When is a Psychic or a Witch a Fraud?

| Date: | 03 December 2018 |

| Author: | Susannah Crockford |

Reflections on Religious Fraud Investigations in North America

Does witchcraft, fortune-telling, or psychic healing constitute fraud, and (when) should the law step in to regulate these practices? Drawing on fieldwork with psychics in Sedona, Arizona, Dr Susannah Crockford considers recent witchcraft cases in Canada and the United States to argue against the framing of certain religious practice as inherently fraudulent.

The news that Toronto police have charged a Canadian woman, Samantha Stevenson, with pretending to practice witchcraft may be met with skepticism or derision in some quarters. After all, isn’t all such “superstition” inherently fraudulent? Stevenson convinced a 67 year old man that he was cursed by evil spirits, and that she could rid him of them – for a fee, of course. She ultimately took C$600,000 (approximately €400,000) from the elderly man. Canada’s criminal code allows for individuals to be charged with a witchcraft-related offense when they “fraudulently portray themselves as having fortune-telling abilities or pretend to use witchcraft, sorcery, enchantment or conjuration in order to obtain money or valuables from a victim.” According to the police force’s press release, “This charge is not connected in any way to any religion.”

This is not an isolated case. Another woman was recently charged under same law in Milton, Ontario, after defrauding a client of more than C$60,000. In Toronto, charges have also been brought for a woman posingas a witch and defrauding a man of over C$100,000, and a man who claimedto be able to lift a family’s curse for C$14,000.

Fraud cases of this kind also occur in the US. “Psychic Zoe” in New York City was charged with defrauding clients of $800,000. The “Greenwich Psychic” was arrested for identity theft and forgery in Manhattan, after defrauding a woman of $32,900. In another case, French psychic Maria Duval was the subject of a two-year investigation by CNN that uncovered that she, along with her business partners, scammed around 1.4 million Americans out of more than $200 million. Her mail fraud scam asked clients to pay $40 a pop for lucky numbers, guidance, and talismans for 20 years. There is even enough work in this area to support a private investigator who specializes in cases of psychic fraud.

The provision against witchcraft and fortune telling is soon to be rendered obsolete in Canada’s criminal code. The text of the law states that it applies to “Every one who pretends to exercise or to use any kind of witchcraft, sorcery, enchantment or conjuration; undertakes, for a consideration, to tell fortunes; or pretends from his skill in or knowledge of an occult or crafty science to discover where or in what manner anything that is supposed to have been stolen or lost may be found.” A viable defense is that the accused really believes they have such powers, or they accused can pay restitutionto the victim(s).

The law in the US varies from state to state. In New York, fortune telling is a crime (a misdemeanor) carrying the penalties of both 3 months in jail and a $500 fine. Those who are telling fortunes for amusement or as part of a show are exempt. The law states that: “A person is guilty of fortune telling when, for a fee or compensation which he directly or indirectly solicits or receives, he claims or pretends to tell fortunes, or holds himself out as being able, by claimed or pretended use of occult powers, to answer questions or give advice on personal matters or to exorcise, influence or affect evil spirits or curses.” All of New York’s psychics are breaking the law, although in practice they are rarely prosecuted for it.

Is this just modern day witch burning? Critics argue that these laws unfairly single out a particular religious practice. One study found that in Canada it was used disproportionately against women and minorities. The laws are unevenly applied, with storefront psychics allowed to practice and advertise as long as they do not cross a fuzzy line between charging for their services and not charging too much.

Such laws conflate witches and psychics and other occult practices. Psychics and witches are not the same, and are often offended by the implication that they are. Many witches follow Wicca, an officially recognised religion in Canada and the US, and some groups have been given tax exempt status. There is a long-standing tradition that Wiccans should not charge for their rituals. Many Wiccans follow a prohibition against doing harm to others, which would include defrauding them. From the perspective of mainstream Wicca, then, those that are charged under the laws against pretending to practice witchcraft are indeed not “legitimate” witches.

In the cases prosecuted under religious fraud laws, defendants are often accused of taking advantage of vulnerable people, telling them something bad will happen unless they pay. In most cases, this resembles a “secular” con: suggest a problem, project it onto a vulnerable person, then offer a solution for a fee. This makes it appear to be about marketing as much as religion, and this seems to be the attitude of police when declaring that such prosecutions are not connected to any particular religion. They would argue that these laws are intended to protect people from fraud, and are therefore not really about witches or psychics as such. But if there are already laws against fraud that would cover these cases, why maintain separate laws specifically singling out witches and psychics?

