Reading with the Quill at Hand

Historical annotations, graffiti, doodles, and drawings never cease to intrigue both historians and the public; they speak to a shared human experience that echoes through millennia. From cave paintings to scribbles in school textbooks, it appears we have always wished to make our mark on materials around us. This exhibition focuses specifically on annotations within a manuscript and a printed document that were produced at pivotal moments in the development of Christian scholarship and theology. Whilst they are often thought provoking and charming, an in-depth historical analysis of these marks is frequently lacking.

Whilst the written word was critical in aiding the development of Christian thought, understanding exactly how readers responded to their texts is not always possible when studying merely a book’s textual content. Annotations by their users reveal highly significant information about how readers interacted with these works. By studying these annotations, plus the use of symbols, language and a work’s text layout, we may better understand the interactions that occurred between the “official” text and its readers, giving insights into the reasons for its creation and reception by its audiences at pivotal points of theological change. For this reason, such traces of use are now called “material evidence”.

Misleading Titles

Both the Durham Ritual and Luther Bible have deceptive titles. The Durham Ritual is not a ritual but a collectar, containing the prayers used within the Divine Office, organised according to feast days. Additionally, the Luther Bible was not written by Martin Luther, but is actually a copy of Erasmus’ translation of the New Testament and his accompanying explanations, receiving the name “The Luther Bible” due to the notoriety of its owner. For the sake of clarity and consistency, we will continue to refer to these texts by their “incorrect” titles throughout this exhibition.

