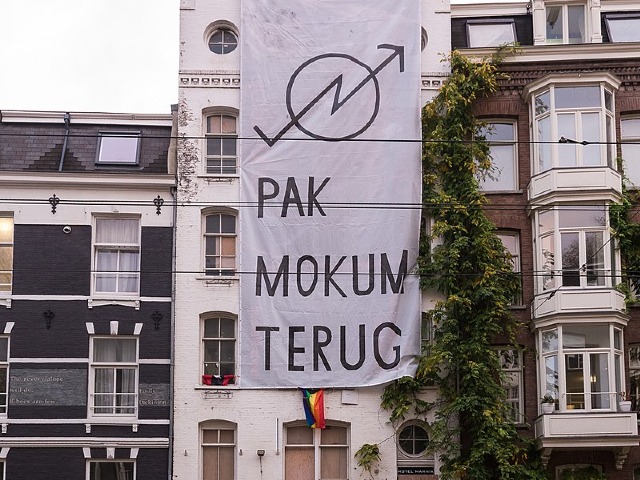

Squatting practices have become more fragmentized, strategic and hostile compared to the 1960s in the Netherlands. During the 60s, free spirited spaces in the form of vacant buildings were envisaged as opportunities for collective support and empowerment of lower social classes (Pruijt, 2014). However, due to the increasing scarcity of space and the pressure of commercial powers, the idealist notion of the 1960s is now pushed to the abyss by urban governments which increases tensions between squatters, private actors and urban governments. The increased political leeway for the development of neoliberal housing policies led to a recurrence of squatting movements giving rise to a neo-Provo culture in Amsterdam. In the year 2010, squatting became officially illegal in the Netherlands which made state authorities actively discourage and co-opt squatting practices (Pruijt, 2014). Moreover, state-led gentrification has conjoined the powers of private actors and the state resulting in an inequal institutional housing playfield. The forced evictions arising from gentrification trigger manifestations of discontent among squatters. Urban grassroot tactics of citizens, under the ideological notion of urban revanchism, aim to infiltrate the totality of urban systems via brief moments of release from the hegemonic power apparatuses (De Certeau, 1984; Miraftab, 2009; Mould, 2014). Hence, squatting practices are unique as they can carve out political spaces between co-option and autonomy and create ephemeral cracks in the urban system that engender possibilities for collaborative learning process, democracy and social justice (Verschelden et al., 2012). This blogpost will discuss how the squatting movement Pak Mokum Terug (PMT) uses tactics to create urban cracks in the urban system to reconfigure urban space in a non-profit driven way.

Dutch squatting: an urban strategy or tactic?

Where earlier grassroot movements were united on the basis of somewhat of the same revanchist ideology, the neoliberalization of cities shattered the unitary activist spirit resulting in a mosaic of tactical urbanist practices (Iveson, 2013). Squatting could be seen as one of these tactical urbanist practices as it mainly tries to employ tactics to reclaim urban space from neoliberal governments. These reclaimed urban spaces are defined as political openings or urban cracks (Mould, 2014; Verschelden et al., 2012). Urban cracks are deliberate spaces created by sidelined citizens to counteract political power imbalances in the city (Verschelden et al., 2012). Some authors conceptualize urban tactics as community oriented, small-scale initiatives conducted by citizens (Geertman, 2016; Lydon & Garcia, 2015). This everyday urbanism is driven by low-politics which entails the everyday life choices of citizens and refers to the political strategies of squatters, street vendors and other subcultures that slowly trigger social and urban transformation (Geertman, 2016). However, conceptualizing urban tactics as slow democratic processes completely cloaks the ephemeral and conflictual nature of tactics. I want to elaborate on squatting as a posterchild example of an ephemeral urban tactic.

