West, East, and Bureaucratic Torture

Next Tuesday 23.2.2016, at 11:00-13:00 Prof. Smadar Lavie will give a lecture in Groningen as part of a tour promoting her book “Wrapped in the Flag of Israel” – Mizrahi Single Mothers and Bureaucratic Torture. The lecture will take place in the Zittingszaal, Faculty of Theology and Religious Studies, Oude Boteringestraat 38, Groningen. In today’s post, Ronit Nikolsky provides a brief overview of the content of Prof. Lavie’s book and the questions and issues she will explore further during this lecture.

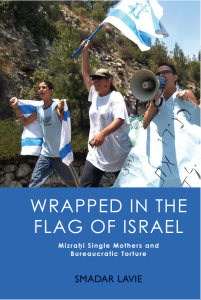

A surprising title. One expects a book titled “Wrapped in the Flag of Israel” to be about a radical Zionist movement, and if so, what do single mothers have to do with it, and what is mizrahi? And while we’re at it, what does bureaucratic torture mean?

Well, the book is not about a radical Zionism in any way; quite the opposite.

“Wrapped in the flag of Israel” refers to an event which took place in 2003, in which Vikki Knafo, a single mother, a Mizrahi (that is, a Jew of Middle Eastern origin), marched from the periphery, (referring to the transition town, typically a government arranged dwelling area in the less developed areas of the country, to which the newly arriving immigrants from Muslim countries were directed), to the capital Jerusalem wrapped in the flag of Israel, in order to protest against state bureaucracy which had been torturing her for year, by making unrealistic demands from her as a weakened Mizrahi single woman from the periphery.

Knafo’s one-person protest grew as she neared Jerusalem, when more and more people joined her in the long march.

The case of Mizrahi single mother’s activism highlights the complexity of Israeli society, and throws new light on the issues that are also discussed in Europe, namely the encounter between European ideologies and sensibilities, informed by mainly Christian and secularist heritage, and Middle Eastern ones, shaped in part by Islam. This encounter has been taking place long before European debates on the place of Islam in Europe and the recent influx of refugees.

In order to understand this, some history is required.

Zionism, or the Jewish enterprise of creating a nation-state for Jews, started and developed as a reaction to the European entry into the nation-state system, in early modernity (starting in late 17th century and reaching its peak in the mid 19th, according to some historians.[1]The passage into this new system came together with the rise of secularism, and ideologies of civil equality, scientific authority and others. The Jewish enterprise was initiated and largely executed both by central European Jews holding these ideologies, as well as Eastern European Jews with ideologies pertaining to the socialist revolution.

There was already a Jewish population in the land of Israel, which was under Ottoman rule, but the European newcomers of the late nineteenth century were efficient and aggressive, and were supported by the ruling empire – since 1917, the British – and eventually their ideologies and social institutions were the dominant ones in the Jewish society in Palestine.[2]

Since the Zionist ideology was Jewish-focused, non-European Jews could and did take part in it; but the nation-state system with its ideologies was not necessarily dominant in all of the Muslim-dominated countries, from which these Jews arrived (most arrived after the foundation of the State of Israel in 1948, but some groups moved to Palestine earlier, such as the Yemenite Jews[3]).

The cultural different became apparent very quickly, and the European Jewish population (called Ashkenazi) tried its best to instill the nation-state ideologies to the new-comers (who are called Mizrahi) during the 1950s and 60s.

But what is considered education by one group is experienced as oppression by the other: advocating change of their original Judeo-Arabic languages and dress-code, submitting unofficial institutions to the state official ones, shaking the traditional social hierarchy and roles in the name of equality, and categorizing religious and popular-religious customs as primitive, were the sins committed by the Ashkenazi Jews against the Mizrahi, while not considered or not recognized as sins at the time.[4]

Mizrahi resistance to the Ashkenazi hegemony joined with the rise of parallel realisations worldwide, such as the rise of the post colonialist sensitivities, following Edward Said’s Orientalism, and understanding the nature of hegemonic suppression of subaltern voices.