Further questions remain. What is the line between a fraudulent psychic or witch and a real psychic or witch? Who is qualified to judge? How is this different from other religious traditions in which services offering miraculous results are paid for, such as faith healing or seed churches?

During my ethnographic fieldwork on new age spirituality in Sedona, Arizona, I met many psychics and a few witches. As a well-known spiritual center complete with “vortexes” and special energy, Sedona is home to many different types of spiritual practitioners. The shopping district of Uptown has a number of storefront psychics, many offering readings for a fee. As with Wicca, there was discussion among psychics over whether it was appropriate to charge for services. Those who charged a fee (and were successful in doing so) often attracted the most criticism.

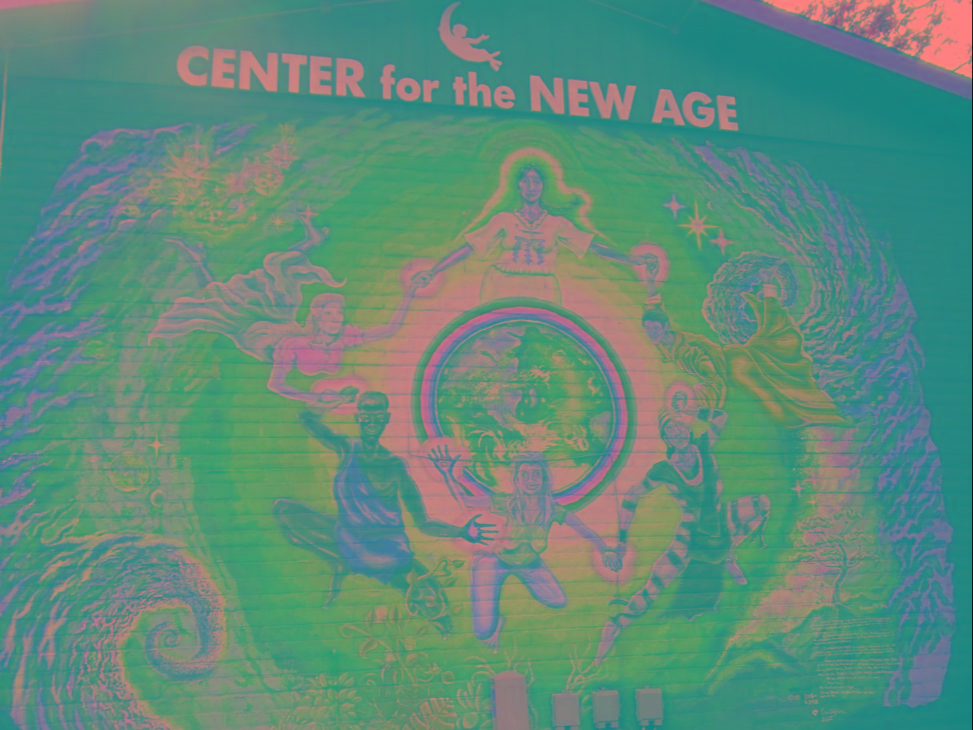

A successful and relatively long-lived commercial venture in Sedona was the Center for the New Age. It sat in a central location, attracting traffic from among the millions of tourists that visit Sedona every year. The lower floor was retail: books; Buddha statues; oracle and tarot cards; multitudes of crystals; prayer flags; all the usual material culture of spirituality was available for purchase. On the top floor was a series of rooms that different practitioners hired. Their pictures and cards listing their specialties were on the wall as customers entered the front door. A concierge on the lower floor would call up when a customer wanted to make an appointment and, if the practitioner was available, send them up for their reading.

My first host in Sedona, Vixen du Lac, told me that she worked at the Center for the New Age for 7 months when she first arrived. She was able to make around $4000 a week apparently. But she didn’t like it, characterizing it as a “psychic whorehouse.” The readers were subcontractors who paid the owner $1500 per month to rent one of the upstairs rooms (more if they took credit card payments through the store’s system). They had to make enough from clients to pay the rent as well as their own living expenses. They could not talk directly to the clients or book their own readings. The concierge would call up to them and send people up after choosing a face and name from the pictures downstairs.

