1450-1550

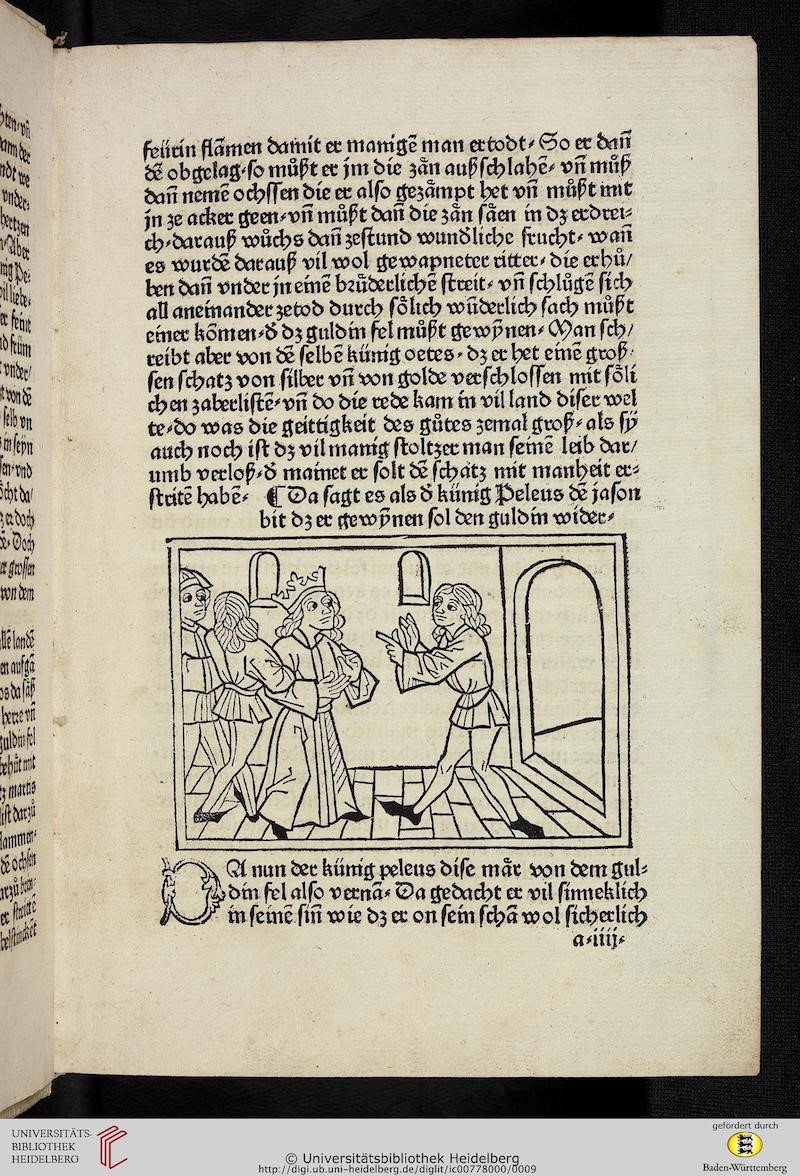

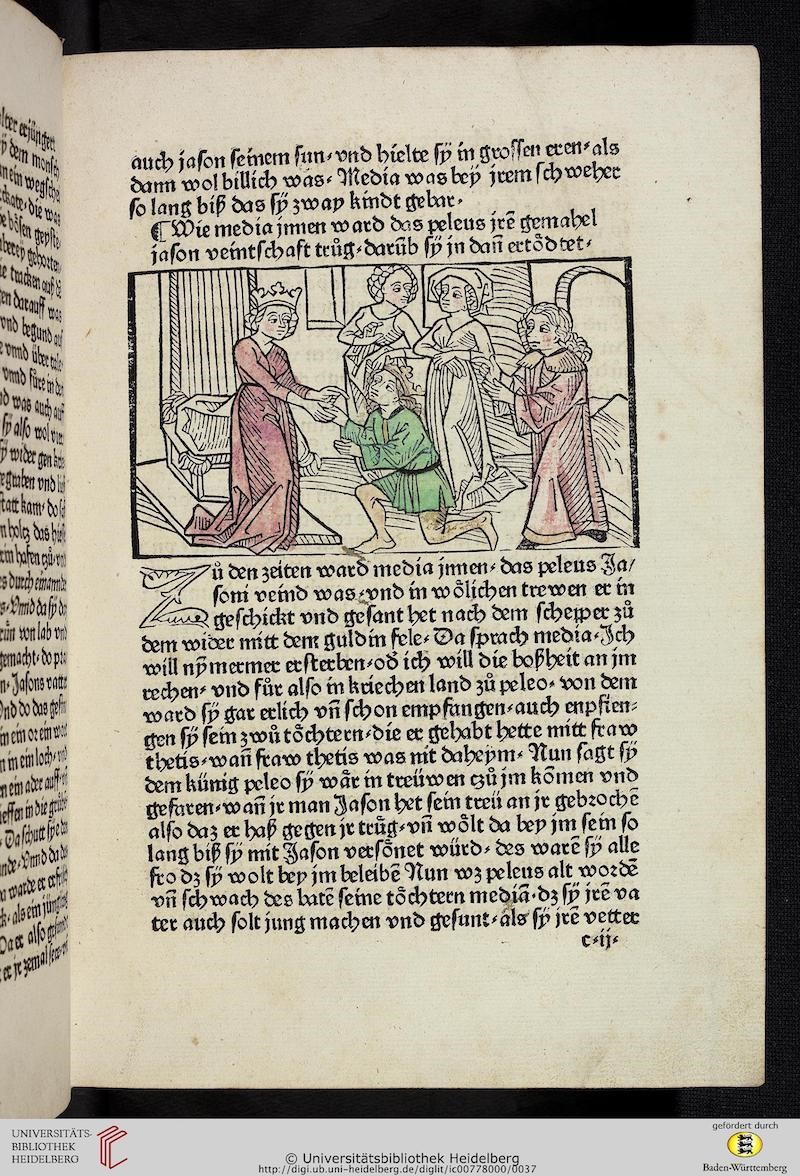

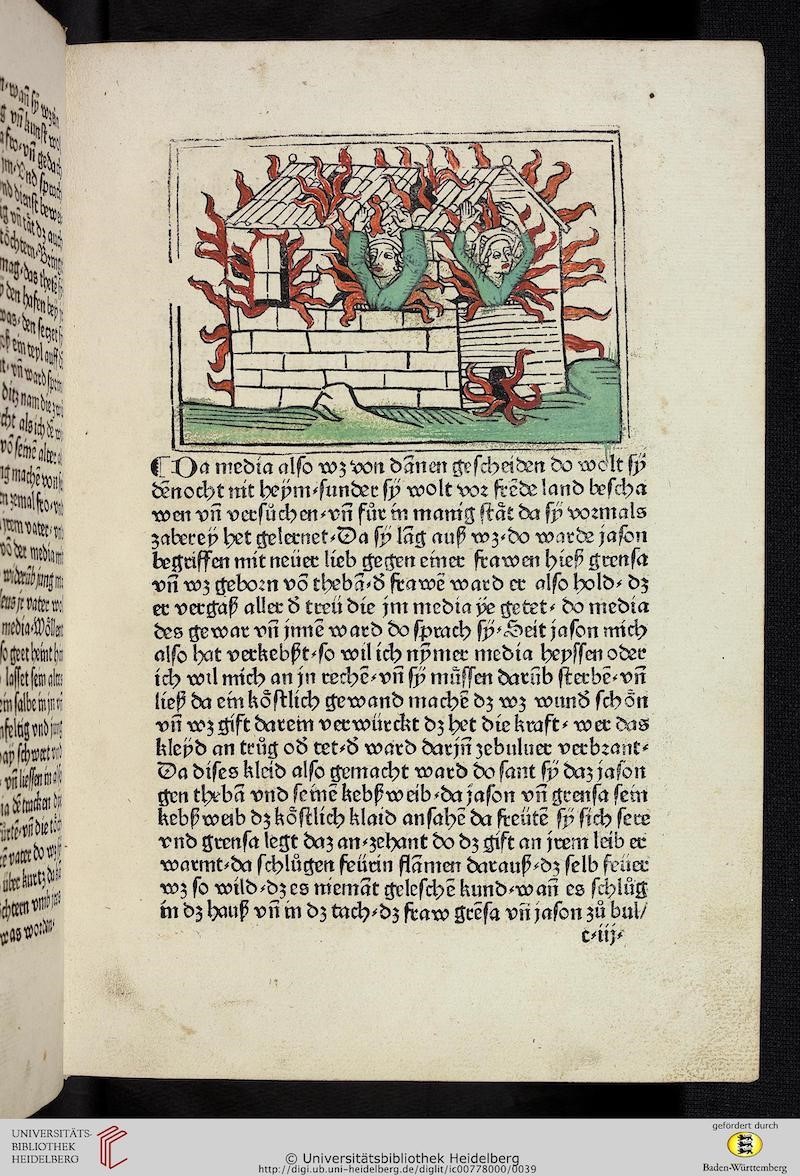

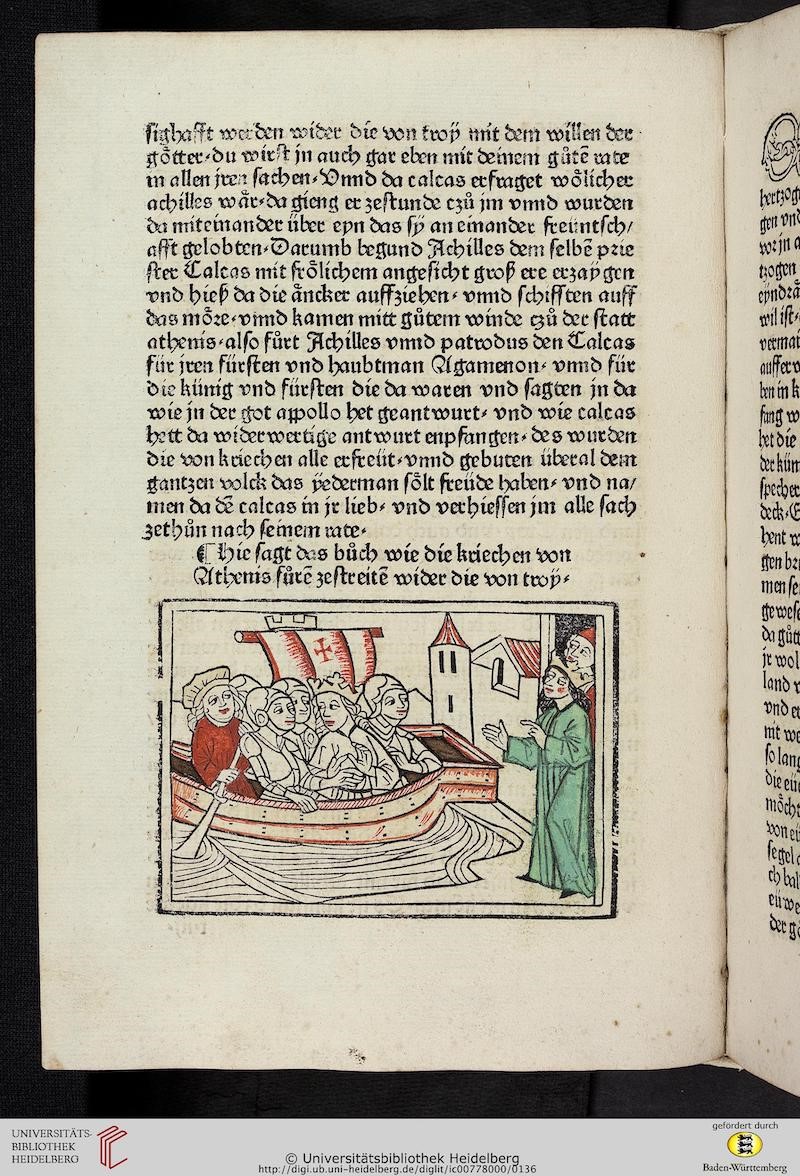

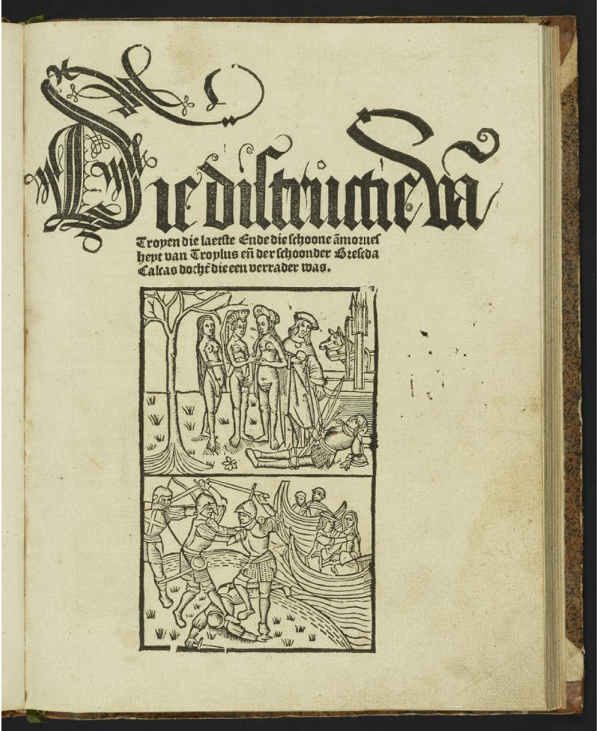

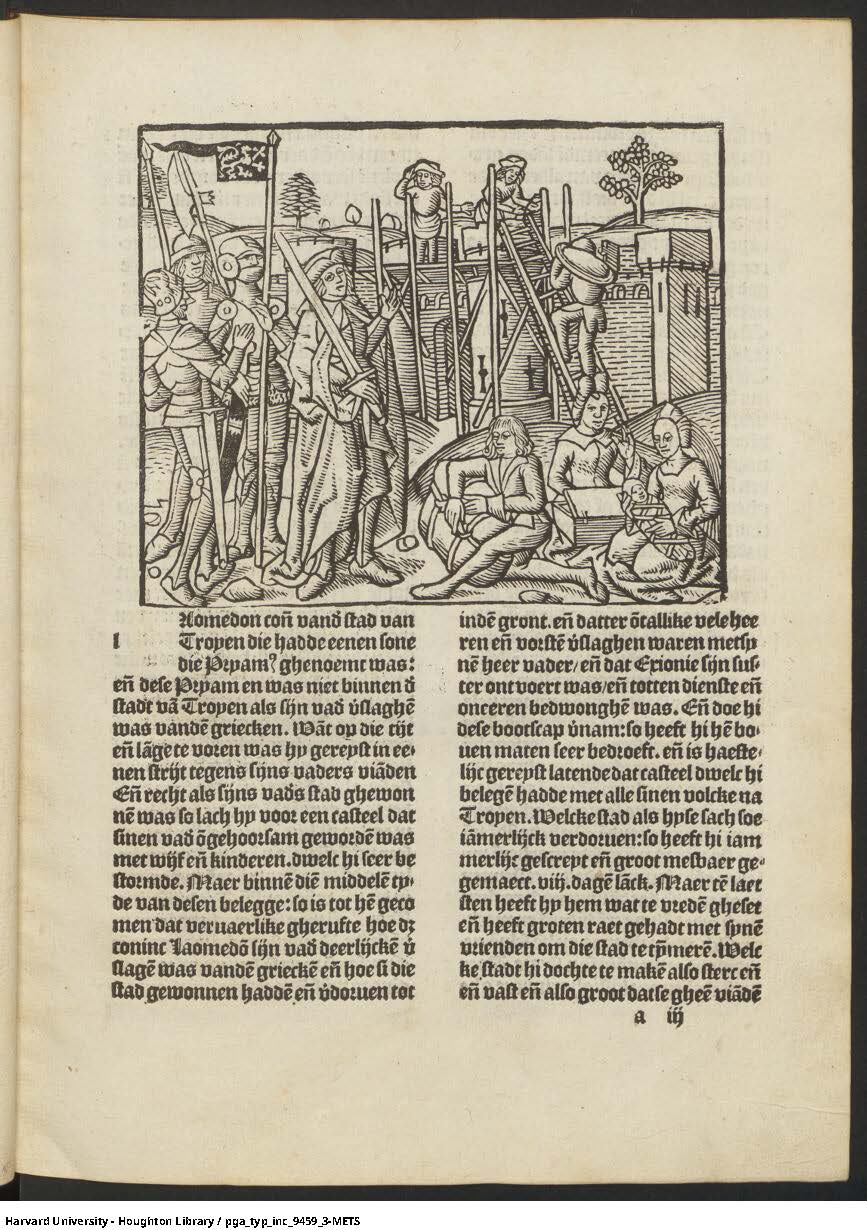

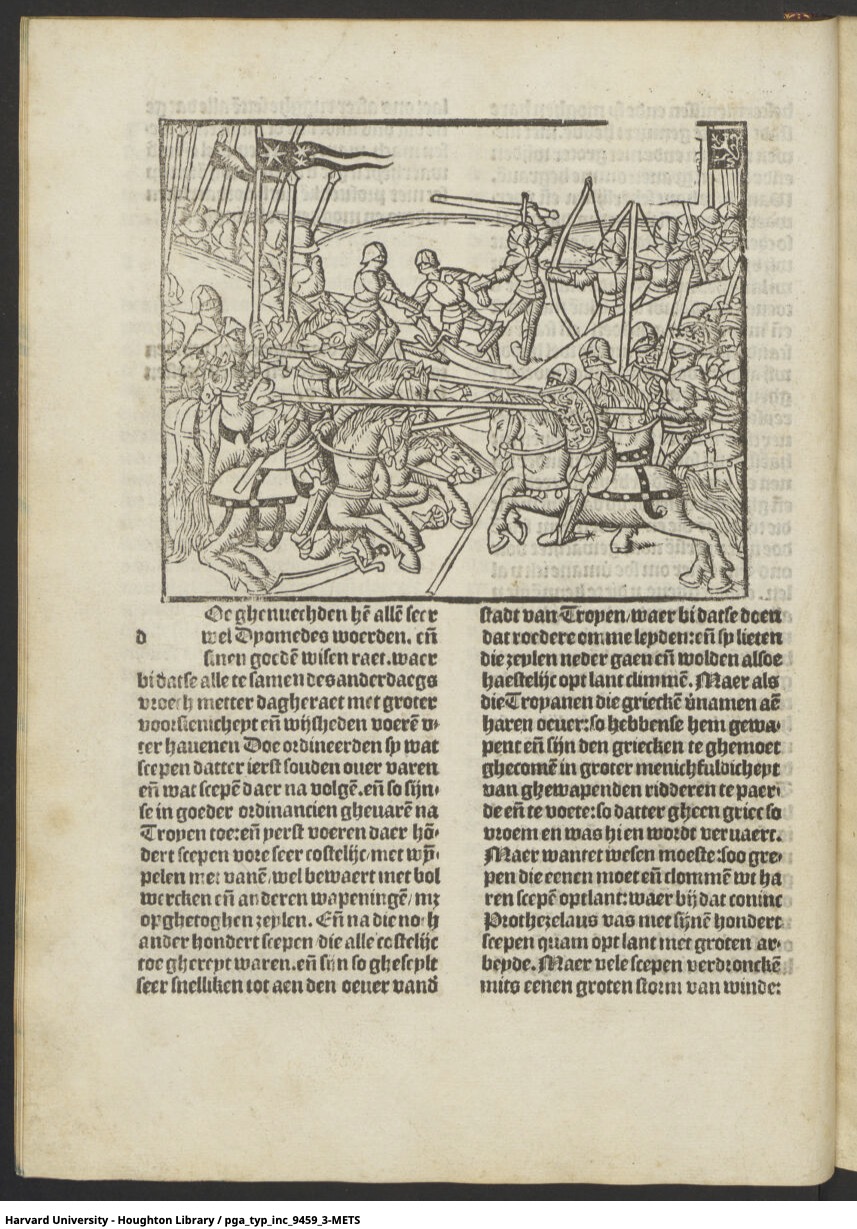

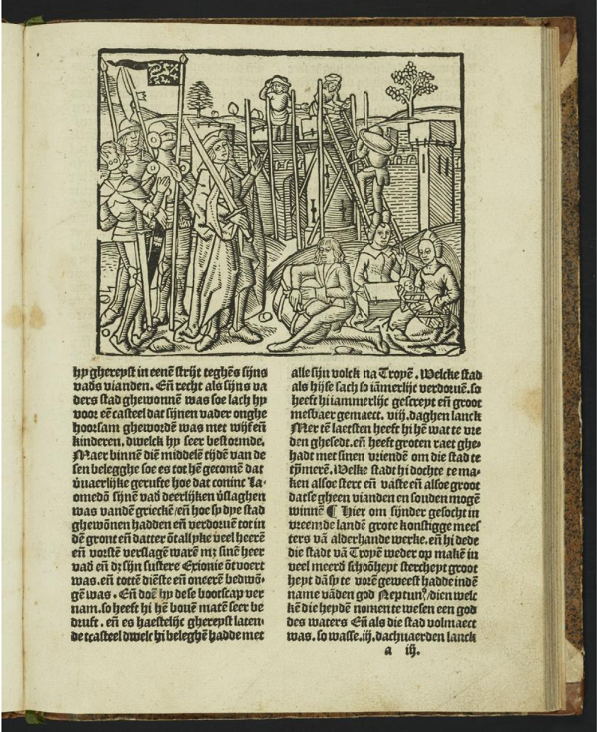

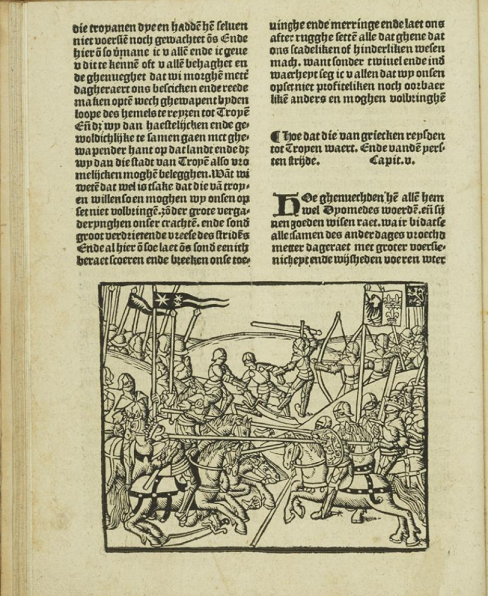

