The influence of financial instruments on the lives of enslaved people

Some groups of enslaved people in the Dutch Caribbean colonies were particularly harmed by how sugar and coffee plantations were financed. The more debt financing was used, the larger were the adverse physical consequences for forced labourers. This is evident from the preliminary results of the NWO project ‘Collateral damage: The financial economics of slavery’, on which Abe de Jong is working. For this project, the Professor of Corporate Finance analysed thousands of archival records using modern economic models and insights.

Text: Riepko Buikema, Corporate Communications; photos: Henk Veenstra

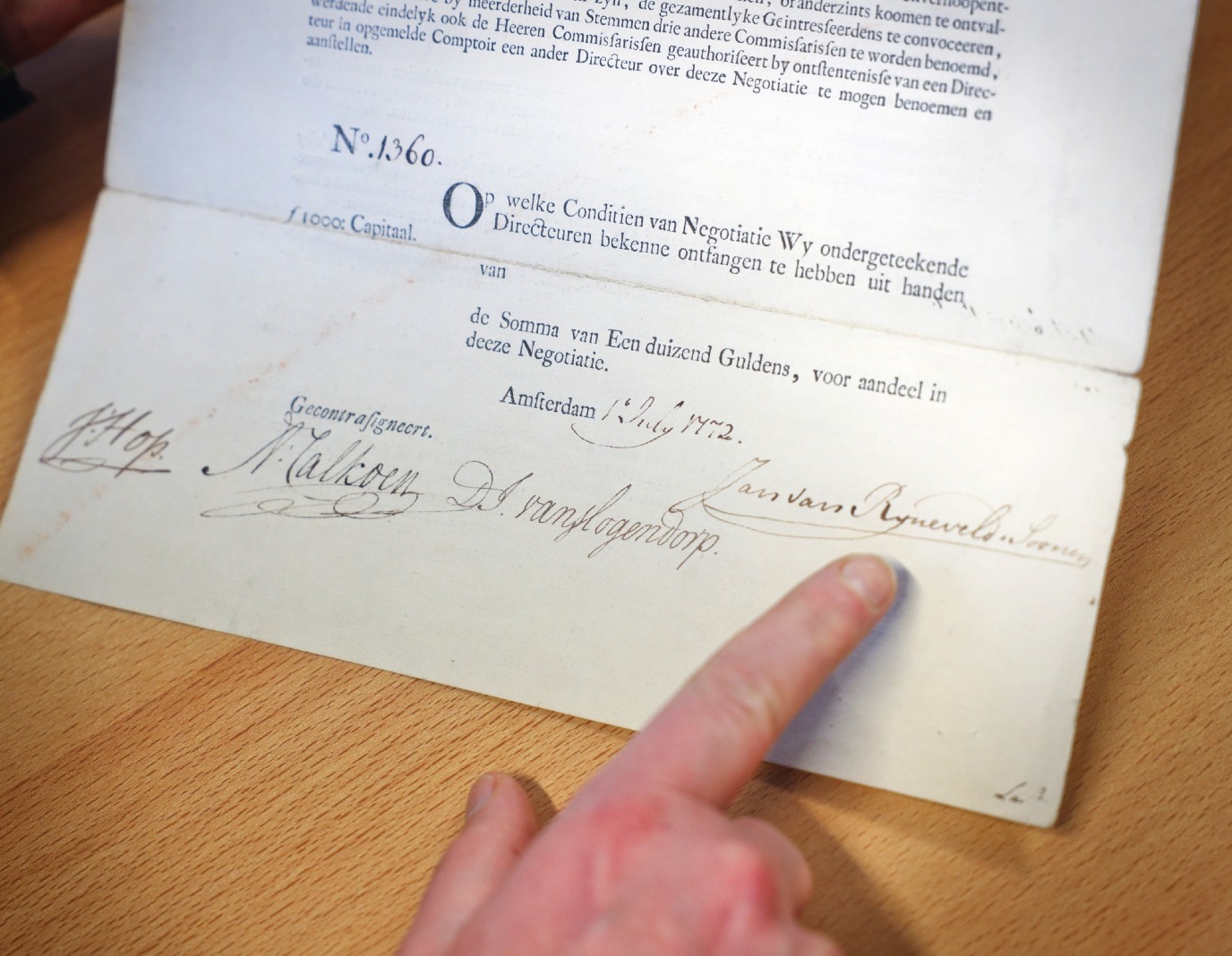

It is fascinating and terrifying at the same time. Here, on the eighth floor of the Duisenberg Building, the horrible history of Dutch slavery suddenly becomes blatantly present. ‘I often show this to people when I talk about my research,’ De Jong says, pointing at a 250-year-old document. ‘Look, these are the names of Van Ryneveld and Calkoen, major bankers from Amsterdam at the time of signing in July 1772 — the height of the hype. All the conditions of the investment are explained meticulously. See, the owner of the plantation shall pay a 6% interest rate. Very interesting.’

