Brecht’s Book of Hours, One of a Kind

Bargain hunting is a favourite hobby of mine. While strolling a garage sale, I secretly hope to find, between the moulded penguinpockets and the worn romance novels, a precious book that has gone unnoticed.

So I can well imagine it must have been a special experience for the lady who in 1986 brought a small handwritten book to the experts of the television programme Tussen Kunst en Kitsch, which is some sort of Dutch version of Cash in the Attic. She was told her book was a unique book of hours dating back to the late-15th century! A book of hours is a book containing a collection of prayers to be used by lay Christians for personal devotion. These prayers were said at set hours of the day, hence the name. The lady in question was determined to stay anonymous. She kept away from the camera’s and didn’t answer a public call by experts (after the programme had been televised) to contact them privately. Among these experts was professor Jos Hermans (1949-2007), a medievalist, book historian, and codicologist in the University of Groningen. After nearly four decades, however, this changed. Having reached a high age, the lady decided to donate her treasure to a public institution in order to guarantee its preservation. Now it is owned by the University of Groningen Library.

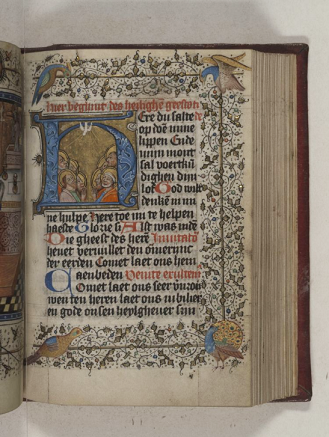

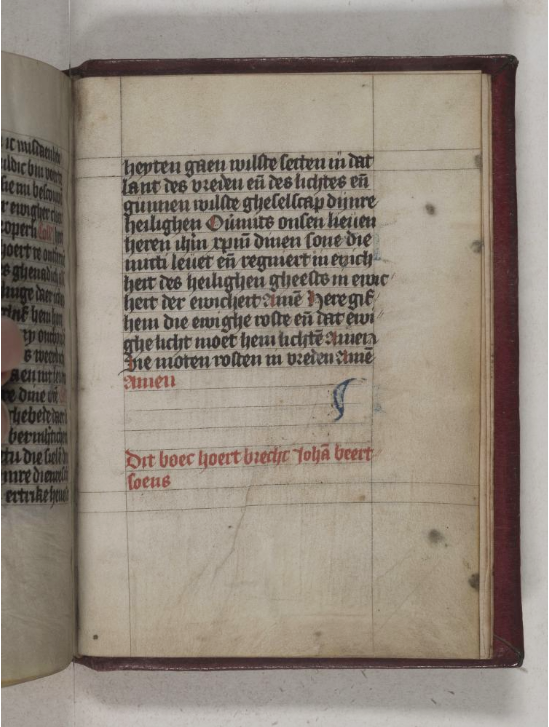

Around 1480, the book was owned by ‘Brecht Johan Beert soens’ – as is stated on its final leaf. This means: Brecht, wife of Johan, son of Beert. This is all we know about her. By means of this book, Brecht could say and ponder the various prayers contained in it. These are written in Middle Dutch, the vernacular of the time in the Low Countries. They are the Hours of the Virgin Mary, the Hours of the Holy Cross, the Hours of the Eternal Wisdom, the Hours of the Holy Spirit, the Seven Penitential Psalms, two Sacrament Prayers, and the Vigil of the Dead. Originally written in Latin, these texts had been translated into Dutch by the theologian and church reformer Geert Grote of Deventer (1340-1384). He did so, because he wanted common people to have access to these texts, too, instead of them being read exclusively by the clerics of the Catholic Church, who were all versed in Latin. Grote’s vernacular prayers were bestsellers in the Low Countries of the later Middle Ages.

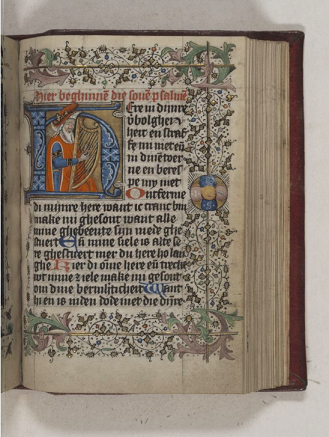

In our book of hours, all prayers start with a gorgeous, page-sized, colourful miniature (painting) and a historiated initial, so a capital first letter in which a scene befitting the subsequent text is painted. Sadly, the leaves containing the miniature and the historiated initial at the beginning of the Hours of the Virgin Mary and the Vigil of the Dead (which was read by a wake for a deceased person) are now lacking, because at some point these leaves have been cut out. However, a clue as to how they might have looked is given by a sister manuscript which recently turned up at a Parisian art dealer. The contents and illumination (decoration) of that manuscript bear a striking resemblance to Brecht’s book of hours.

