The scandal of women’s bodies in secular Europe

| Date: | 25 August 2016 |

| Author: | Religion Factor |

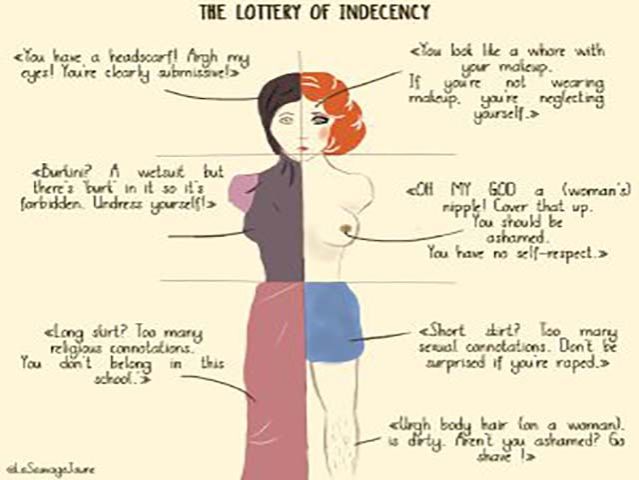

On Tuesday this week, images of a woman on a beach in Nice being forced by armed police to remove portions of her swimwear began circulating on the internet. The so-called ‘burkini ban’ has sparked outrage and controversy, not least because it is yet another variation of an age-old problem – the control over women’s bodies in public. In today’s post, Kim Knibbe vents her frustrations and reflects on the complex array of factors that contribute to women’s bodies continuing to be objects for the exercise of power.

I am furious! How should women dress so that they will be left alone, and not be the object of societal debates, religious rulings, secular lawmaking, sexual harassment and comments?

After all the fierce debates over burkini’s, hijabs, burka-bans, mandatory miniskirts and heels in some professions and the general obsession with Hillary Clinton’s appearance and what it says about her character, morals, professionalism etc. this is the very practical question I have in mind. Let me start with what I know, which does not include many Muslim women, at least not why they wear a hijab or burkini.

I know lots of good ethnographies on this, if you’re interested (check out for example, the work of Annelies Moors on the topic, and the authors associated with her projects). And from those, I understand that it has not much to do with avoiding the pressure to look good, because there is a lively fashion in hijabs and modest clothing, and many veiled women are no strangers to lingerie and make-up. But it is exactly the pressure to look good, or not just good, but ‘just right’ for your role in society, that makes things hard for ALL women, not to mention those who do not line up neatly with a heterosexual gender binary. A secular female body such as mine, the body of a white European woman who does not adhere to any religious dress code, can also not just ‘be’. So let me start with white western European women above thirty. How do we dress and present ourselves in public?

Judging by appearances, women in Western Europe take the public role of their bodies seriously. We put a lot of work into it. While on holiday in France this summer, sitting at the beach of a lake, I often looked around and tried to calculate how many hours each woman had put into her appearance that day, week, month: shaving or waxing (how much time per week?), shopping for just the right bikini or bathing suit, dress, shirt, shorts (how many hours a month?). Add two hours every two weeks for nails done professionally. Add half an hour a day for make-up, plucking unwanted facial hair, and styling hair. Not counting shower time and brushing teeth. Maybe 15 minutes or half an hour a day (minimally) exercising to stay slim and healthy? Plus time spent looking around, agonizing over your personal style, discussing this with your friends, your mother and your colleagues. Not to mention the many women who pick out the clothes for their husbands and children…

That is a serious amount of hours. All those surveys measuring how household tasks are divided within the house, did they ever take into account the many more hours women put in to simply look ‘acceptable’? Maybe it explains why women in the Netherlands still feel more exhausted despite having equal amounts of ‘free time’ according to research? And women have to do all this work to some extent secretly, because the accusation of vanity is always around the corner, the sly double standard that means you’re damned if you do and damned if you don’t, most of all by your internal voice, the super-ego or whatever you would like to call that judgmental voice in your head that keeps whispering that whatever dissatisfaction, embarrassment or discomfort with your body you’re experiencing is your own fault (in the following I will convey my internal arguments with my superego and rants against it in italics).

