Preserving the web for researchers of the future

How do you archive the internet? What are you going to keep and what are you not going to keep? And who decides this? These are questions that Susan Aasman thinks about on a daily basis. The media historian and Professor of Digital Humanities at the UG is a strong advocate of preserving the digital cultural heritage. ‘Eighty percent of the history of the internet is already gone.’

By: Lieke van den Krommenacker / Photos: Henk Veenstra

Imagine it is 2074 and you would like to know how the ideas of right-wing political parties became popular in the Netherlands at the start of this millennium. Internet fora and social media channels, such as Facebook and X—formerly Twitter—will then be important sources. But do they still exist? And if they do, is what you are looking for still easily findable and accessible?

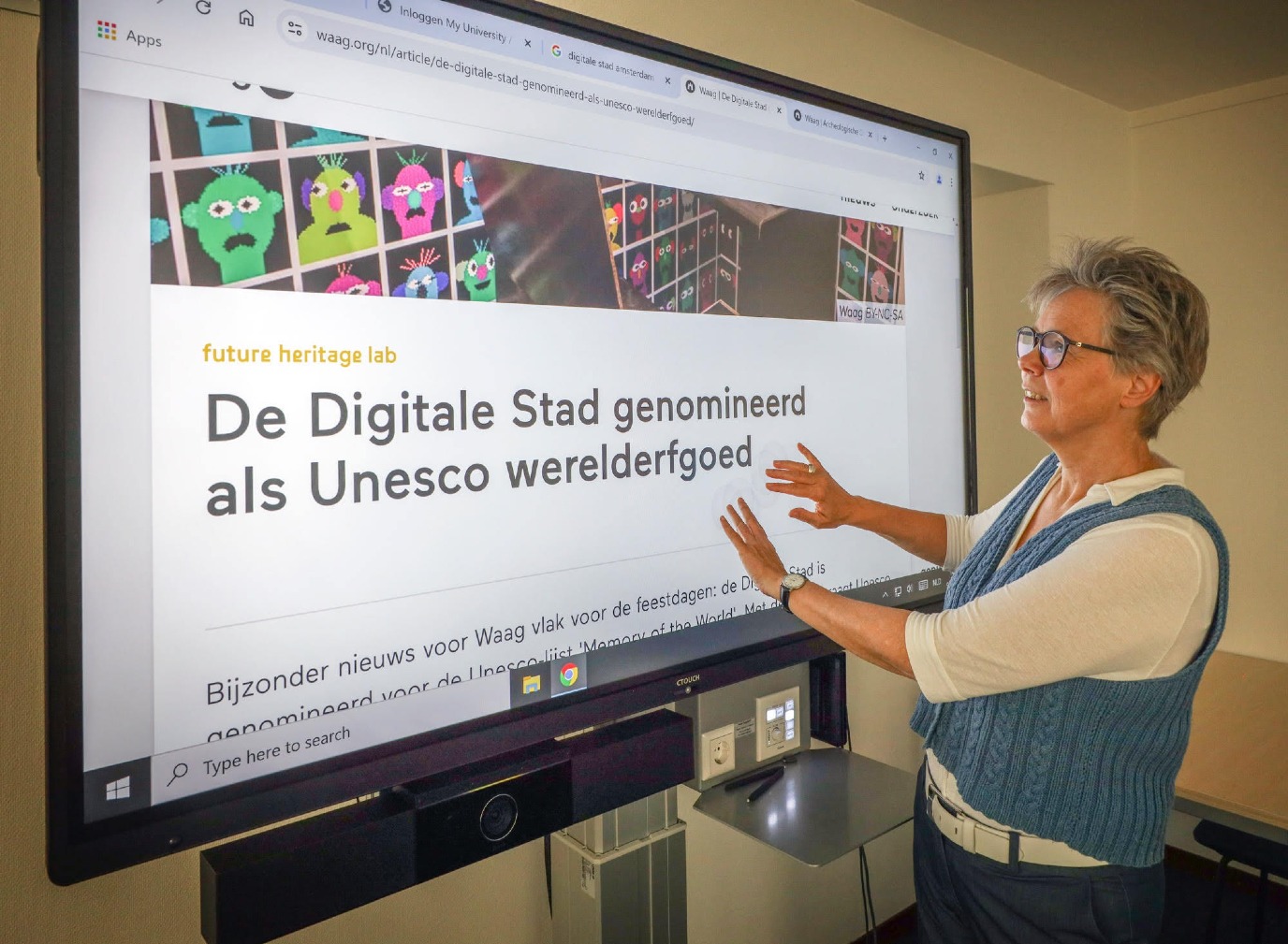

Media historian and Professor of Digital Humanities Susan Aasman of the UG focuses on these and other issues. ‘I’m really interested in the history of the web,’ she says in her office on the third floor of the Faculty of Arts in Groningen. ‘It has become my mission to advocate for the preservation of the digital cultural heritage. The question is, what are you going to keep and what are you not going to keep? And who decides this? These questions always pop up when archiving material; the difference here is that we live in a time where we could say: we’re keeping everything.’