There is much debate on how to define squatting practices in contemporary neoliberal cities. As squatting actively contests neoliberal hegemonic strategies, it can utilize political openings in the hegemonic system to employ counter-hegemonic acts. Their transgressive nature transcends national boundaries as they built transnational solidarities and are imaginative as they recover idealisms for a just society (Miraftab, 2009). What still remains ambiguous is to what extent contemporary squatting in the Netherlands should be seen as a truly counterhegemonic urban tactic (Mould, 2014) or rather a form of everyday urbanism driven by strategies of low politics (Geertman, 2016). Hence, there is a need for conceptual clarification between strategies and tactics. De Certeau (1984) stresses that strategies assume that places can be circumscribed and can be seen as delimited as its own. Conversely, tactics aim to create bottom-up change by infiltrating the totality from within but never claim the conquered territory as its own (Mould, 2014). In other words, whereas strategies could be seen as representational spectacles of being, tactics are rather opaque and fluid spectacles of becoming (Kunimoto, 2019).

De Certeau (1984) tries to avoid the distinction between tactics and strategies. He addresses that tactics capitalize on advantages and manipulate strategies to turn them into opportunities. Opportunities in this sense refer to the destabilization of the neoliberal order to provide non-capitalist alternatives to the dominant spatial strategies within the city (Purcell, 2002). The conquered urban space of squatters can temporarily reappropriate a place, however on the long run the reclaimed urban space gets moulded back into the neoliberal territorial system (Mould, 2014). Subsequently, tactics cease to become ephemeral and become part of a city her strategy and politics. The latter is defined by Mould (2014) by using Deleuze & Guatarri their analogy of lines of flight (tactics) in the apparatus of capture (urban governments). Lines of flight emerge when our desire produces new modes of existence that can resist the dominant political apparatus in the city. A case study of the Amsterdam squatting movement PMT will shed light on how Dutch squatting movements employ lines of flight to manipulate the neoliberal everyday business and turn them into opportunities.

Pak Mokum Terug!

Hotel Marnix was established in the year 2008 by two brothers coming from the wealthy neighbourhood Amsterdam Nieuw-West. Ten years later the hotel was closed because of renovation, leaving the hotel to become vacant. Shortly thereafter, various squatter groups occupied the vacant building for short periods of time. On the 13th of October in 2021, a group of young activists occupied hotel Marnix. They called themselves, guided by an urban revanchist spirit, Pak Mokum Terug (Get Mokum Back). ‘Mokum’ is how the local citizens of Amsterdam have started nicknaming the hotel over time. Both owners of the hotel were annoyed by the squatting activities in their property and stressed that the squatters had to leave the vacant hotel immediately. They consulted the municipality of Amsterdam to pressure the squatters and make them leave. This led the municipality to develop an eviction strategy. They justified this strategy by stating that the fire safety standards in the building were far below standard and that because of mistakes within the construction design the building was prone to collapse. Therefore, renovating the building would take too long and thus the building had to be immediately cleared (Hielkema, 2021). The mayor of Amsterdam Femke Halsema stated that she places all her trust in the research of the local fire department and immediately approved the eviction. The squatters accused Halsema of making hasty conclusions with lack of substantiation and didn’t show any goodwill for cooperation. One of the leaders of the squatting movement elaborated on his experience with the municipality:

“While there are negotiations with the municipality, we feel that these meetings are misused for the sake of evicting us. The decline in trust between the citizens and the municipality will only increase as a consequence of this. Because of this decision, many of the current Mokum residents will be booted.” (NOS, 2021).

When the municipality teamed up with the property owners, the squatters immediately started to put their heads together aiming to fight the eviction procedure. On Friday 26th of November they filed summary proceedings against the decision of the municipality. All the effort was of no avail as the judge picked the side of the municipality and the property owners leaving the squatters with empty hands. However, the squatters did not go down without a fight.

Lines of flight

Before the actual eviction took place, there were many signs of solidarity from squatting movements all over Amsterdam. On Friday 26th of November, the evening before the actual eviction took place, Pak Mokum Terug organized a demonstration at the Leidseplein in Amsterdam. Approximately 150 people showed up and there were performances of the progressive artist Sophie Straat and punk band Hang Youth. The protest ended with a collective and peaceful march towards the town hall of Amsterdam. One day later, tension could be felt all over the city of Amsterdam and just before the eviction was planned to begin something peculiar happened. At the beginning of the afternoon, a 1994 Renault Twingo had been parked before the entrance of Hotel Mokum with the spray-paint ‘Fuck Capitalism’ (Parool, 2021). Shortly after, several squatters arrived and collectively clung themselves to the Twingo by using lock-ons.

