The Wittewierum Library

The Wittewierum Library is a thing of the past. For centuries now. It only existed as long as there was an abbey there. In 1561, that abbey Hortus Floridus (Flowery Garden) was dissolved. Its assets were taken over by the newly instituted Bishop of Groningen. Its last remains vanished in the 19th century.

How do we know the abbey had a library? “An abbey without a library is like an army camp without an arsenal.” This medieval saying makes it probable, to begin with. So does common sense. Monks wanted, and were obligated, to read the Bible and other sacred writings. These had to be available, then, and not everyone could afford to have his own books, which were quite expensive.

Hard evidence is the fact that the library at Wittewierum is explicitly mentioned in the abbey’s Chronicle, which we treasure in Groningen as part of our Special Collections. We read: (fol. 32v) “Abbot Emo devoted himself to stacking the library in the chapter room with the books of Holy Scripture ... By reading, emending, and inserting useful annotations he left traces of his hand in nearly all the books in the library.” (ill. 2) We also read that Emo copied books himself, urged his monks to do so, and even trained ‘suitable women’ to copy texts.

Undoubtedly, abbot Emo himself contributed substantially to the abbey’s library. In the abbey’s Chronicle, he and his successor Menko quote many authors on a variety of topics. Emo copied books during his entire life and he was a frequent traveller, which will have enabled him to gather many books. There was every need for books, since the abbey quickly grew into a large one. In 1289, there was a census of the Premonstratensian monasteries at Wittewierum (monks) and Jukwerd (nuns). They counted up to a thousand people. While this will have included all ‘personnel’, it shows that the abbey’s library served many readers.

The Wittewierum Library must have counted many books, then. Unfortunately, next to nothing seems to be left. In 1515, the abbey suffered a large fire which few books will have survived. Those that did perished over the next five centuries or became dispersed throughout the world, and thus disappeared. The only two manuscripts from Flowery Garden known to have survived are Emo and Menko’s chronicle of the abbey and a summarizing copy of that chronicle with some new additions. We cherish both in the University of Groningen Library.

Have more books from Flowery Garden survived the test of time? If so, we can only know by inspecting books in collections all over the world to see if they contain any handwritten notes linking them to the abbey at Wittewierum. As a result so far, two more books from the abbey have reappeared. They’re even reunited, almost, for both are now at The Hague.

The Royal Library of the Netherlands has a copy of the collected works of the church father Cyprian edited by Erasmus of Rotterdam and published at Basel in 1521. The book contains this handwritten statement: “I belong to Cornelius Hermanni, formerly abbot at Wittewierum.”