Choices

For numerous practical and ideological reasons, keeping everything is not possible. For example, to store large amounts of digital data you would need countless data centres, which take up space. A lot of space. Besides, just like photos and written documents, data should also be kept under the right climatological circumstances. And speaking of the climate: the required data centres, which require large amounts of scarce resources, use enormous amounts of electricity as well. Aasman: ‘Given the climate crisis we’re in, you could wonder if we should even want to do this, keeping all of these data.’

The professor remembers a conference where one of the participants, a technician, argued: we can keep everything, so we should keep everything. ‘But,’ Aasman disputes, ‘storing is only one component of what archiving comprises. If you want to archive properly, you would also add metadata, such as a year, keywords, and where exactly something can be found. And do you only want to store the website or also the underlying HTML code?’ In short, it takes a lot of time and energy to properly maintain an archive. ‘This means you have to weigh everything up, which is quite tricky because it is likely that in fifty years someone will say: you made exactly the wrong choices.’

Web archaeology

Think about the current debate about our colonial history, says Aasman. ‘Now, it turns out that we never worried about various aspects of history in that time, aspects that we now see as hugely problematic, but little to nothing of those aspects has been preserved. As a result, a lot of digging needs to be done to make things rise to the surface.’

This applies to analogous sources just as well, of course, Aasman emphasizes. Photos, books, and papers can be lost in all sorts of ways as well. ‘When I retire in an x number of years and nobody wants to have my books, I will throw them out. Unless I become a famous Nobel Prize scholar before that time. Then, they would suddenly become interesting again, right? Here’s the thing: storing data about events happening now is one thing, but retrieving information from earlier periods, something I call web archaeology, is a lot more complicated. It would be good to see if a method can be developed for that.’