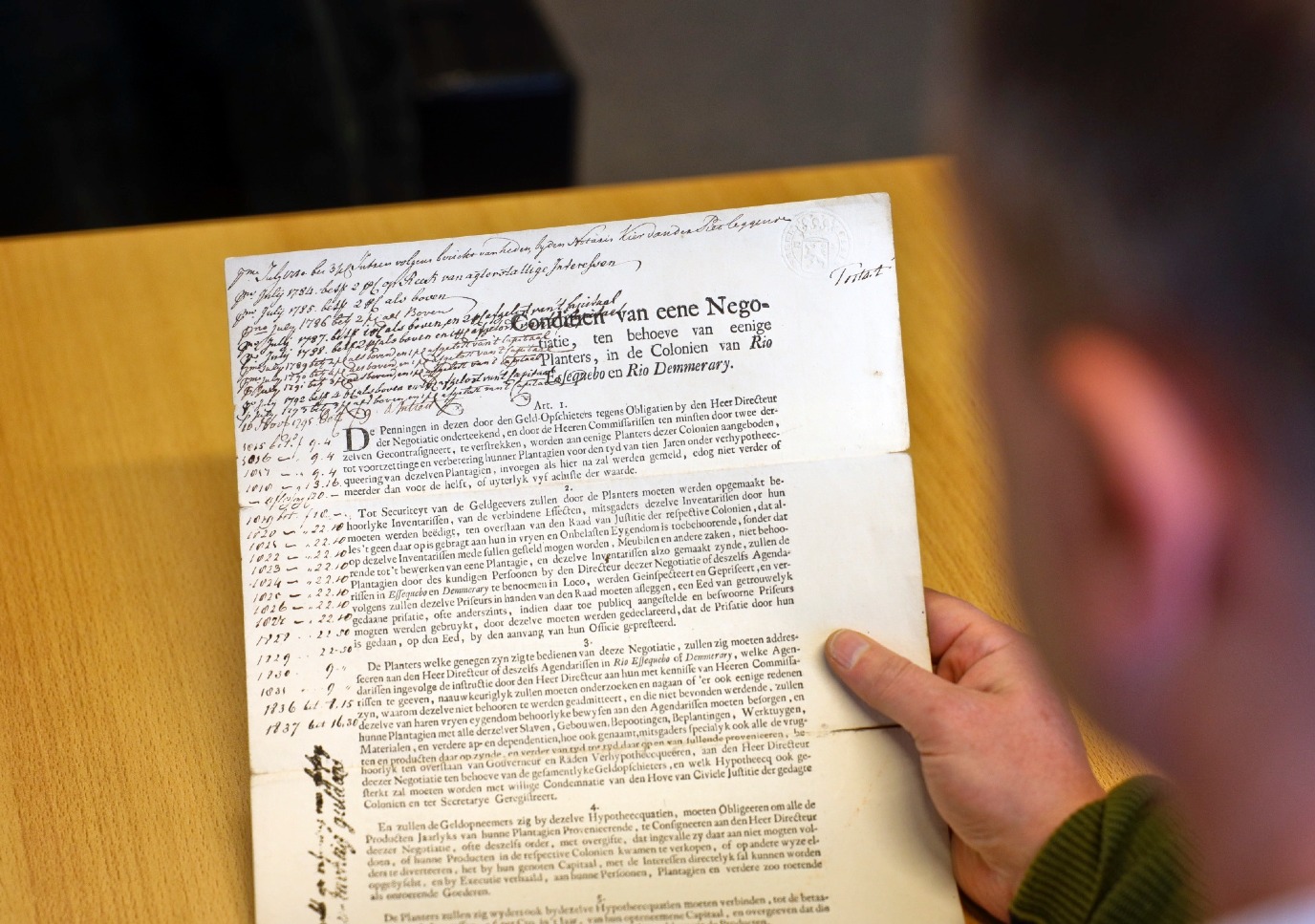

The historical document is a transcript of a so-called negotiatie; or simply: money managed by a bank and used by several influential Dutch people to collectively invest in colonial plantations. ‘Wealthy people in the Netherlands wanted to invest in the new gold: sugar and coffee of the plantations in Surinam, Essequibo Demerara and Berbice. On top of that, bankers offered the possibility to buy into shares of several plantations simultaneously, a so-called negotiatie. Capitalists found that appealing: a diversified investment, which people thought to be safe. Besides, they were assured of a collateral, as horrible as it may sound: the enslaved people owned by the plantation owners. This type of investment was incredibly popular.’

Dangerous

Until the bubble bursts and the stock prices fall. Now that there is no longer sufficient funding to buy new enslaved people, many plantations are in trouble. ‘On the plantations, the percentage of deaths is much higher than the newborns. The group of forced labourers slowly decreases, while for the plantation owners, the pressure to produce increases due to the falling coffee prices. More and more kilogrammes of coffee are needed to be able to settle the interest payments.’

The enslaved suffer from the worsening conditions. There is less money for clothing, for food. ‘Plantation inventory lists kept detailed stock of what was happening with the enslaved, for example when they were missing an arm, leg, or eye. They did incredibly dangerous work, such as operating sugar cane mills, and they worked long hours, under increasing pressure to keep the investors satisfied.’

Physical consequences

Here, the scale and type of investments play an important part, De Jong states. ‘There are many different tiers of financing. Some plantations were financed by banks, others by personal capital. And there were also differences between individual banks. Together with my colleagues Peter Koudijs from the US, and Tim Kooijmans, who works in Australia, I investigate the consequences of these investments. Our preliminary results show that the enslaved suffered the physical consequences when more debt financing was used.’

This is why the researchers are digging through heaps and piles of handwritten sources worldwide. ‘Everything that is financially relevant is on paper: the transfer of a plantation in a sales agreement, the mortgage on a plantation as part of a negotiatie, lists of valuations, and the possessions of a plantation, including the enslaved. We use archives in Amsterdam, Rotterdam, London, and in Surinam and present-day Guyana. We draw from archives of bankers and notaries and use the auction reports in specific newspapers.