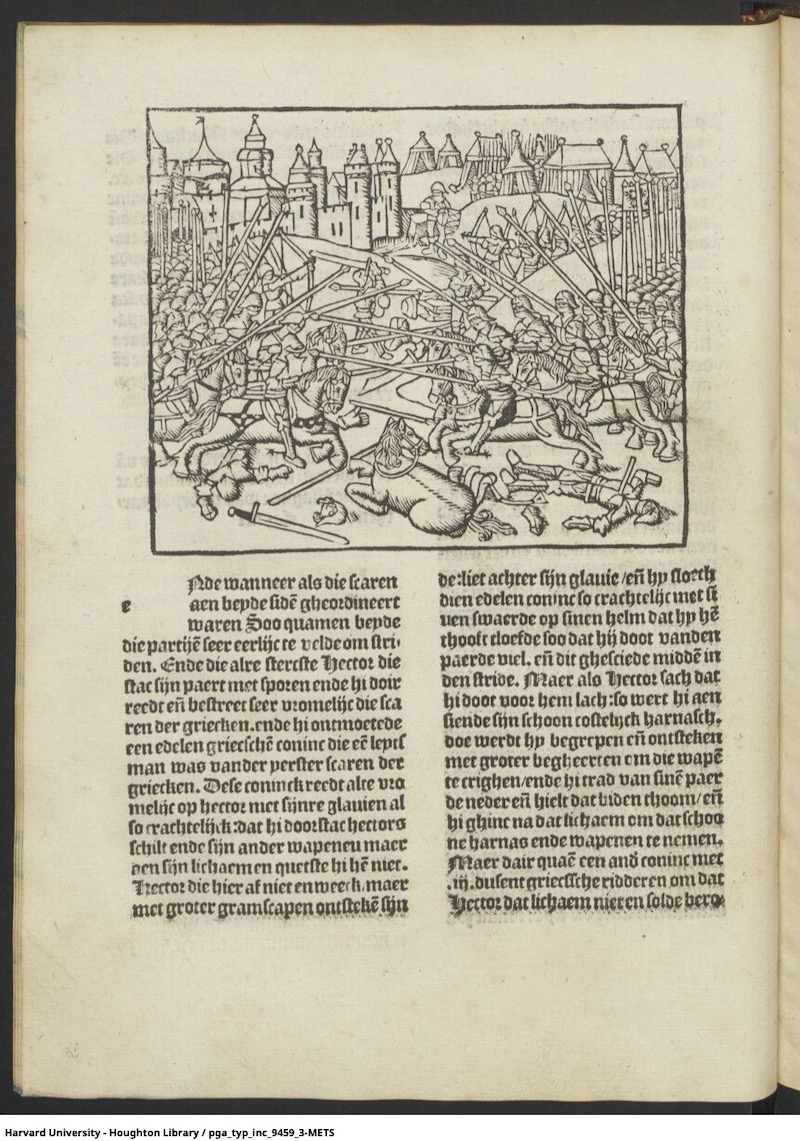

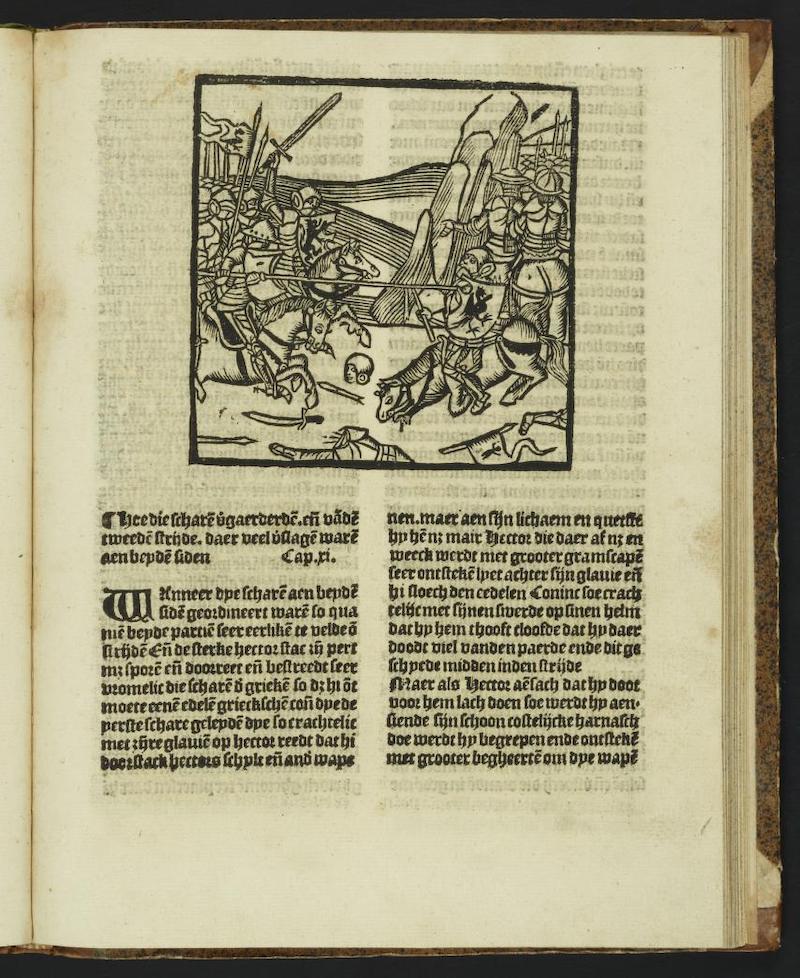

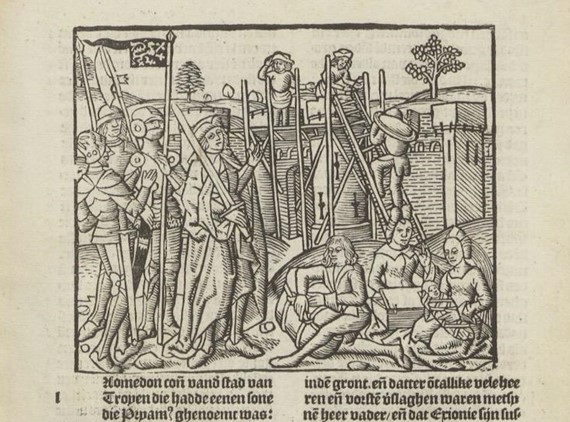

The re-use and copying of woodcuts was a widespread practice during the early period of print. This could be done across different titles, across different editions of a title and within a single edition. Entirely new designs are always rare. Indeed, many designs draw