XS4ALL

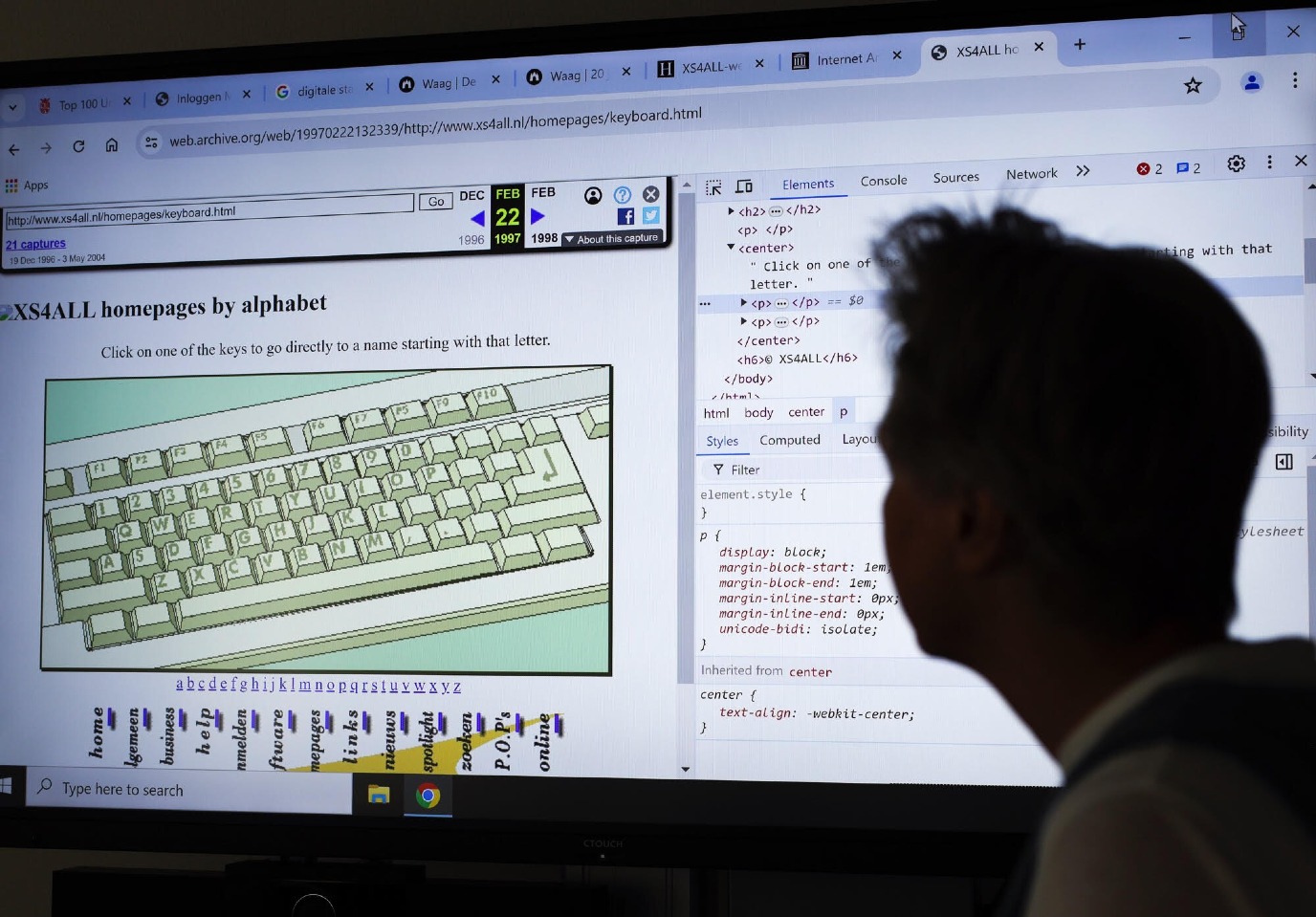

A special project that Aasman is working on with her PhD student Nathalie Fridzema is analysing a collection of homepages built by internet pioneer XS4ALL, one of the first Dutch internet providers. On 1 January 2019, the news broke that this provider—including ‘their’ thousands of websites and therefore potentially valuable digital cultural heritage—was going to disappear. So, the National Library of the Netherlands came up with the idea of a rescue mission: archiving as many homepages as possible. The organization came to Aasman for help and the initiative led to storing 3,000 early Dutch websites, including 413 ‘masterpieces’, such as the homepage of user Ranx who built the very first XS4ALL site in June 1994 with XS4ALL as host.

Aasman, who received her PhD for the significance of home movies as carriers of personal memories, set to work on the project brimming with enthusiasm. ‘This is what awakened my interest in the online recording of memories,’ she says. ‘I saw people posting their personal photos, home address, and phone number online. That was the moment I started thinking: who’s actually focusing on our web history? And how do we ensure that future historians can also look back to this day and age?’

Online Alexandria

The answers to these questions are versatile and complex. While a project like the XS4ALL archive is still relatively manageable, similar quandaries at the international level involve a lot more complexity. For example, European guidelines for storing digital heritage differ from country to country. Aasman: ‘In the United Kingdom, the entire web is ‘scraped’ once every two or three years. This entails that all the information on websites ending in .uk is downloaded and stored in a web archive.’ In America, they have the Internet Archive, a colossal online library inspired by the Library of Alexandria—the centre of knowledge in classical antiquity. Its goal is to archive the internet and make it accessible to everyone.

‘It’s not a public institute but a private company that was set up by a rich internet pioneer in the mid-90s,’ says Aasman. ‘To this day, he scrapes the web at random. In the Netherlands, this is illegal. The law doesn’t allow you to randomly scrape a website or social media.’ Last year, Aasman and one of the board members of the National Library pleaded in newspaper de Volkskrant for a legislative amendment that would change this. Their statement: The Netherlands neglects its internet history.

Trump tweets

Aasman: ‘You could say that 80% of the history of the internet is already gone. The moment you refresh a website, the previous version is gone. With platforms such as TikTok or Instagram, content often disappears even faster. The question is, of course: how bad is that?’

It all depends. Eternal access to all messages on popular online platforms such as the late Hyves or Twitter seems an unnecessary luxury, but the fact that someone in America saved the most sensational tweets by Donald Trump—many of which he deleted himself—and published them in a book might come in handy. The same goes for what has been said and written online about, for example, the childcare benefit scandal or the earthquake issues in Groningen. And while the average Instagram story might not at all be worth storing, things change when you want to know how ‘the average citizen’ experienced the coronavirus pandemic—something Aasman sees a lot of value in.

Sitting at home videos

‘At the time, they did choose to store important government communications, such as rules and prevention measures. But there’s also a lot that hasn’t been archived. During that time, I was also curious how people dealt with sitting at home, how they related to one another. So I downloaded TikTok on my phone.’ Aasman was able to see exactly what the effect was of the fact that the whole world went through the same thing at the same time. ‘People everywhere started making videos at home to drive out the boredom, to keep their spirits up. Highly fascinating. But when I started investigating who actually stores online contributions like this, the answer was: no one. Because it was an international phenomenon, no archive exists for it, and who would then be in charge? Examples like these confirm that we have a lot of figuring out to do together.’

More information

More news

-

14 February 2026

Tumor gone, but where are the words?

-

19 January 2026

Digitization can leave disadvantaged citizens in the lurch