Olaus Magnus’ Monstrous Creatures

The Special Collections at the University of Groningen and Uppsala University are linked through their ownership of Olaus Magnus’ two most famous works: his Carta Marina, printed in Venice in 1539 and now held by Uppsala University, and his book Description of the Northern Peoples (Historia De Gentibus Septentrionalibus, Earumque Diversis Statibus, Conditionibus, Moribus, Ritibus, Superstitionibus, Disciplinis ...) printed in Rome in 1555, of which the University of Groningen Library holds a copy. These two objects are closely related, and this relationship becomes evident when focusing on one of the most interesting aspects of both works: their emphasis on sea monsters.

Olof Månsson, later known as Olaus Magnus (1492-1557), was born in Linköping, Sweden and most famous for his descriptions of the ‘northern countries’, the peoples living there, and their customs, everyday life, beliefs and folklore. After spending a number of years traveling throughout Scandinavia and northern Europe, the catholic Magnus ended up spending the latter part of his life in exile in Italy after the Reformation took hold of Sweden [1]. Based on his personal experiences, literary sources, and hear-say, Olaus Magnus set out to create his two life’s works. Magnus was among the first to provide an accurate and detailed map of the broader Scandinavian region, and the first to provide a systematic (almost encyclopedic) account of all aspects of the region’s landscapes and peoples. At his time of writing, the northern countries were predominantly unfamiliar to most southern Europeans [2]. In his personal notes, Magnus expresses a wish to describe the marvelous things, both on land and at sea, to be observed in the northern countries and as of yet unknown to Greek and Latin authors [3]. Through his Carta Marina and the Historia De Gentibus Septentrionalibus, Magnus wanted to correct the faulty representation of the North that was found in earlier maps. Additionally, the devout Catholic Magnus wished to show the Catholic Church that the valuable and interesting North had been lost to Lutheranism and was in dire need of salvation [4].