Economic viewpoint

The affinity with historical sources is clear from his study. De Jong’s bookshelf is pervaded with history, with, at the top — an orange-brown cover — the complete yearly series of Van Oss’ Effectenboeken (on securities listed at the Amsterdam Stock Exchange), going back to 1903. ‘The great thing is that you can very precisely map the financial flows,’ De Jong says. ‘The downside is that we paint a very one-sided picture. We cannot picture the experiences of the enslaved on the plantations, that is the limitation of our research. Our added value is the economic viewpoint, we analyse what happened in numbers and connect these to the consequences of this financing modality.’

That is a challenge, according to De Jong, who is happy with the UG Faculty of Economics and Business, where he arrived in 2021 from Australia. ‘We combine complex, historical data with modern economic models and tools. It really is interdisciplinary, at the intersection of history and economy. It’s not a given that our type of research is appreciated. But here in Groningen it is, and that’s exceptional.’

Relevant

That is why in this room in the Duisenberg Building, a map of the expeditions of the Dutch East India and Dutch West India Company hangs on the wall. ‘I hope to be able to contribute to the discussions on the history of Dutch slavery by uncovering certain mechanisms, by showing that the reputation of banks influences financing, and that financing in turn influences the system of slavery. That’s very interesting, also today. In the United States, during the financial crisis of 2007-2008, the most respectable banks were the ones that went down the fastest, which is the opposite to what we find in our research period of the Dutch colonial time. Besides, it is important to map the consequences for later generations: do the descendants of enslaved people also suffer from this financing modality? We want to track them and their families across time, until the beginning of the 20th century. Peter, Tim, and I have been researching this for over ten years, but the story is not yet finished.

More information

More news

-

16 December 2025

How AI can help people with language impairments find their speech

-

09 December 2025

Are robots the solution?

-

18 November 2025

What about the wife beater? How language reinforces harmful ideas