on iconographic conventions that already circulated in manuscripts. Different printers had different strategies of copying and re-use. In re-using generic stock images, these printers were clever in the way they re-used them and favoured images that were particularly suitable for multifunctional use. They also took care that there was, at least, a general thematic or associative relation between image and text.

Various woodcuts are present in some of the editions of the Historia, but what is their meaning? Studies of early-printed books in English and German in particular have demonstrated that images functioned in much more complex ways than as mere decoration. A variety of cases have been identified where common motifs or recurrent images functioned, for example, to highlight interconnections between different texts or text passages, or indeed to challenge readers to create new meanings. These studies have opposed the long-dominant idea that early printers used and re-used woodcut illustrations haphazardly, merely in order to save costs or sell more books. Instead, a more nuanced view has emerged, which holds that the generic visual language of many woodcuts and the re-use of woodblocks need to be interpreted as defining characteristics of early-modern visual culture.

In general, printers used the same stock images for woodcuts. That is why in a number of cases blocks of scholarly half figures, for example, were re-used and copied by and exchanged within a network of printers, including Vorsterman and Roelants, two printers who often re-used Van Doesborch’s half figures. The practice of inserting small, re-usable scholar woodcuts seems to have been initiated by Van Doesborch himself some time before 1520. In the Historia, this practice is visible through two editions in particular, both a Dutch translation of Guido’s work. The first edition is by Rolant van den Dorpe and it is believed to have been printed between 1496 and 1500, while the second one is by his successor, Van Doesborch, and it is dated 1510-1515. In this case, we remark how Van Doesborch uses most of the woodcuts present in Van den Dorpe’s edition, with the exception of a few pages. Despite the editions being ten years apart, the woodcuts appear on the same pages and have the same details.

| Last modified: | 14 July 2024 9.33 p.m. |