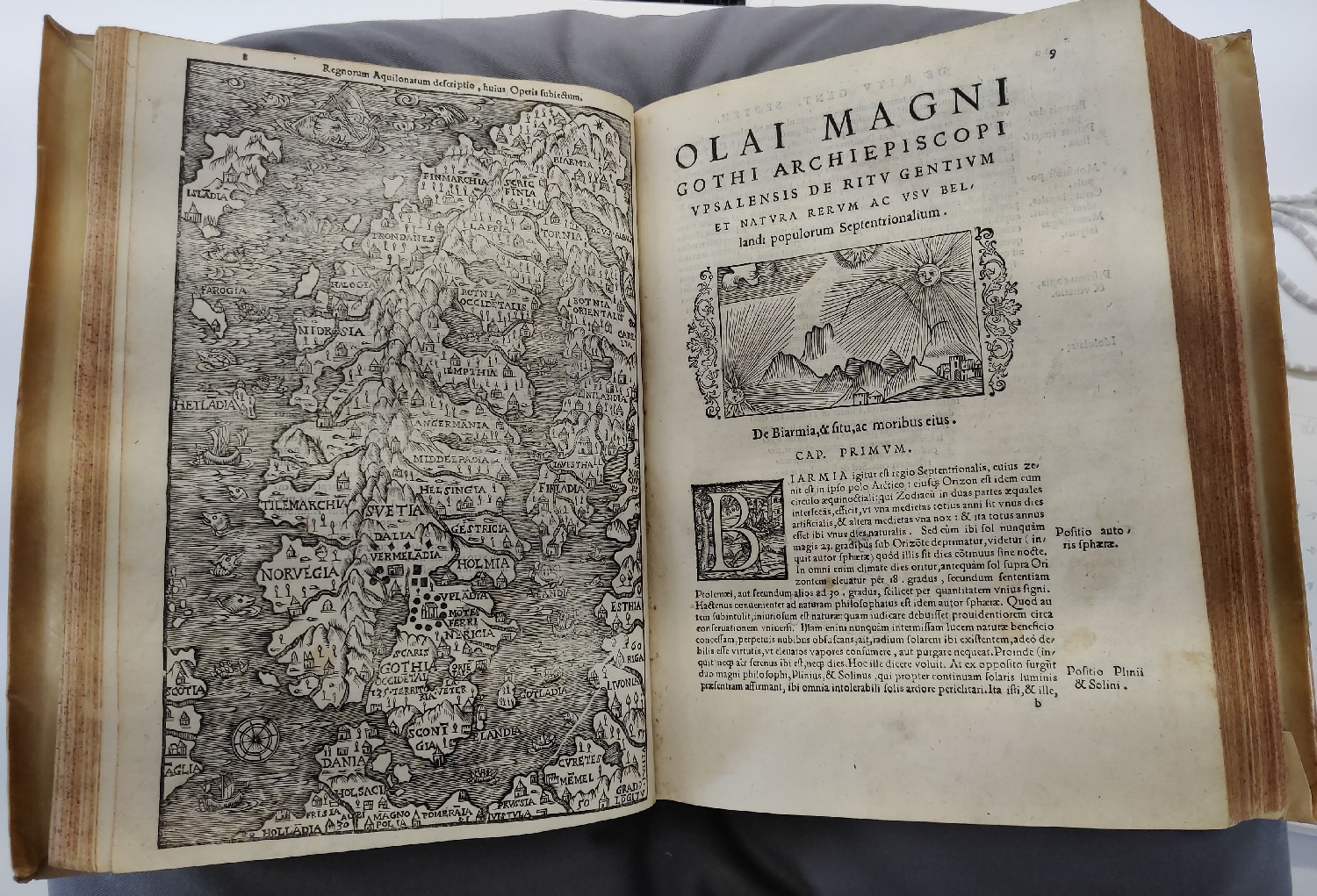

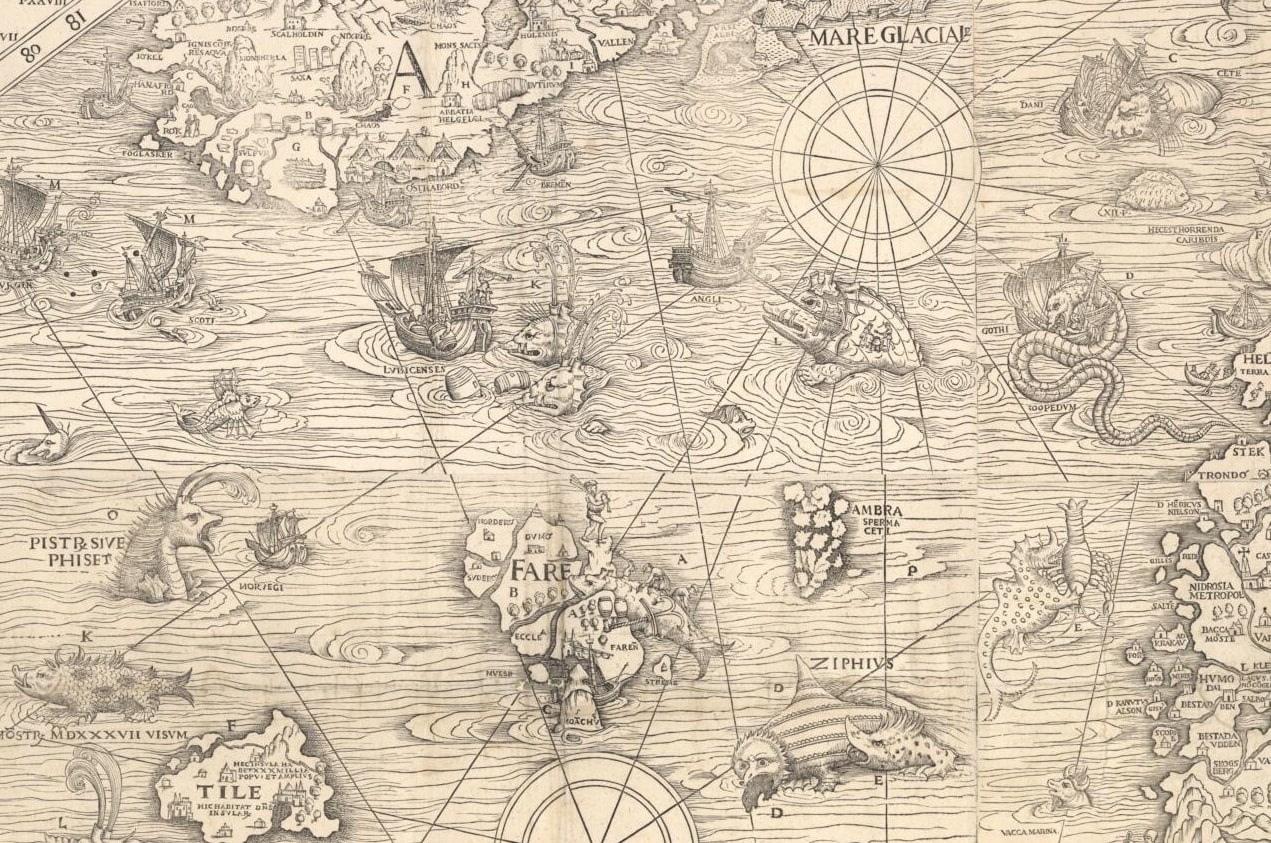

Magnus’ Carta Marina has been described as one of the most remarkable early-modern maps, being the most accurate map of Scandinavia for a long time and subsequently serving as a model for numerous later cartographers [5]. Measuring a total of 170 x 125 cm, Carta Marina was one of the largest maps printed throughout the sixteenth century, and consisted of nine separately printed sheets. In contrast to most maps, the Carta Marina was a woodcut and not a copper engraving. The map itself is divided into nine sections, labeled from A to I, and features an explanatory key. The Carta Marina is most remarkable in its amount of detail: instead of providing a purely geographical rendition of the region, Magnus has filled his rendition of the North with countless images, including images of flora and fauna, buildings and ships, and individuals and groups of people.