Contexts of their Creation

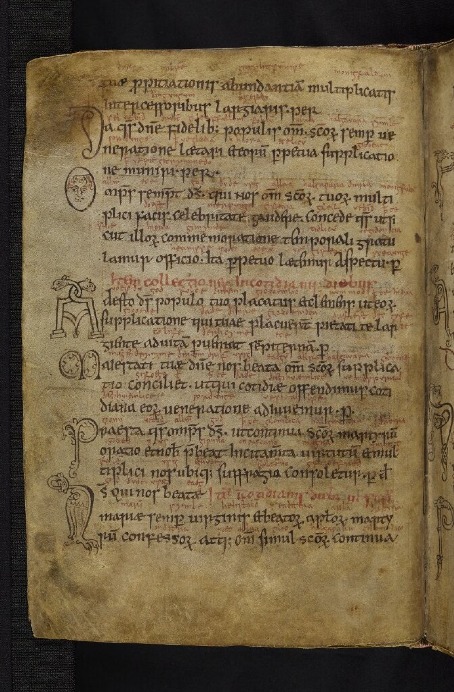

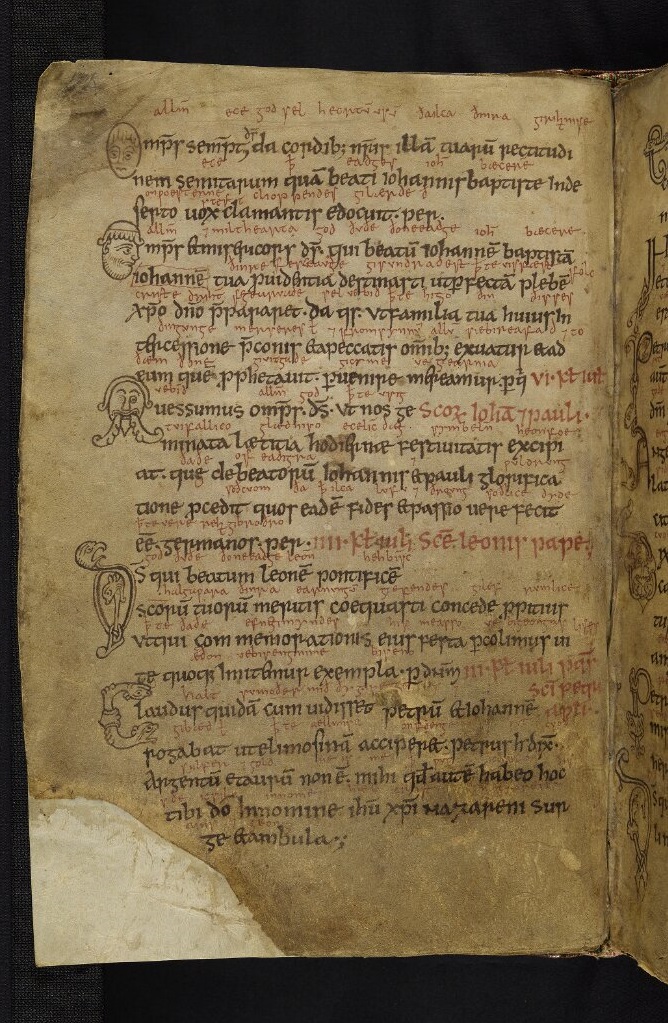

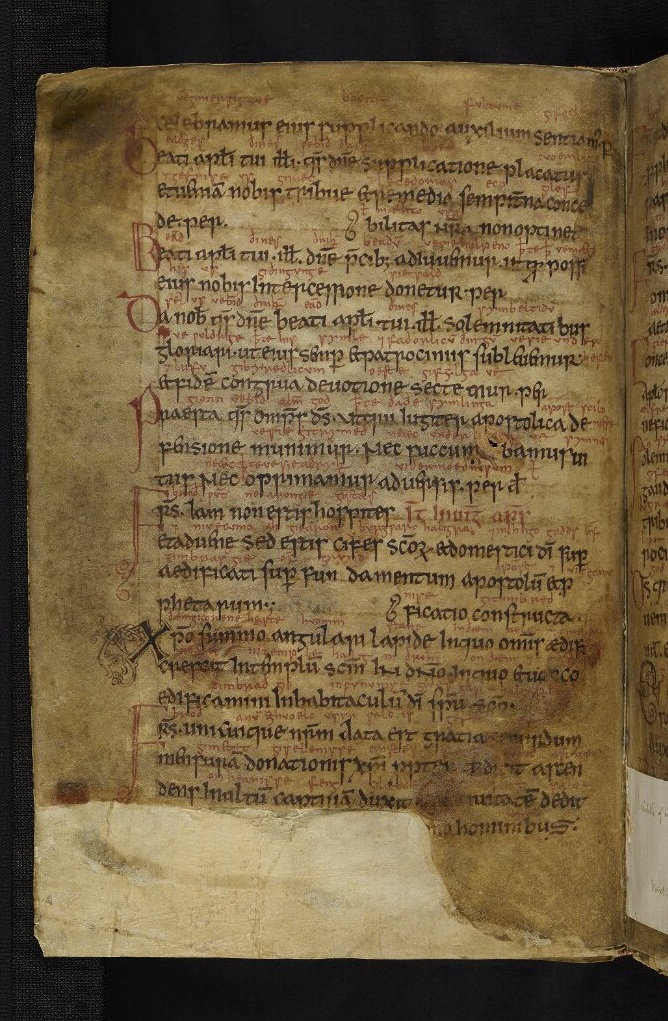

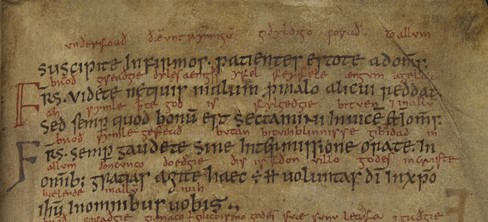

The Durham Ritual (Durham Cathedral Library MS. A.IV.19) is a unique example of a “common-place book” and the oldest example of a collectar in England. Created in the late-ninth to early tenth century in the south of England, it was written initially in Latin, then glossed between the lines into Old English by Alfred the Provost around 60-80 years later. It had an exceptionally long working life, with the text now showing serious wear-and-tear and being incredibly physically fragile as a result. The Ritual was likely copied from an example from Europe, evidenced by the use of a Caroline Minuscule “g” form amidst a text written in Insular Minuscule, and the absence of English saints in the volume. The text was used in the monastic community of Saint Cuthbert on Lindisfarne, one of the most influential Christian sites in the North East of England.

The emotional value of the manuscript to its community is demonstrated by the Lindisfarne community’s choice to take the book (along with the body of Saint Cuthbert) from Lindisfarne to Durham after Viking attacks on the monastery on the Northumbrian coast. This document is thus a highly important one for understanding the importance of long-distance communication and European influence on Anglo-Saxon Christianity, and how religious communities coped when under severe pressure.

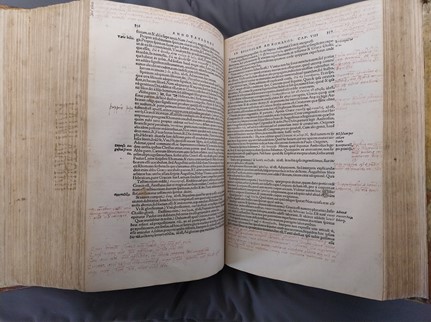

The Luther Bible is a copy of a Latin translation of the New Testament made by Erasmus of Rotterdam, printed by his close friend Johannes Froben at Basel in 1527. This fourth edition of Erasmus’ Novum Testamentum was the first printed edition in which next to a Greek text of the New Testament and Erasmus’ own Latin translation the widely used Vulgate translation of St. Jerome from the late-fourth century was provided. By placing his new work alongside the Greek and the Vulgate Latin, Erasmus wanted to present his own translation as the more accurate and more complete translation of God’s word in comparison to the ‘official’ Vulgate translation.