Take myself, and I should probably not be telling you this because, well, all the comments I will be getting but that is exactly the reason why I do tell it, because I hope that my freedom is not just a rhetorical device.

As a full time working mother, I have to choose a level of grooming to maintain, or not, and add that to the hours I allocate to each part of my life (work, time with children, with partner, household chores, getting groceries, admin). I don’t want to. It’s oppressive. (W hile I am writing this I am already thinking of the comments I will get, all collected in that judgmental super-ego voice: “you personal grooming? Not beyond a touch of lipstick and a bit of mascara surely?” Well, yes, but think of all the time spent choosing those lipsticks! And I am still wondering in which Dutch shops I can get elegant shirts that don’t show too much cleavage because secular ideals aside, showing too much cleavage while discussing secularization theory is simply not very effective to get yourself understood with 18 year old students. And why are so many dresses in main street stores too short? Cursing the world that I have to even spend time thinking about it, why are fashion designers so sadistic that they demand women should look sexy ALL THE TIME? When do I have time to find a place that sells clothes for my body type and professional status, and should I get a professional to determine my body type? Tell me if I’m a winter or summer type? How does that work with all the changes because of pregnancy, breastfeeding, aging? And the time fitting clothes takes! Because I know I won’t wear clothes that make me feel uncomfortable, and I can’t afford to waste money on clothes I will not wear, although I still waste money, and there is that judgmental voice again… )

In short, at this point in my life I do not find the joy in shopping, styling and personal grooming that commercial culture tells me I should have, but I do feel an obligation to maintain myself as a professional persona and I feel inadequate, awkward and like a frumpy housewife if I wear the wrong clothes, or have a bad hair day ( but what’s wrong with frumpy housewives? Can’t they be taken seriously? Shouldn’t I be standing up for them?).

I can understand other people do find joy in this stuff, and see it as a way of boosting their confidence, re-energizing through self care etc.. That’s fine, I’m not criticizing that. I also feel better when I think I look good. ( but why? And do men also have this to the same extent? Is it just my fault, should I just feel differently? But I don’t have the energy to let it all go and make this a feminist statement, because then I have to brush up my feminist vocabulary to defend myself against criticism, plus I will have to battle all those biases, conscious and unconscious, against women who just don’t care how they look, especially if they also happen to be mothers, the frumpy housewife spectre looms again. Although maybe if I didn’t have to spend all those hours on personal grooming, shopping, styling and agonizing I would have time for being a proper feminist? But then I don’t feel good when I think I look bad… So I would first have to exorcize society from my body and how I feel. Exorcize it like a demon. But that’s not possible, I know, I believe in habitus , we embody societal structures, I’m a social scientist after all ).

So that’s where my opening question comes from on a personal level. I just wish, for myself and for other women, and for my daughters when they grow up, that our bodies could be taken for granted, unremarkable, at whatever level of styling or grooming, revealing or not revealing we choose. I imagine that’s what I have in common with a Muslim woman who wants to go swimming in a burkini (although, as I said, I never talked to a woman who wanted to go swimming in a burkini). I know this is an impossible wish, but why? Why does this longing to be left alone seem so impossible?

A few weeks ago I was in Nigeria, visiting churches and speaking with pastors and church workers. Many, women and men, expressed their concern over women’s dressing. Many saw a direct link between women dressing improperly, and societal ills such as families falling apart, an increase in rape, corruption and even terrorism and child abuse. During an academic conference on religion and sexuality, many African academics expressed the same concerns, often coming close to blaming the victims. At the same time, several other African academics and activists problematized gender based violence in a quite different way, highlighting it as a crime. The ‘right to wear what you want’ for women, and to be what you want for queer people, in some discussions came to be pitted against what someone called the demand for ‘public decency’, which seemed to concern, again, mainly how women dress and the many ills this is thought to bring forth rather than the crimes committed against them. It seemed the divide was impossible to bridge. But why?