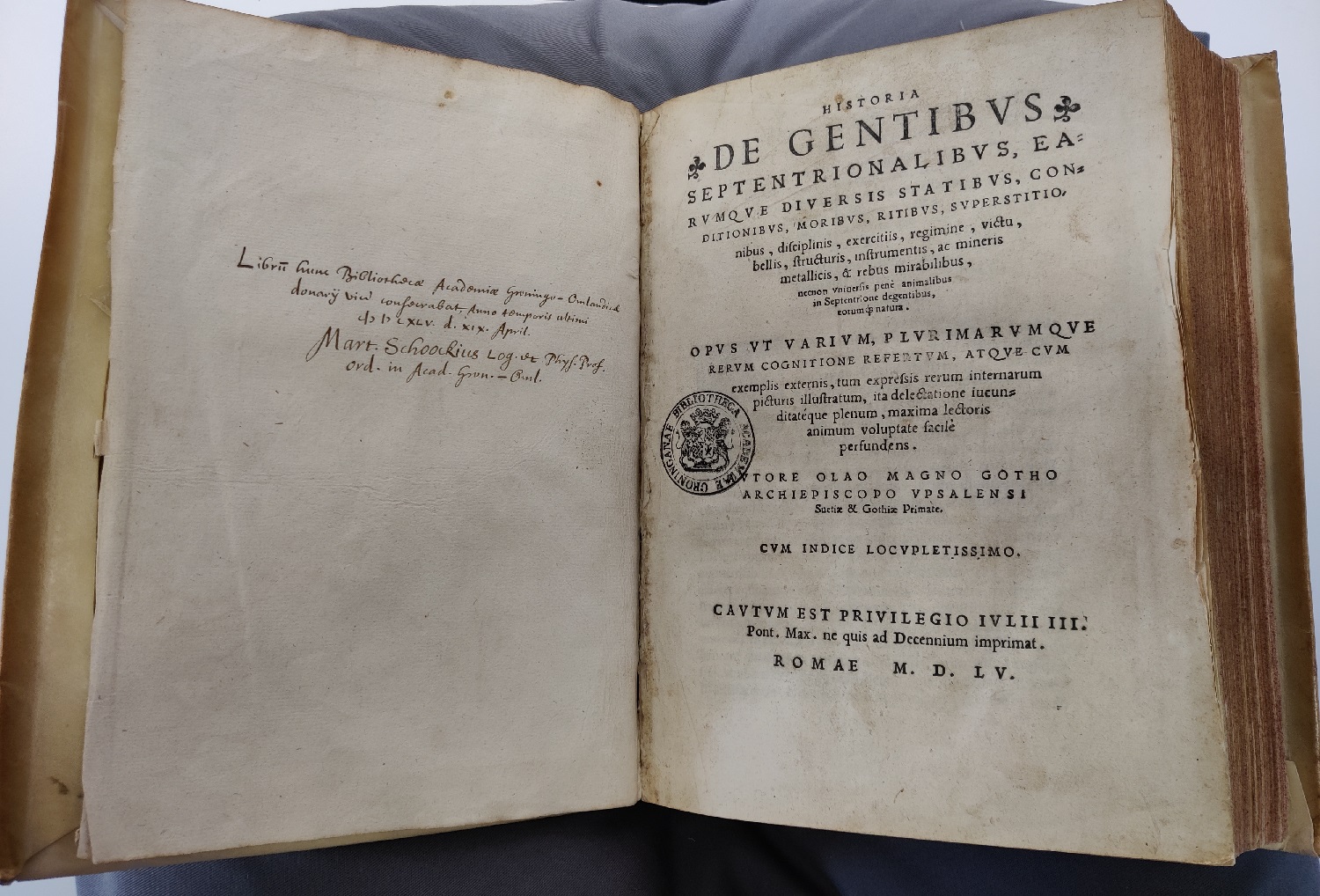

Magnus’ Historia De Gentibus Septentrionalibus [see Image 2] was initially intended to act as a short additional commentary to the Carta Marina, but ended up as an encyclopedic description of the northern regions, a work so large it was divided into 22 parts or ‘books’ and a few hundred chapters. Originally written in Latin and printed in Rome in 1555, later editions were published in German, Italian, Dutch, and English [6]. In his Historia, Magnus includes all information related (however remotely) to the regions and peoples he describes, from wars and royal lineages to detailed descriptions of peoples and their specific habits, and from historical episodes to meteorological information. While some of the information he includes seems out of place or distributed chaotically, in general Magnus tried to bring coherency to his vast stores of knowledge by dividing his information into books and chapters devoted to specific topics [7]. When laying the Carta Marina and the Historia side by side, the topical and graphical relationship between the two works becomes clear almost immediately. The Historia features a small and simplified version of the Carta Marina between the Index and the proper text of the Historia [see Image 3]. Additionally, about one hundred of the images that appear on the Carta Marina are reproduced in the Historia, in very similar or almost identical fashion [see Images 4-6]. While the images appear without context on the Carta Marina, Magnus explains in detail what is depicted on the map, as well as providing additional information related to that chapter’s topic [8].