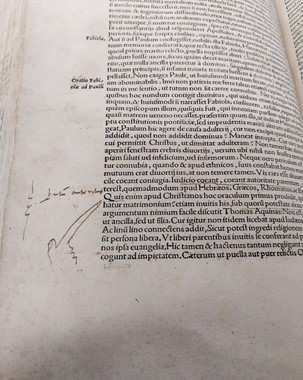

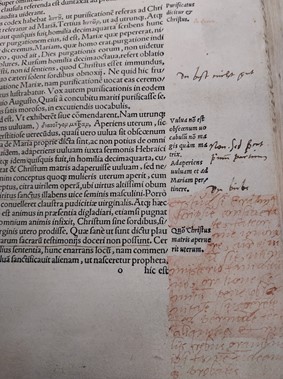

As mentioned, this copy of the Novum Testamentum became the ‘Luther Bible’ not because Luther wrote the book, but because he wrote in it. Both Luther and Erasmus were critics of the catholic Church, but Luther’s annotations demonstrate he was highly sceptical of the intellectual enterprise which Erasmus had undertaken in his Novum Testamentum. It is important to note that Luther was not the only one to annotate the book. The annotations of Regnerus Praedinius (1510-1559), rector of the Latin School in the city of Groningen, are in fact the most extensive ones in the Luther Bible. His elaborate annotations in red ink contrast sharply with the short and simple annotations made by Luther. Luther and Praedinius annotated the work in their own style, but both men felt compelled to add to the work out of a deep emotional response to the (added) content.

Reading Assistance

Studying a text’s layout, decoration, and annotation can help reveal the reasons for a manuscript’s initial creation. For example, the Durham Ritual is set out in a style known as “per cola et commata”, which uses a new line for each new sentence. This was designed to assist with the first stage of the reading process, reading the text aloud, considered a far more integral part of the reading process than it is today. This was followed by contemplation of the text, during which the word of God would be revealed to the reader. The oral use of the text was further assisted by the decorated, rubricated initials at the beginning of each new sentence, decorated with beasts, men and geometric patterns, executed by a highly competent scribe. The use of illustrated initials would continue well into the medieval and early modern periods, where they would become increasingly elaborate. Stylistically, these initials illustrate the cultural connections between the community of Saint Cuthbert, Ireland, Pictland and the rest of Christian Europe, but their humorousness and simplicity are charming in their own right.

The annotations and symbols used by the readers of the Luther Bible differ significantly from those of the Anglo-Saxon period, but their purpose, to aid with the reading and study of the text, remained just as important. However, symbols in early modern texts are often not added by the producers of the book. Instead, books were printed with large margins, to allow space for different kinds of reading assistance that had to be created by the readers themselves via annotation.

A typical early modern reading aid is the practice of drawing a pointing finger (also known as manicula or index) next to passages which the reader deemed important. Leafing through a book in order to find specific passages became a lot easier when people only had to look for these kinds of symbols. Since we tend to remember images better than mere words, the pointing finger helped in the memorisation of important passages. Another typical phenomenon was early modern readers using flowerlike icons in order to connect certain written lines in the margin to specific parts in the text. This practice resembles modern methods of annotation that we might use to aid our own studies. Although nowadays the flowerlike symbols have been substituted by numbers or asterisks, the use of such symbols remains the same: elaborating on or providing references for a specific part of the text.

Errors, Real and Perceived

The Durham Ritual is littered with mistakes throughout; whilst it was written by a highly trained scribe, the quality of Latin is very poor. The Christian religion in Northumbria was coming out of a time of crisis after the decimation of monastic houses, scholars, and their libraries caused by Viking attacks on the region. As a result, the level of Latinity in the Durham Ritual is very low, with seven instances where male saints’ genders are inaccurate, fourteen instances where the scribe cannot form the genitive and eight instances where the date of a feast is recorded incorrectly. Yet, the text was used for at least a century in one of the most prominent and important centres of Christianity in England, and as such, these mistakes provide a valuable insight into both the intellectual and physical health of the Christian religion in this period.

As a result of numerous Viking raids in the ninth century, monastic houses (and their libraries) suffered serious attacks, especially in the north of England. Manuscript production was effectively halted in England in the 860s, not to be revived until the end of the century. Consequently, the number of appropriately educated Latin scholars in Anglo-Saxon England was so low that Alfred the Great deemed it necessary for important surviving texts to be glossed into Old English. In his preface to his translation of Gregory the Great’s Pastoral Care, Alfred laments:

“So completely had wisdom fallen off in England that there were very few on this side of the Humber who could understand their ritual in English, or indeed could translate a letter from Latin into English; and I believe that there were not many beyond the Humber.”