Mizrahi resistance took many forms at least since the 1970s, with various levels of success, but one particular Mizrahi approach made the bold step of recognising the cultural closeness of Mizrahi culture and the Palestinian one, who are the traditional ‘enemy’ in the Israeli discourse, as well as the similarities in the suppression both these groups suffered.

Mizrahi culture, like the Palestinian one, belongs more to the Middle Eastern milieu, where the State of Israel is located, than the European-oriented hegemonic Ashkenazi culture. These Mizrahi activists are a relatively small group, but a high-end one, of an intellectual elite, which is very productive and visible academically and in the society. Their internet location is the site HaOkets, ‘the sting’, which can be found here: (https://enghaokets.wordpress.com/).

Within this group, there is a special place for Mizrahi feminists, who in line with parallels among minority feminism, have to resist both masculine hegemony on the gender front, as well as hegemony on a national or ethnic front (cf. Lois West, Feminist nationalism).

Prof. Lavie is active in the Israeli movement of Mizrahi Feminists called ‘Achoti’ (sister); this is their site: http://www.achoti.org.il/?page_id=414.

It is in such context that Lavie talks about Bureaucratic Torture. Influenced by the concept “bureaucratic logic” coined by the Israeli anthropologist Don Handelman, Lavie defines hegemonic bureaucracy as torture, exposing the non-realistic demands bureaucracy puts on weakened members of society, of which women, and especially single mothers are a large part.

This is also the place from which Lavie is joining Audre Lorde’s[5] call not to shy away from expressing emotions, especially those of anger or agony, in academic writing, since this is the only way to break the bureaucratic and hegemonic discourse.

This is how inner-Israeli problems can serve as a model for parallel world wide issues: Mizrahi subalterns, European vs. Middle-Eastern cultures, minority-feminism – Prof. Lavie’s topics are of acute relevance to current discourse in the public sphere.

About Professor Lavie

Prof. Smadar Lavie received her BA in Social Anthropology from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem in 1980, and her PhD in the University of California, Berkeley in 1989 in Cultural Anthropology.

She was awarded the Malcolm H. Kerr Dissertation Award from the Middle East Studies Association for her dissertation titled, “The Poetics of Military Occupation: Mzeina Allegories of Bedouin Identity under Israeli and Egyptian Rule” which was later published by the University of California Press.

Lavie is a Mizrahi U.S.-Israeli anthropologist, author and activist. She specializes in the anthropology of Egypt, Israel and Palestine, emphasising issues of race, gender and religion. She is a member of many political, feminist and anti-racist organizations.

Dr. Ronit Nikolsky. Assistant professor in the Center of Middle East Studies; specializes in Jewish Studies and Culture and Cognition.

[1] See, for example, Anderson, Benedict. 2006. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism, Revised Edition. London: Verso; Hobsbawm, Eric. 1990. Nations and Nationalism since 1790. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

[2] Cf. Shapira, Anita, Israel – A History, Waltham, MA: Brandeis University Press (2012), 142 ff.

[3] Cf. Shenhav, Yehuda, The Arab-Jews: Nationalism, Religion and Ethnicity, Tel-Aviv: Am-Oved (2003), 90-94 (Heb); Chetrit, Sami Shalom, The Mizrahi Struggle in Israel: Between Oppression and Liberation, Identification and Alternative 1948-2003, Tel-Aviv: Am-Oved (2004), 14

[4] See for example Shokeid, Moshe et al., “On the Sin We Did Not Commit in the Research of Oriental Jews”, Israel Studies 6:1 (2001), 15-33 (https://muse.jhu.edu/login?auth=0&type=summary&url=/journals/israel_studies/v006/6.1shokeid.html)

[5] Audre Lorde, Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches. Berkeley, Crossing Press 1984, 127