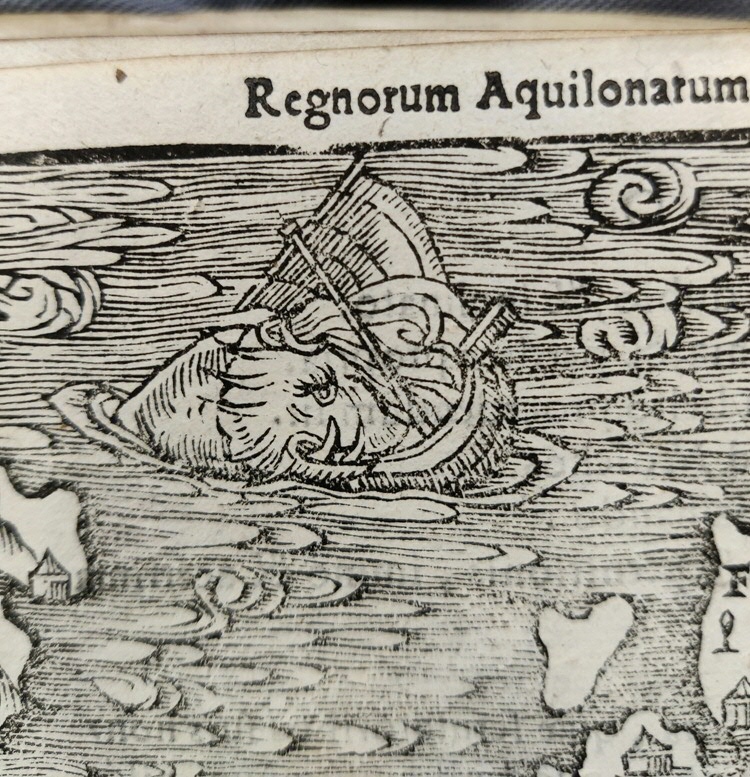

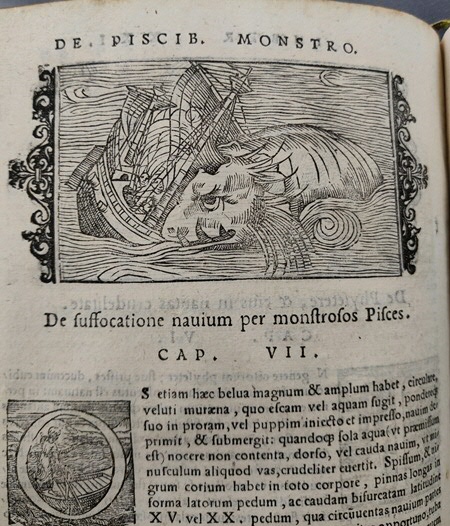

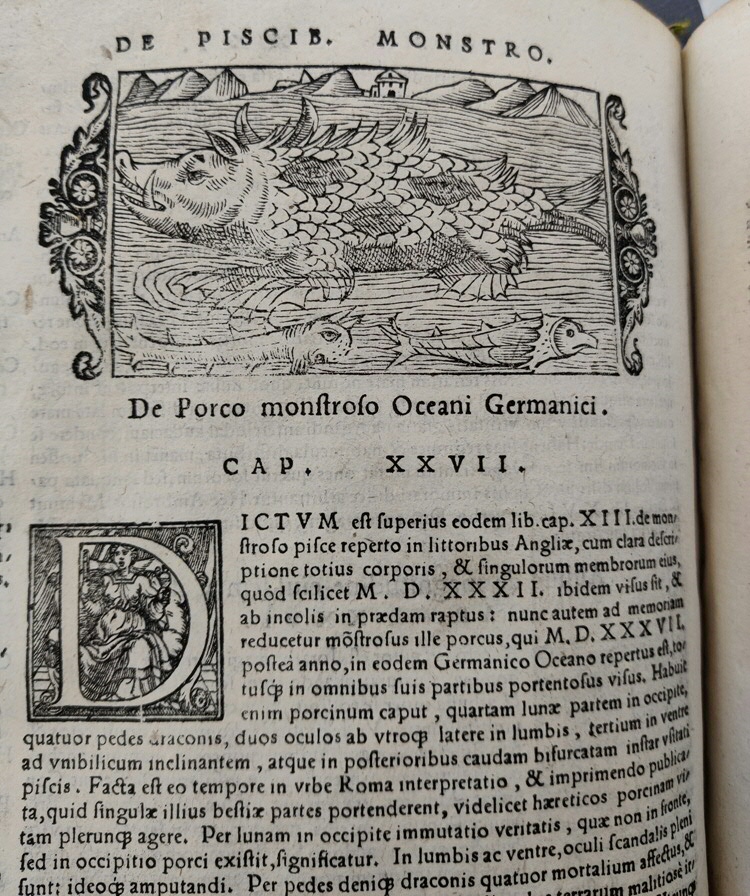

Magnus’ works are remarkable in their emphasis on bodies of water, as opposed to many earlier maps. Where other maps pushed seas and oceans to their outer borders, half of Magnus’ Carta Marina is devoted to water and the creatures and activities related to it. The Historia includes countless pages devoted to the waters, with sections and chapters on naval trading and warfare, sea creatures and fishing habits, and many of these chapters open with a header image almost identical to the images found on the map. This relationship between the Carta Marina and the encyclopedic and explanatory Historia can be seen clearly in Magnus’ treatment of one of the most striking (and possibly surreal) elements on the map: the sea monsters depicted in the sea between Norway and Iceland [see Image 7]. Magnus displays many fish and monstrous fish on the Carta Marina, and his Historia includes chapters ‘On Fish’ and ‘On Monstrous Fish’, although the distinction between the two is not always clear, especially on the Carta Marina. In the Historia, some of the creatures are treated merely as part of the natural environment, whereas others are given a moral or metaphorical meaning. A fascinating example is Magnus’ treatment of the sea-pig [see Images 8-9].