The Hours of the Virgin Mary in the Parisian book of hours open with a miniature of the Annunciation of Christ’s birth, traditionally showing Mary and the angel Gabriel. The Vigil of the Dead has an opening miniature showing the souls in Abraham’s lap. This image refers to the biblical story of Lazarus and the rich man in which only the former is allowed to wait for the end of time in Abraham’s lap. It is very probable that Brecht’s book also contained these two images.

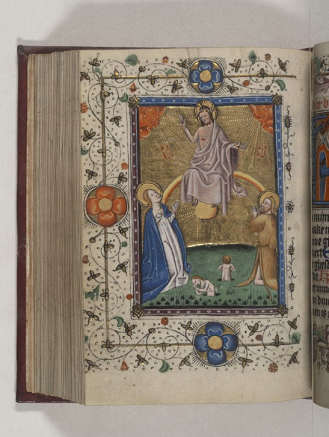

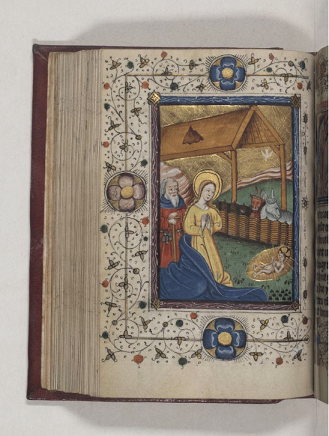

Another remarkable likeness between these two books of hours concerns the miniature preceding the Hours of the Eternal Wisdom. The central theme of this prayer is the divine power that can inspire the faithful to a religious life. The artist painted a nativity scene featuring Joseph, Mary, and the infant Jesus in the manger, with the ox and the donkey as spectators. This combination of text and image is inexplicable, but it must have been a deliberate choice, since it occurs in both books of hours.

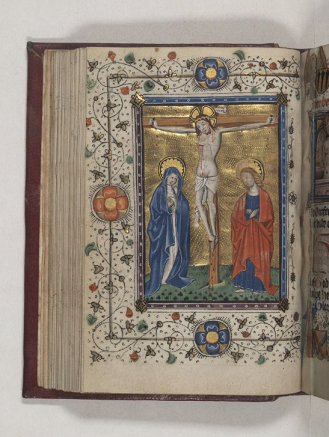

Brecht’s book also has similarities to the so-called Sarijs Manuscripts. This is a group of late-medieval manuscripts produced in the eastern Low Countries. They derive their name from a scribal error in the calendar that invariably precedes the texts in these books of hours. January 19 is the feast day of S(aint) Marijs, but at some stage a scribe erroneously wrote Sarijs and this error was copied many times, thus characterizing a group of books of hours with a shared provenance. This error also occurs in Brecht’s book, which shares quite a few miniatures with other Sarijs Manuscripts, too. For example, at the beginning of the Hours of the Cross we see a crucified Christ and two prominent witnesses, his mother Mary and his beloved disciple John. The accompanying historiated initial also contains an image of a suffering Christ.

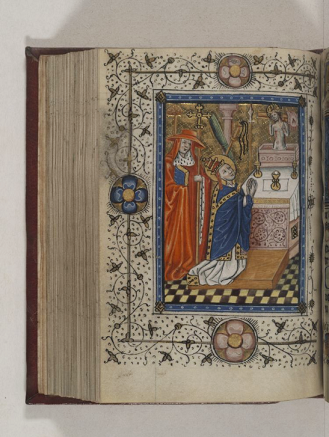

Despite such similarities to other manuscripts Brecht’s book of hours is still one of a kind. It’s fascinating to discover how the miniaturist or composer of this book made certain peculiar choices. Why does a miniature of Pope Gregory saying Mass accompany the Hours of the Holy Spirit? The initial here makes more sense, as it shows Jesus’s apostles looking up to heaven while a dove (representing the Holy Spirit) is descending upon them. Also peculiar is the initial starting the Penitential Psalms: we see King David playing the harp instead of him repenting his adultery with Bathsheba, an illustration typically found with these Psalms in Sarijs Manuscripts.

It has long been thought that books of hours were illuminated by nuns in convents. Recent studies, however, show that a great many artisans (scribes, penwork drawers, book painters) must have been involved in the production of such books, and that these artisans lived and worked independently in the towns. In the case of Brecht’s book and the Sarijs Manuscripts, it was the town of Zwolle in the northeast of the Low Countries, as is confirmed by the fact that the texts are written in a dialect characteristic of that region.

Although Brecht’s book has now been digitized, it is still possible to come to the Special Collections Reading Room in the UB and leaf through its parchment pages. Thanks to its previous owner, who shall remain anonymous, it is no longer hidden in private, but now publically available for teaching and research, or simply enjoyment.