Revisiting the Story of Troy

The Historia Destructionis Troiae by Judge Guido delle Colonne of Messina was completed, as its author tells us in his epilogue, in November of 1287. Guido states that it is the authentic history of the Trojan War based upon the eyewitness accounts of Dictys of Crete and Dares the Phrygian. However, as has long been known, it is actually a Latin prose paraphrase, and in many instances a fairly close translation, of the Roman de Troie, a French romance in octosyllabic couplets written more than a hundred years earlier by Benoit de Sainte-Maure. Benoit’s poem, when considered at all, was regarded as only a romanticised version of the full history. Despite this fact, the Historia was immediately accepted for what it intended to be, was widely copied and translated, and did not lose its reputation for authenticity until the eighteenth century, when its supposed sources fell into discredit. Only in the nineteenth century was it shown that Guido used Benoit and that the story had moved from poetry to prose, as well as from romance to history. Today, at least 240 copies of the Historia exist — over seventy are incunabula from the fifteenth century — and one of them, in the Saltykov-Shchedrin Library in St. Petersburg, bears the signatures of the English kings Richard III, James I, and Charles I, as well as the signature of Oliver Cromwell.

Guido’s Historia was the most widely circulated and most influential Troy story in the late Middle Ages. Obviously, the story of Troy does not originate in the Middle Ages, but whereas in the East the homeric epics enjoyed wide circulation, in Western Europe Homer's epics were not known. The Trojan War was the only major classical tale available during the Middle Ages in the form of history. It was particularly popular in Europe because, aside from being a cosmopolitan narrative, it offered a myth of national origins for European cities, regions and nations, and a mirror for aristocratic and princely conduct. The writers of this period, in turning collectively to Trojan stories, helped create an empire of English letters that became the canon of the medieval matter of Troy and, more broadly, English literary history in the later Middle Ages. Because of authors like Dares and Dictys, the events at Troy appeared in a fully rationalized and believable form almost totally devoid of gods and myths. Guido’s Troy story, in addition to being considered factually true, forms a special variety of medieval history that has so far gone unrecognized. Together with his English followers, Guido wrote histories that are neither providential nor nationalistic, but which may be defined as classical chronicles: they report the ancient past with the same eye-witness detail found in late-medieval chronicles of contemporary events.

Did you know?

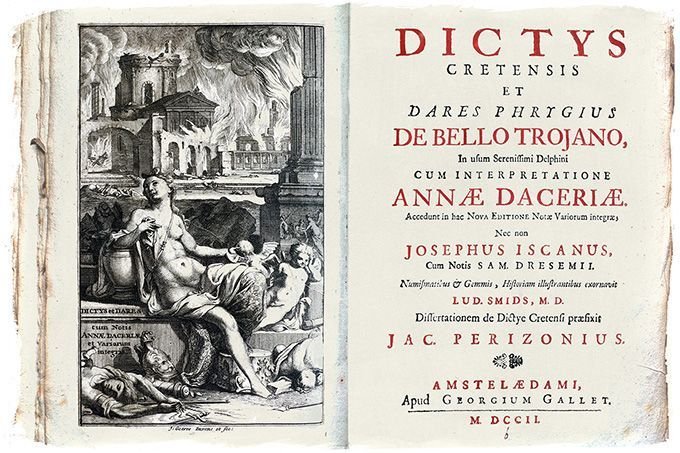

This story consists of an eyewitness account of the Cretan Dictys, who is said to have fought in the Trojan War among the Mycenaeans. His work, which — unlike the Iliad and the Odyssey — does entirely without gods, was central to the way Troy was regarded during the Middle Ages and early-modern times, together with the work of Dares the Phrygian. According to Dictys, it was the Trojans, not the Mycenaeans, who triggered the war, and the Greeks responded by attacking coastal towns in the northwest of Asia Minor (present-day Turkey).

Translations of the Historia Destructionis Troiae

As we have seen, Guido’s tale of Troy, in its various guises, was one of the most widely circulated texts of later medieval Europe. But while the number of existing copies in Latin exceeds two hundred, this should not take away from the Historia’s translations. In fact, Guido’s work was translated or adapted into most European languages including Italian, German, French, Dutch, and Czech. In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, as the art of printing took the whole of Western Europe by storm, in various language areas the vernacular renditions of Guido's Historia were the first to roll off the press. German printers, for example, published an adaptation of the Elsässische Trojabuch as well as Hans Mair’s Buch von Troja in a well-known South-German edition (Bertelsmeier-Kierst). In France, England, and the Low Countries, translations of Raoul Lefèvre’s Histoire de Jason and the Recueil des histoires de Troyes were printed. Whereas Lefèvre’s version of the story remained popular in England, printers in the Low Countries, such as Jan van Doesborch, published modernized adaptations of this narrative.