Why can we not agree that a person should not be harassed, raped, killed whatever that person is wearing or expressing? Should that not be a self-evident common ground between religious practitioners who have a particular standard for ‘public decency’ and secularists who think women in burkini’s are a sign of women’s oppression? Do we have to agree on standards for public decency to agree that harassment and gender based violence are not only indecent but a crime? Why could those people on the beach in Nice not stand up for that lady being forced to undress?

As an academic, I know that my wish for myself and anyone who is not a heterosexual cis male to be left alone, my body taken for granted, to be a ‘man’ in the public domain is impossible. I know all the theories: women’s bodies become signifiers for the nation state. For particular freedoms that some imagine are threatened by the Islamicization of Europe. Or of the sexualization of society. Their presentation as objects sell products faster, so they’re everywhere in various states of undress that most women do not aspire to while going about the business of their working lives. They are the ones who, through rearing children, reproduce society and therefore burdened with representing the strongest ideals of what that society should be in the face of globalization engulfing a particular way of life. They may represent the possible new society that may emerge, free from corruption, rape and abuse, if only everybody got born again, or convert to Islam, or live according to Hindutva and did not give in to worldy tempations and the flesh. Plus, the golden oldy, Simone de Beauvoir: women are the exception in public space, men are the rule. They get noticed for being women, men get noticed for their ideas, projects etc..

And yes, women also uphold all of this, so it’s not a case of women against men. But I imagine there are more women sharing this feeling of exhaustion, wondering what they should do to just BE, to be able to go about their business, without any fuss.

Looking at the fierce debates over how women should (not) dress while in the public domain, swimming, playing beach volleyball or simply while going to work and doing grocery shopping it seems there are roughly three positions in these debates: 1) Christian, Muslim, Hindu and other religious position, involving particular views on how women should dress and how they should cover themselves (and these positions are held and lived by both men and women). 2) secularist positions, which promote the view that no religiously explicit form of dressing should be allowed in public and which assumes, explicitly or implicitly, that when it comes to women, the more they wear the more they are oppressed. 3) Lastly, there is what I will simply call the post-secular perspective (just as a shorthand! Not going into the whole post-secularism debate here…).. which states that forcing women to undress in the name of secular neutrality is a contradiction, that secularity and the secular body are also particular and not necessarily ‘free’ (see my rant above) and recognizes that wearing a hijab or any other kind of hair and face covering can be a choice for women, not necessarily a sign of oppression (and yes, I take the third position).

For all these positions there are of course variations, emphasizing different principles and taking different perspectives, I am grossly oversimplifying (although I am not alone in this, since social media simplifies these debates in pointed memes, tweets and troll rants). With regard to the religious positions, I should probably emphasize that many multitudes of religiously active people are quite unconcerned with issues of how to dress, but somehow the ‘conservative’ religious positions are overrepresented in the media.

My point is that none of these positions in their variation address my simplistic question, as a woman, professional, and mother: how should a woman dress, be, behave in order to avoid becoming the subject of controversies, harassment, violence etc? As a social scientist, I am not trained to answer this question, I am only trained in understanding why this is not possible, using all the theories mentioned above, plus the basic insight that we are social animals who will always to some extent police each other.

However, as a social scientist I am also trained to flip the question around and analyze how responsibilities are distributed. I started with the question how I should be, how women should be, in order to be normal, without comment, without attracting harassment or violence or regulation and lawmaking. The fact that we even ask the question, in this form, points to the problem: it again places the burden on women and all ‘others’.

So, let’s flip the question then and ask: what is the society we should be imagining where every person, whatever they are wearing or expressing can just BE and go about their business of lying in the sun, swimming, playing beach volleyball, doing grocery shopping, walking home late at night, work? Can we imagine it across religious, cultural and other boundaries? And can we then please bring it into being already?

( and soon please to avoid further victims. Definitely before my daughters grow up. Because how should I prepare them for the eventuality that this society does not exist yet by the time they reach puberty? Or will I be complicit in reproducing a unequal and gendered society if I prepare them for it? Again, practical questions … ).

Kim Knibbe is University Lecturer in Sociology and Anthropology of Religion, University of Groningen. She co-convenes the CRCPD Research Cluster on Sexuality, Gender and Multiple Modernities