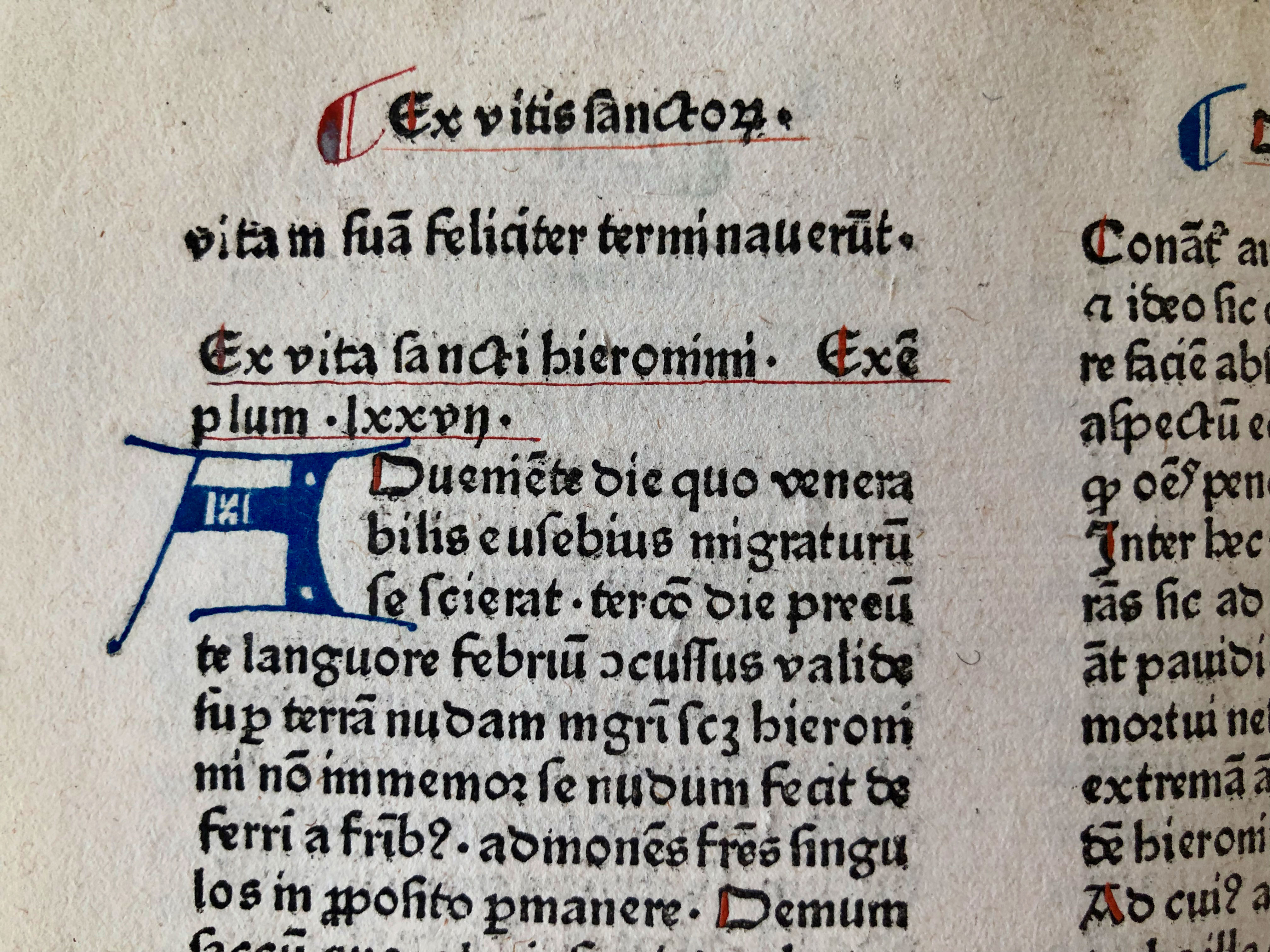

Less than a mile away, we find the House of Books alias Museum Meermanno-Westreenianum. Among its books is a pretty incunable that once lay in Wittewierum. (Recently, this was registered in Material Evidence in Incunabula—in Dutch only, remarkably.) It concerns an edition of Speculum exemplorum printed by Richard Pafraet at Deventer in 1481. (ill. 3) Its contents eminently suit an abbey, for it is filled with edifying as well as entertaining stories about exemplary Christian behaviour. A full thousand pages.

Its contemporary binding consists of oakwood boards covered with brown leather with blindtooled decorations. On the front cover, the decoration takes the form of straight lines and diamonds as well as little stamps of flowers and birds; the back cover lacks the stamps. (ill. 4) The covers still have clasp catches, but the clasps are now lacking. At the upper end of the front cover, we still see four little nails that once held down a title window (fenestra). (ill. 5)

Bound with the book is a strip of parchment on which is written in a contemporary hand: “Book of the friars of the Premonstratensian order in Wierum alias in Flowery Garden.” (ill.1) The first leaf of the edition contains no printed text. Instead, the first page contains a handwritten note stating that the book is owned by the Cathedral Chapter in Groningen (i.e. St. Martin’s Church) from the legacy of abbot Cornelius Hermanni. (ill. 6)

As is often the case with incunables, this copy is made unique by the elements and decorations that were added to it manually in post-production. Throughout the book, initials were added with red or bright blue paint. (ill. 7) One single time, an initial was added and richly illuminated in three colours—on fol. a2r, where the book’s main text begins. (ill. 8)

Another remarkable feature are the handwritten additions to a strikingly small part of the book. At fol. 2h6v, someone began phrasing the topics of the paragraphs into which the printed text is divided. (ill. 9 ) He stopped doing so at fol. 2k3r, a mere twenty-five pages on. Nor did he do so for every single paragraph in this section. His very first phrase (De elemosina danda or On giving alms) is written in the margin, all the rest between the printed lines.

Whoever wrote these notes remains unidentified, but he wrote in a neat hand. On fol. 3a2v (at distinctio 9:123), he added a solitary note to inform readers that they can find more examples concerning the Virgin Mary in a previous part of the book: “Quere plura exempla de beata virgine Maria in distinctione sexta capitulo LX.” (ill. 10)

A final feature are the gorgeous bookmarks by way of tiny spheres made of purple leather which were attached to paper strips that were then glued to the edge of a page. (ill. 11) This resulted in a series of rotund bookmarks at the side of the book which made opening the book quickly a lot easier. (ill. 12) Experience, or knowledge, taught the monks which sphere to choose in each instance.

I would gladly reunite both printed books with their manuscript siblings from Wittewierum, and preserve them together with the other witnesses to Groningen’s rich monastic past in our Special Collections. That won’t happen, of course, and perhaps rightly so. At any rate, more books from Wittewierum may well resurface, and perhaps we’ll be able to acquire those. Seek, and ye shall find.

With many thanks to Jos van Heel (olim MMW), who alerted me to this incunable, and to Petra Luijkx (MMW), who enabled me to inspect it closely.

Sources

- Kroniek van het klooster Bloemhof te Wittewierum. Inleiding, editie en vertaling H.P.H. Jansen & A. Janse (Hilversum 1991)

- De wereld aan boeken. Een keuze uit de collectie van de Groningse Universiteitsbibliotheek (Groningen 1987)

- University of Groningen Library, Special Collections, Archive of prof. dr. Jos.M.M. Hermans (typoscript of his dissertation, 1987, par. 2.2.1.13: Wittewierum, Bloemkamp)

- Het middeleeuwse boek in Groningen. Verkenningen rond fragmenten van handschrift en druk, ed. Jos.M.M. Hermans (Groningen 1981²)

- Historie van Groningen. Stad en Land, ed. W.J. Formsma et al. (Groningen 1976)

- T. Gerits, “Boekenbezit en boekengebruik in de middeleeuwse Premonstratenzerabdijen van de Nederlanden” in: Studies over het Boekenbezit en Boekengebruik in de Nederlanden vóór 1600 (Brussels 1974), pp. 79-157