Farewell to life sentences

A visit to a detainee in Norgerhaven prison and the ruling in the case of Lucia de Berk in around 2003 got Wiene van Hattum thinking about the sense of life prison sentences in the Netherlands. For many years afterwards, she was a firm proponent of humane ‘life’ sentences. In April, she will be leaving the University. ‘A government must make it clear that everyone counts.’

Text: Eelco Salverda / Communication Office UG

A newspaper cutting about the serial killer Hans van Z. on her door is all the proof you need that this room belongs to Wiene van Hattum, Assistant Professor of Criminal Law. But more importantly, founder, chair and figurehead of Forum Levenslang. The Forum, which when translated stands for ‘Forum for the humane enforcement of life prison sentences’, fights to offer people serving a life sentence the hope of release.

Agitator

In the programme for her farewell conference, Van Hattum is presented as an ‘agitator’. She laughs it off. ‘It seemed more appropriate than Assistant Professor. I try to set the wheels in motion and tend to go against the grain. I keep coming back to the fact that these days, a life sentence in the Netherlands simply isn’t humane. You only have to look at our history of life sentences to see the difference. It’s worse than it’s ever been. I’ve seen old pardon files at the Ministry, read how detainees went through the prison system, what happened to them. And about the commitment shown by social workers and civil servants at the Ministry at the time. You can’t help but think: have we gone completely mad?’

Hope

So what would be humane? A poster on the wall represents Van Hattum’s vision. A drawing of bars with a caption about the difference between the guillotine and a life sentence. In the first instance, your life is destroyed in a single blow; in the second, it’s destroyed bit by bit. ‘If you take away someone’s hope, you might as well condemn them to death. Hope is what keeps people going. Nothing happens if you just sit still. By sounding the alarm, we’ve shown that our attitude to life sentencing these past 15-20 years simply isn’t acceptable. You must be prepared to give people hope, even against your better judgement. That is not unethical, it’s humane.’

How long is life?

Until 2004, in principle a life sentence in the Netherlands did not actually mean life, but a long sentence aimed at resocialization. Release was considered after 15 (and later 10) years. This was an individual decision. In practice, a change in ideas about punishment, and confusion about what a life sentence was after the ruling in the case of Lucia de Berk, meant that life did actually mean life. But the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) imposed limits on giving life sentences. To take into account the objections from the ECHR, in 2016 Dutch State Secretary Dijkhoff amended the policy to include an assessment that begins after 25 years. Van Hattum has a different view. ‘I think you need to consider how individual detainees have developed. The new procedure for life sentences won’t give people hope. Nothing is being measured. You have to wait 25 years and then we’ll see whether you’re allowed to work on your personal development. These skills will obviously have deteriorated in the 25 years that have passed. Surely this isn’t what the European Court intended? I hope we’ll soon see a test case brought before the ECHR.’

Lucia de Berk

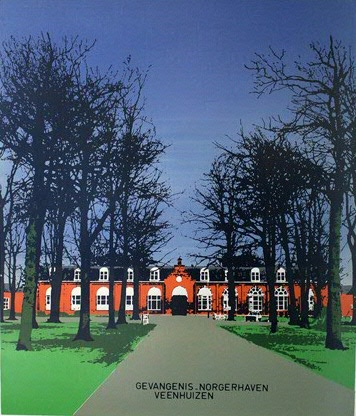

Van Hattum says that she’s always been fascinated by criminal law and detainees. After meeting someone serving a life sentence in Norgerhaven prison, her interest grew. At this time, Lucia de Berk had just been sentenced to life imprisonment and detention under a hospital order (a sentence that was overturned when she was later found innocent). ‘It was a ridiculous ruling. The combination wasn’t even legally feasible. It was as if they were doing everything they could to ensure that she never return to society. While detention under a hospital order is designed to help people rehabilitate. When government members started voicing opinions too, I thought: OK. That’s enough. I need to do something about this.’

Human side

Who is Van Hattum actually fighting for? For the detainees or for society? ‘I’m not fighting for the release of prisoners come what may. And I’m not against the principle of life sentencing. But the punishment must offer some prospect of release for detainees who manage to turn their lives around. That’s what the law says, isn’t it? Sanctions are aimed at a return to society. I don’t think that society should be inhumane. The government must make it clear that everyone counts, show its human side. Set an example, so that people will start treating each other with more respect. That’s what I believe in.’

Angry reactions

Isn’t retribution an important and legitimate part of punishment and a comfort to the next of kin? ‘You often hear next of kin saying that have also been sentenced to life,’ replies Van Hattum. ‘But I don’t think you can compare these two things. Pain and grief for the rest of your life is different from punishment for the rest of your life. And will it really make you feel any better if you know that someone is enduring a dead-end punishment? I think that next of kin would be better served by professional help than by punishment.’ ‘When I started my campaign ten years ago, I regularly received angry e-mails,’ continues Van Hattum. ‘I always replied if they weren’t anonymous. I sometimes got to talk to the people concerned, and they usually understood my point of view better afterwards. Thank heavens; the last thing I want to do is antagonise victims. I try to explain that I’m not fighting for the release of dangerous criminals; I just want to give people the chance to show that they are no longer dangerous.’

Legacy

What is she most proud of? ‘Proud?’ Van Hattum chews the word over, surprised, almost amused, as if the term doesn’t apply to her work. This is followed by a long silence. Then she says: ‘I’m certainly satisfied with what I’ve been able to teach students about life sentencing and what sanctions mean.’ She returns to the question a little later. ‘That the Forum has had an impact. That I dared to go against the grain and say: this is wrong. I think that’s what I’m most proud of.’ No, she still hasn’t had enough, she says, and she’s never felt discouraged. ‘I was often proved right. That boosts your confidence.’ Having said that, the new regulation has made her feel dejected for the first time. ‘Perhaps it won’t be as bad as I think. After all, you must never give up hope!’ she smiles.

More information

- Wiene van Hattum