Meanwhile, the government forces failed to show up on time and people started to wonder if the resistance tactics of the squatters weren’t wasted energy after all. However, after an hour, police forces started to show up and shouted through a loud megaphone that the squatters had to move the car. No hearing. Subsequently, local mayor Femke Halsema had been called in to reprimand the squatters. This worked counterproductively as the squatters collectively answered by singing: “Not Green, Not Leftist, Not Neoliberal” as an attack on the political inconsistency of Halsema. After the arrival of the ME, a group of mobile police units surrounded the Twingo. After some time, the police came to an agreement with the squatters as they proposed to evict them peacefully. Notwithstanding, the police did not hold themselves up to their end of the bargain and evicted 9 squatters of the Pak Mokum Terug squatting movement with brutal force (NOS, 2021). Several of them got arrested and threatened with court cases. Half a year later, the squatters movement started an international fundraiser to support the arrested people by covering for their juridical costs (Squat!Net, 2022).

A city for whom actually?

Whereas the municipality of Amsterdam envisages squatting as an illegal act that needs to be discouraged and punished, squatters themselves see squatting as a solution. Pak Mokum Terug emphasize that squatting is a solution to the current housing crisis and the commercialization of the city of Amsterdam. Increased deregulation as part of wider neoliberalization of housing has transformed the city into a playground for landlords (Van Gent & Hochstenbach, 2020). There are barely any regulatory mechanisms installed by the municipality which exacerbates socio-spatial inequalities. One of the squatters of PMT poses the following question in an interview with AT5:

“Are we a city for artists and teachers or are we a city for people that can only afford insanely high rents?” (AT5, 2021).

This captures the contemporary discussion of the right to the city. The rent increases in the city of Amsterdam have increasingly spiraled out of control, making the urban center a space for the affluent and displacing the sidelined residents. The subsequent liberal appropriation transforms the aura of the inner city into a hyperreal capitalist spectacle aiming to feed the tourist and yuppy gazes. The loss of the historic urban identity weighs heavily on the native residents who experience urban change at rates beyond their comprehension. Therefore, the question asked by the squatter not only symbolizes a wider spatial question of who possesses the right to urban space but also how the urban identity transforms as a consequence of this.

Squatting as a temporary solution

The case of Hotel Mokum shows how far squatters can go in fighting against commercialization to create more social justice in the city of Amsterdam. It is highly doubtful that squatting tactics are effective in reclaiming urban spaces for the long-term in the Netherlands. However, this specific squatting event has proved to be effective in the short-term destabilization of the neoliberal ‘everyday business’. It comprised both urban strategies and tactics that have been enacted to combat the strong forces of neoliberalism dominating the housing market in Amsterdam. At the same time, the event symbolized a rather general political cry for a community-oriented and just reconfiguration of the planning system. The peaceful demonstration showed that acts of resistance driven by low politics do not have to include violence or conflict. However, this blogpost has tried to redirect attention from low politics driven strategies to radical urban tactics. In my opinion, urban tactics are unique as their ephemeral nature makes them less prone to become subverted by urban governments compared to strategies that rely on the politics of the status quo. Urban tactics therefore have the potential to manipulate hegemonic urban strategies and turn them into temporary opportunities for sidelined citizens.