In the Historia, Magnus describes this monstrous swine-fish hybrid as follows:

“It had a pig’s head with a crescent moon at the back, four dragon’s feet, a pair of eyes in its loins at each side, and a third on its belly towards the navel; at the end was the bifurcated tail of a normal fish. In the city of Rome at that time an interpretation was printed and published, explaining the significance of the beast’s individual parts, which showed how heretics generally pursue a swinish existence. By the moon behind the head is meant distortion of the truth, since it grows not on the pig’s forehead but at the nape of its neck. The eyes in its loins and belly are full of temptation, and for this reason they must be cut out. Lastly, the four dragon’s feet signify the grossly evil desires and acts of mankind, bursting in viciously from the four corners of the earth, and appearing in the fish very much as though it were some prying ruffian.” [9] (XXI: 27; Vol. 3, p. 1110) [10]

This creature has been called the map’s most literally monstrous monster, and is said to symbolize the ongoing religious upheavals in the 16th century. The sea-pig represents the deadly sins of lust and greed, which the devout Catholic Olaus Magnus believed to be inherent within the Lutheranism that was rapidly spreading in the north. During his time in Italy, Magnus became actively involved in the Roman Catholic Counter-Reformation, and his personal beliefs are thus echoed in his map and book [11].

The monstrous sea-pig was not a figment of Magnus’ personal imagination, but was copied from a pamphlet published in Rome in 1537. As a result of the religious upheavals during the 16th century, theologically critical and satirical pamphlets became increasingly popular, and the pamphlet Magnus used as his source for the sea-pig can be seen as the Catholic counterpart to popular Lutheran pamphlets such as the Interpretation of Two Terrible Figures as the monk-calf and pope-ass, by Philippus Melanchthon and Martin Luther [12]. While the image on the Carta Marina merely shows another monstrous fish, a topic so popular that Magnus devoted an entire book of his Historia to it, the description given in the Historia provides a deeper layer of meaning to the illustrations on the map.

On their own, both of Olaus Magnus’ major works are extraordinary works of science and of art. However, when the Carta Marina and the Historia are seen in light of each other, compared and contrasted, and used in tandem, a whole new world of information and layers of meaning become apparent.

