A Fragment of the Gospel of Jesus’ Wife? Part One

Last week, Karen King, Hollis Professor of Divinity at Harvard University, presented a papyrus fragment in which Jesus referred to Mary as “my wife”. The fragment seems to date from the fourth century A.D. and is written in the Coptic language.

Recent papyrological discoveries related to the world of Early Christianity such as these seem to support the view that ( pace Homer) life more often than not mirrors literature. In 2006, the publication of the Gospel of Judas by National Geographic seemed to install in our tangible world the views that Borges attributed to his fictive theologian, Niels Runeberg. Runeberg interpreted Judas´ treason as “the mystery of betrayal” by means of which God´s plan for the redemption of humanity could be brought to completion[1]. Last week, the papyrus fragment of the so-called Gospel of Jesus´ Wife seemed to provide us with another example of life copying literature. In this fragment Jesus appears to refer to Mary as “my wife”, thereby providing a more tangible background to Jesus´ fictive dream on the cross in N. Kazantzakis’s The Last Temptation of Christ (1955).

The study presented by K. King at the Tenth International Conference of Coptic Studies in Rome, the reworked version of which will appear next January in Harvard Theological Review has caused worldwide sensation. This research seems to provide ancient precedents to modern reflections on the role Mary Magdalene played in Jesus’ life. Of course the fragment does not provide witness to facts of the life of the historical Jesus, but, if genuine, it does show that Jesus’s conjugal situation already concerned early Christians as much as it does modern ones. Indeed, it might show that beside proto-orthodox claims regarding Jesus’ celibate life, other Christians in the first centuries CE affirmed that he had a wife.

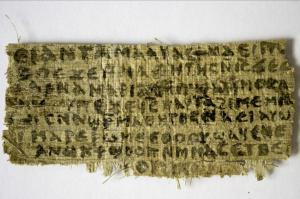

The papyrus fragment is of very small size (see images and preliminary translation on the Harvard website). ) It includes eight incomplete lines of Coptic text on one side and six on the reverse. For those acquainted with Coptic papyri, the first impression is that of a fake, since both mise en page and calligraphy are very odd: the traces of the letters are thick and clumsy, their measure very irregular, and the general appearance messy.

However, K. King is a most serious and careful scholar, and the introduction to her draft-article describes her previous consultation with different specialists, such as the papyrologist Roger Bagnall from the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World in New York and AnneMarie Luijendijk from Princeton University, who judged, weighing various factors, that the fragment was probably authentic. Ariel Shisha-Halevy, Professor of Linguistics at Hebrew University, analysed the fragment from a linguistic perspective and concluded that there are no linguistic arguments against the authenticity of the text included in it. As for the paleographical features, Professor Bagnall, who also noticed the clumsy appearance of the text, attributes it to the pen of the ancient scribe, which “ … appears to have been blunt and not holding the ink well”. Finally, Carbon 14 dating test analysis revealed that the material basis, namely the papyrus itself, is authentic and that it might be dated to the fourth century. Of course, this does not provide conclusive evidence for the genuineness of the fragment, since the forger could have used an ancient piece of papyrus. It seems consequently that we have to suspend our judgement and wait till chemical testing of the ink are fulfilled in order to provide the definitive answer regarding authenticity. However, as will be described in the next post, a lively debate has sprung up on the authenticity of this fragment as well as on the implications of the findings for the way we view the life of Jesus and the ways early Christians viewed Jesus.

Lautaro Roig Lanzillota is an expert on new testament and early Christianity at the Faculty of Theology and Religious Studies of Groningen University

read more:

J.L. Borges, “Three Versions of Judas”, in Ficciones , 1944.

Kazantzakis, The Last Temptation of Christ , 1955.

Papini, The Story of Christ , 1921.

[1] See J.L. Borges, “Three versions of Judas” in Fictions ,1944