The lock-ons on the Renault Twingo could be envisaged as an urban tactic operating within the wider squatting event of that day. This symbolizes a spark of creativity resulting from a brief moment of release from the apparatus of capture. It succeeded in effectively manipulating strategies by hindering police agents from starting the actual eviction procedure. Despite the seemingly innocence of this act, it symbolizes a window of opportunity. It shows that urban tactics can effectively infiltrate and destabilize neoliberal urban strategies and spread awareness concerning capitalist injustices. It are these lines of flight in the apparatus of capture that temporarily melt the frozen realities imposed upon us by the logic of neoliberal everyday business. What could be seen in the case of Amsterdam is that with contemporary urbanisms, urban tactics and strategies tend to get subsumed by urban governments. As neoliberalism thrives on pacifism, all the chaos and disorder in the city needs to be systematically repressed. Subsequently, the reclaimed cityscape by PMT has been molded back into the urban neoliberal system of Amsterdam. Therefore, contemporary tactical urbanist projects turn into empty signifiers as they becomes merely a political tool to engender neoliberal development rather than empowering the actually sidelined groups in society. Instead of suppressing and co-opting urban tactics, it would be way more valuable to envisage them as creative ‘thought projects’ which function as laboratories of experimentation that create new visions of future urban living.

This text has been crafted by Bart Popken, student in the Research Master Spatial Sciences (ReMa) as part of the course 'City Matters: Urban Inequality and Social Justice' at the University of Groningen, Faculty of Spatial Sciences. The course was taught by Christian Lamker, Sara Özogul, and Sander van Lanen, between September and November 2022 as a compulsory course for Master students in the programme Society, Sustainability and Planning (SSP) and as an elective to other Master programmes of the Faculty and the University.

"This blog post is published under creative commons, CC-BY-SA International 4.0 license"

Bibliography

AT5 (2021). Krakers moeten “Hotel Mokum” uit: politie gaat pand ontruimen. AT5. https://www.at5.nl/artikelen/212147/krakers-moeten-hotel-mokum-uit-politie-gaat-pand-ontruimen

De Certeau, M. (1984). The practice of everyday life. London: University of California Press.

Deslandes, A. (2013). Exemplary amateurism: Thoughts on DIY urbanism. Cultural Studies Review, 19(1), 216-227.

Geertman, S. (2016). Tactical Urbanism: The Impact of Art Going Public in Hanoi. In 5th International Conference on Vietnamese Studies, Hanoi, Vietnam, December (pp. 15-18).

Hielkema, D. (2021). Halsema: Kraakpand Hotel Mokum was ‘buitengewoon onveilig’. Het Parool. https://www.parool.nl/amsterdam/halsema-kraakpand-hotel-mokum-was-buitengewoon-onveilig~b79c40af/

Iveson, K. (2013). Cities within the city: Do‐it‐yourself urbanism and the right to the city. International journal of urban and regional research, 37(3), 941-956.

Kunimoto, N. (2019). Tactics and Strategies: Chen Qiulin and the Production of Urban Space. Art Journal, 78(2), 28-47.

Lydon, M., & Garcia, A. (2015). A tactical urbanism how-to. In Tactical urbanism (pp. 171-208). Island Press, Washington, DC.

Miraftab, F. (2009). Insurgent planning: Situating radical planning in the global south. Planning theory, 8(1), 32-50.

Mould, O. (2014). Tactical urbanism: The new vernacular of the creative city. Geography compass, 8(8), 529-539.

NOS. (2021). Grote ontruiming kraakpand Amsterdam, negen aanhoudingen. NOS.nl. Geraadpleegd op 13 september 2022, van https://nos.nl/artikel/2407302-grote-ontruiming-kraakpand-amsterdam-negen-aanhoudingen

Pruijt, H. (2014). The Power of the Magic Key. Scalability of squatting in the Netherlands and the US.

Purcell, M. (2002). Excavating Lefebvre: The right to the city and its urban politics of the inhabitant. GeoJournal, 58(2), 99-108.

Squat!net. (2022). Amsterdam: Mokum Kraakt start inzamelingsactie voor arrestanten ontruiming Hotel Mokum! https://nl.squat.net/

Van Gent, W., & Hochstenbach, C. (2020). The neo-liberal politics and socio-spatial implications of Dutch post-crisis social housing policies. International Journal of Housing Policy, 20(1), 156-172.