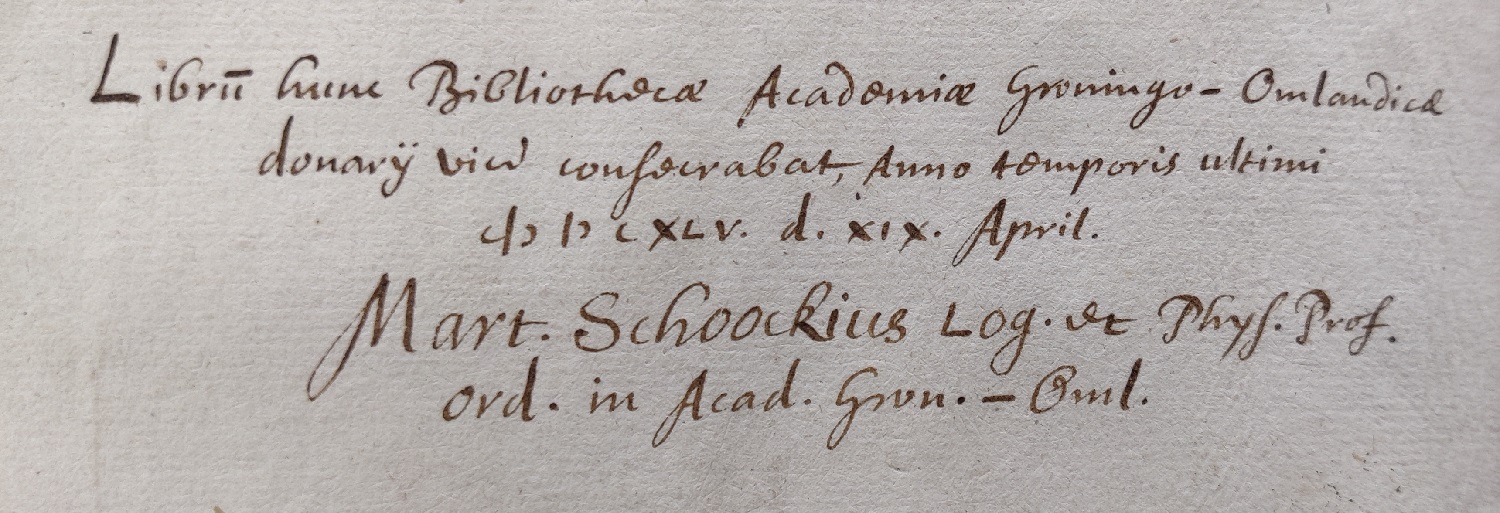

For these objects to have ended up where they are today is a mere chance of fate: the Historia was donated to the University of Groningen on April 19, 1645, by one of its professors, Martinus Schoockius, as is detailed in an inscription on the front flyleaf [see Image 10]. The Carta Marina held by Uppsala University is one of only two copies known today. Well into the end of the 19th century, all copies printed during Magnus’ lifetime had disappeared seemingly without a trace, until a copy was found among the Scandinavian maps at the Hof- und Staatsbibliothek in Munich [13]. A second copy was found in the possession of Polish collector Count Emeryk Hutten-Czapski, who contacted Uppsala University and sold his copy of the Carta Marina in Genève 1962 [14]. The Latin commentaries on both copies clearly show that Olaus Magnus intended to circulate the two maps in different parts of Europe. The Uppsala copy was published in honour of the most serene Doge Pietro Lando, the Council of Venice and for the general benefit of the Christian world (quam ad laudem serenissimi Ducis Petri Landi Senatusque Venet. ac publicam christiani orbis utilitatem emitto). The Munich copy was published in honour of the celebrated Germanic and Gothic nations and for the general benefit of the Christian world (quam ad laudem inclite Germanice et Gothice nationis ac publicam christiani orbis utilitatem emitto) [15].

Due to both their artistic and historic value, Olaus Magnus’ works remain of great interest to modern day scholars. The combination of factual information and fantastical and metaphorical representation, as well as aesthetic merit, give Magnus’ works the power to engage and marvel their audience centuries after their creation.

Notes

- Elena Balzamo. “Om den ”lyckliga slumpen”: Carta marinas öden och äventyr: Olaus Magnus (1492–1557)”: 4-5.

- Dario Del Puppo. “All the World is a Book: Italian Renaissance Printing in a Global Perspective”, Textual Cultures 6, no.2 (2011): 5.

- Leena Miekkavaara. “Unknown Europe: The Mapping of the Northern Countries by Olaus Magnus in 1539.” (2008) 5.

- Leena Miekkavaara. “Unknown Europe: The Mapping of the Northern Countries by Olaus Magnus in 1539.” (2008) 4.

- Elena Balzamo, “Om den ”lyckliga slumpen”: Carta marinas öden och äventyr: Olaus Magnus’ (1492–1557)”: 4-5.

- Harry B. Weiss. “Olaus Magnus, Credulous Zoologist, and Archbishop of the Sixteenth Century”, Journal of the New York Entomological Society 38, no, 1 (1930): 36.

- Barbara Sjoholm. “‘Things to be Marveled at Rather than Examined’: Olaus Magnus and ‘A Description of the Northern Peoples’”, The Antioch Review 62, no.3 (2004): 247.

- Barbara Sjoholm. “‘Things to be Marveled at Rather than Examined’: Olaus Magnus and ‘A Description of the Northern Peoples’”, The Antioch Review 62, no.3 (2004): 250.

- E. Sandmo. “Dwellers of the Waves: Sea Monsters, Classical History, and Religion in Olaus Magnus’s Carta Marina”. Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift–Norwegian Journal of Geography 74 (2020): 245.

- Olaus Magnus, transl. Peter Foote, and Hakluyt Society. Description of the Northern Peoples, 1555. Volume Iii (Farnham, Surrey, England: Ashgate Pub, 2010): 1110.

- E. Sandmo. “Dwellers of the Waves: Sea Monsters, Classical History, and Religion in Olaus Magnus’s Carta Marina”. Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift–Norwegian Journal of Geography 74 (2020): 239.

- E. Sandmo. “Dwellers of the Waves: Sea Monsters, Classical History, and Religion in Olaus Magnus’s Carta Marina”. Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift–Norwegian Journal of Geography 74 (2020): 245.

- Elena Balzamo, Om den ”lyckliga slumpen”: Carta marinas öden och äventyr: Olaus Magnus’ (1492–1557) Biblis 37, 2007, p. 4-5.

- Lars Munkhammar. “När Carta marina kom till Uppsala; Från handskrift till XML: informationshantering och kulturarv: humanistdagarna vid Uppsala universitet” (2002), 61-64.

- Leena Miekkavaara. “Unknown Europe: The Mapping of the Northern Countries by Olaus Magnus in 1539.” (2008), 31-32.

This exhibition was curated by Sanna Nyholt and Madelief Albers for the Things That Matter summer school, in the context of U4Society Network in which Groningen and Uppsala participate.