Vixen made her room beautiful and did not charge for the introduction, so people stayed longer with her than with other readers, she told me, who just tried to “get them in the chair.” There was a bad atmosphere. She described the other readers as “catty,” like “Harry Potter’s Slytherin.” She qualified that they weren’t bad people; they were just misguided. It was too commercial, and that made it a bad place. It was all about the money.

Fortune telling, witchcraft, and psychic readings are not against the law in Arizona, except in one suburb of Phoenix. Even though it was not legally a form of fraud, there were many in the town who expressed misgivings about those who took money for readings, as Vixen did. There were even more misgivings about those who did so successfully, whose practice seemed less like ritual and more like commerce. The Center for the New Age was the most prominent commercial venture in town, and my informants often accused it of “selling spirituality.”

Those that worked there for long periods, however, took a different view. I was able to interview Scottie Littlestar, a psychic and medium who worked at the Center for the New Age for almost 17 years, in autumn 2012. I contacted her by email after seeing her postings on one of the Sedona spiritual community’s email lists. With dyed red hair, and wearing lots of purple, she sat in a chair and consulted clients through her Bluetooth earpiece. She allowed me to listen in on the preparatory talk she gave a client prior to a phone reading, so that I could learn how she did readings.

Scottie called herself an open channel for spirit. Clients could ask about anything – their past, present, future, or people who had already crossed over. The information came from what she called spirit, which she also named “Father-Mother-All that is”. While all topics were appropriate, she emphasized that she was not a fortune teller. What she did was not for entertainment purposes. Clients asked questions to help with their current problems, then she contacted their guides – beings in other dimensions that could see their past and their future. She said clients needed to be specific and not ask “general fortune teller stuff” where there were too many variables to be accurate.

She worked through feeling the client’s energy. This meant she could tell if they were a crook or shyster or someone without good intentions. Interestingly, she positioned herself as the one who could detect fraud.

Energy was the key to how psychic readings worked. Using their name and the town they lived in, Scottie said she could hone in on someone’s energy and locate them on a different dimensional level. Through a person’s energy she could tell where the best place for them to live would be, then look into their future and see if that move was going to go well. She went down that path as if she were them, asking clients to phrase questions as “if I do this, what is the outcome?” The information retrieved could heal, and she claimed that instant cures in her office had occurred in the past. She could also go to other dimensions and communicate with anything with life consciousness, including angels, fairies, aliens, and dead people.

Scottie charged for her readings. 15 minutes, with 3-4 questions, was $45, or $3 per minute. 20 minutes, with 5-6 questions was $60. 30 minutes, with 10 questions was $80, or $2 per minute. For $12 extra she provided a recording on CD. She did not drag it out on purpose to get more money. Prior to a reading, she took a client’s credit card and ran it through her machine, saying to me that she could rescind the payment on the same day if there was a problem. This was her offer to the client as well, if they were not happy for some reason, for example, if she ran short or long, they could get their payment returned. She made it clear that she was not going to take their money and proverbially run.

In Sedona, some psychics wanted payment. Others did readings by donation, asking only whatever offering a client could afford or wanted to give. Some only worked from their homes or over the phone or online (they did not want a storefront or to be known as a “Sedona New Age psychic”).

The idea that psychic readers can be prosecuted for fraud is entertained only when a payment is made. The premise of a psychic reading is dismissed as fraud to the extent that the prosecution is made not against psychics or witches for claiming that they can perform certain feats, as it once was, but when a payment is made to such an amount that it severely drains the victim’s finances. Most people can shrug off $40 easier than $40,000. It is only those who face significant financial loses who seek restitution, and then with some reluctance. Often psychic fraud cases go unreported because the victim is too embarrassed to report it. The financial cost of going to a psychic needs to surpass the social cost of admitting that they paid to see a psychic in the first place.

If cases were handled under general fraud laws, it would reduce the embarrassment and stress for victims of trying to make an accusation against a “pretend” witch or psychic. It would also no longer maintain a separate category of fraud covering occult practices which is archaic and unnecessary in the contemporary era, and furthermore singles out a particular form of religious practice as inherently fraudulent.

Dr Susannah Crockford is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow in the Department of Literary Studies, Ghent University.