1289

In Guido’s Historia the range of characters — most notably the female characters — is much bigger than in Homer’s epic. Although representing a warlike, even chivalrous, and therefore masculine universe, the medieval Trojan War grants a primordial role to women who, although far from the battlefield, are very present and very active behind the scenes of the Trojan palace or the Greek camp. From the complicity of Medea to the sacrifice of Polyxena, the presence of women is therefore continuous, from the beginning to the end of the conflict. The question arises:

What is the role of these women in the Trojan War as told by Guido?

The text tells us the portraits of women often serve the narration and they are characterized by the author praising their beauty, which gives a certain literary aesthetic to his otherwise slightly dry text. In addition, women serve the dramatic plot and, whether they know it or not, they can often restart the action. Finally, through the ideological role of the presence of women, Guido’s misogyny, inherited from late Antiquity and medieval clerics, is clearly expressed in certain portraits of heroines, each being presented as a “new Eve” destined to lose men who are consumed by their passions. The female portraits given in Guido’s Historia therefore fall within these criteria of ideal beauty. In fact, in chapter two (fol. a8r), when Jason tries to seduce Medea to get her help in conquering the Golden Fleece, he praises her great beauty in these terms: "Pulchritudinis prerogativa refulges velut rosa punica, quae veris temporis flores caeteros, quos in arvis campestribus sponte natura produxit, suorum titulorum insigniis antecellit!” (By the privilege of your beauty you shine like a crimson rose that for the marvel of its attributes surpasses the rest of the flowers which nature produces in the fields in springtime!) This famous metaphor of the beautiful, fresh and ruddy woman like a rose is reminiscent of courtly love.

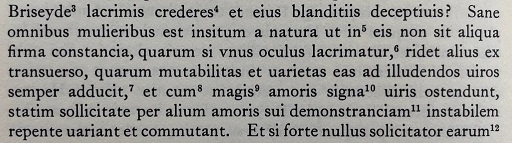

Another particular passage that confirms Guido's misogynistic tendencies has as protagonists Troilus and Briseis, who have a very turbulent history. Troilus is a Trojan prince, the youngest son of King Priam and Queen Hecuba, while Briseis is a captive woman whom Achilles claims as his prize. In some versions of the myth, Troilus falls deeply in love with Briseis, and their relationship becomes a central element of the Trojan War narrative. However, their story ends in tragedy. The Greek hero Achilles, angered by Agamemnon's actions, withdraws from the fighting, leading to a string of Greek defeats. To appease Achilles and convince him to return to battle, the Greek leaders agree to return Briseis to him. This action deeply affects Troilus, who is devastated by the loss of his beloved. In Guido’s Historia, the author puts the blame on Briseis whom he deems as cunning. In doing so, he reproaches Troilus for trusting her. In a scolding tone he says to him: “All women are inconstant; they weep out of one eye and smile out of the other and are ever-changing lovers.” (INC 72, fol. g4r)