It is clear that the level of Latinity and number of scholars in England had declined significantly and gave Alfred cause for concern, despite his possible exaggerations. Translation of the texts that were “most necessary for all men to know” would keep them accessible for a new generation of English scholars, regardless of their ability to read and write Latin. The Durham Ritual was not only glossed, but was taken with the community of Saint Cuthbert during their move from Lindisfarne to Durham, despite its numerous mistakes and inaccuracies. This demonstrates the importance the text must have held within its community in the wake of Viking attacks on their home.

Whilst the Groningen Luther Bible is not free of errors, Luther’s annotations demonstrate that he perceived the entirety of Erasmus’ new translation of the Novum Testamentum as erroneous. Luther’s annotations in Erasmus’ Annotationes reveal him to be a highly critical reader who had little patience for intellectual approaches that differed from his own. They show that Luther regarded Erasmus as a complacent intellectual with no respect for the authority and the holiness of the Bible. Annotations such as “nihil” and “du bist nicht gut” and “du bist ein bube/du bube” (“nothing” and “you are not good”, and “you are a scoundrel”) show Luther’s antipathy and his angry emotional response to Erasmus’ work.

This anger may even be visible on the book’s pages. The nineteenth-century theologian C.P. Hofstede de Groot remarked that the ink marks on pages opposite to those with the angriest notes demonstrate that Luther may have slammed the book closed without even waiting for the ink to dry, as if he could not bear to read the words any longer. Although the Luther Bible has multiple annotations on pages which left marks on the opposite page and Luther could have closed the book for other reasons, this interpretation certainly creates a vivid image of Luther’s frustration.

Luther’s commentary provoked additional annotations from a later reader of the Novum Testamentum. Regnerus Praedinius, who owned the book after Luther and was an outspoken admirer of Erasmus, felt compelled to write multiple annotations in response to Luther’s to clear the name of his idol. Praedinius clearly felt Luther's statements could not be ignored, and his remarks demonstrate the urgency he must have felt in responding to commentary that he perceived as unjust or untruthful.

The Texts Today: Accessibility and Digitisation

Humans have always felt a need to make their own mark on the world around them. Both the Groningen Luther Bible and the Durham Ritual illustrate the ways in which scholars used annotation in the past to respond to their own changing worlds, whether that be as a result of Viking raids or theological developments that would change the course of Christianity in the Western world forever.

Until the twentieth century, interaction with the Durham Ritual and Luther Bible was restricted to scholars and conservators, but many historical documents have now been made accessible to the global public as a result of the advancement of digitisation. This is a critical advance in academia, allowing students, researchers and the curious public to access highly fragile texts which are sometimes nearly inaccessible even to scholars in a controlled reading room. This is especially the case for the Durham Ritual, which experienced significant damage over its period of use. Furthermore, digitisation has opened new possibilities for interaction, not just with the textual content of these books, but also with the markings and inscriptions their former owners left behind.

Explore the Durham Ritual and the Luther Bible yourself:

-

Durham Ritual (Cathedral Library MS. A.IV.19 - The Durham Ritual)

-

Groningen Luther Bible (HS 494 1 Novum Testamentum ex Erasmi Roterodami recognitione)

-

Groningen Luther Bible (HS 494 2 Des. Erasmi Roterodami In Novum Testamentum Annotationes)

Further Reading

-

Bogaert, P.M. “The Latin Bible c. 600 to c. 900.” In The New Cambridge History of the Bible. Volume 2, From 600-1450, edited by R. Marsden and E.A. Matter, 69-92. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

-

Correa, A. The Durham Collectar. London: Henry Bradshaw Society, 1992.

-

Gameson, R and A.I. Doyle. Manuscript Treasures of Durham Cathedral. London: Third Millennium, 2010.

-

Kingma, J. De Groningse Luther-Bijbel: Tentoonstelling rond Luthers exemplaar van Erasmus’ Nieuwe Testament, Basel 1527, 3 november – 23 december 1983. Groningen: Universiteitsbibliotheek Groningen, 1983.

-

Lindelöf, U. “A New Collation of the Gloss of the Durham Ritual.” The Modern Language Review 18:3 (1923): 273-280.

-

Sherman, W.H. Used Books: Marking Readers in Renaissance England. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008.

-

Visser. A. “Erasmus, Luther and the Margins of Biblical Misunderstanding.” In For the Sake of Learning: Essays in Honor of Anthony Grafton, edited by A. Blair and A-S. Goeing, 232-250. Leiden: Brill, 2016.

-

Visser. A. “Irreverent Reading: Martin Luther as Annotator of Erasmus.” The Sixteenth Century Journal 48:1 (2017): 87-109.

-

Westra, M. and I. Loois. “Erasmus & Luther in Frisia.” Website Stories of Frisia

This exhibition was made as part of the Summer School Things That Matter 2023.