Let’s get rid of those inconvenient food diaries for diabetes patients

Patients who run the risk of developing diabetes are often asked to keep a diary of everything they eat. Elisabeth Wilhelm, assistant professor of Control of Robotic Systems at the University of Groningen, is working on a digital app that gives these patients direct insight into their eating habits and their lifestyle as a whole. ‘If we think carefully about our diet, type 2 diabetes can be reduced at an early stage,’ Wilhelm explains.

FSE Science Newsroom | Text Charlotte Vlek | Images Leoni von Ristok

‘A chocolate bar tastes good now, but we often don’t think about how it’s going to help us healthily reach sixty,’ Wilhelm says. But every intake of sugar leads to a rising glucose level in the blood, to which the body needs to respond by making insulin. In type 2 diabetes, the body develops an insensitivity to insulin and is not producing enough of it.

Onze app zal niet gewoon zeggen: eet minder suiker.

The app that Wilhelm wants to develop, will give users insight into the effects of their lifestyle. To this end, she is collaborating with Claudine Lamoth, Professor of Movement Analysis & Smart Technology in Aging at the UMCG, and Hilbrand Oldenhuis, lector of Digital Health at the Hanze University of Applied Sciences. Wilhelm explains: ‘Our app will not just say: eat less sugar. What you eat matters, but so does your sleeping pattern and how much exercise you get.’ The interplay between these factors is complex and differs per individual, which makes it a huge advantage to get individual feedback via an app.

A question from medical practice

The idea to develop such an app originated from another project: Healthy living as a service. Wilhelm: ‘Doctors told us that there’s no easy way to monitor what a patient eats. Yes, they track their own food intake in a diary, and there are some handy apps to help them, but just try to do this when going out to dinner! Or when sharing a bag of crisps with your friends. Sometimes, it just happens that this bag of crisps is suddenly empty, and of course, you were not the one who ate them all.’

A full box of popsicles

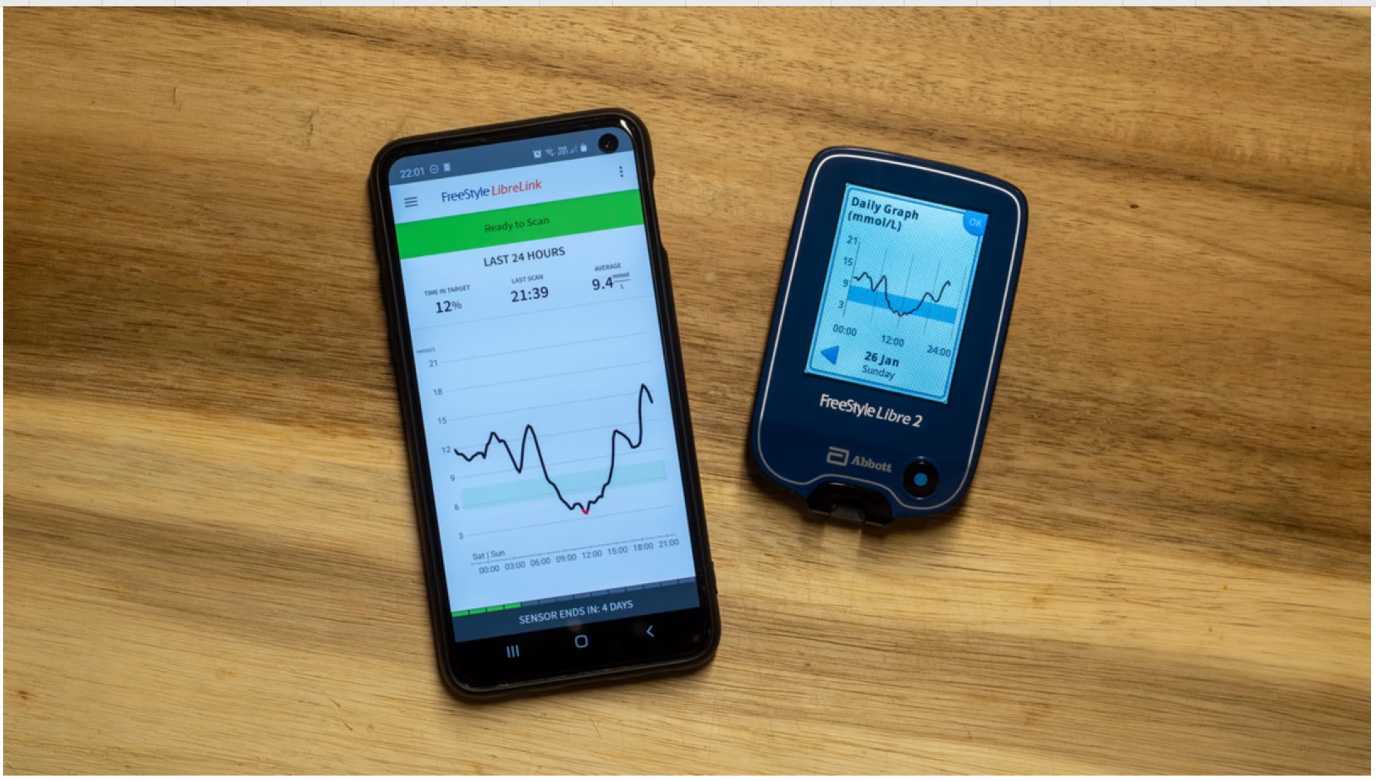

The first step for Wilhelm was to directly read eating habits from a sensor, allowing patients to skip the complicated task of keeping a diary. While sensors that measure glucose levels in the blood already exist, they are meant to be used by diabetes patients to monitor their insulin needs. Whether these sensors are suitable for healthy participants, however, was not clear.

That is why PhD student Linda Ong asked participants to eat whatever they wanted for one week while keeping an ‘old-fashioned’ food diary. She also checked their glucose levels with a sensor and managed to connect the two: she found a moderate correlation between the sensor measurements and the diary. That was enough for Wilhelm to be able to continue with this project. In the next phase, more participants of various age groups will be tested.

But for now, an anecdotal indication says it all, Ong reports: ‘Someone had filled in in their food diary that they had a full box of popsicles, while we couldn’t see it in their glucose levels. They probably forgot to fill in the right portion size in their diary and most likely had just one popsicle from the box.’

Know what you eat

Of course, it is impossible to determine exactly what someone ate from their blood levels—whether it was a Mars bar or a Twix bar we’ll never know. However, Ong successfully recognized in the blood values whether someone had consumed food with high, moderate, or low sugar content. More specifically, she was able to estimate the glycemic load, as recorded in the diary.

The glycemic load depends on both what kind of food you eat—a sweet snack that causes a high glucose peak in the blood or wholewheat bread with a lot of fibre that causes a slower uptake—and how much of it you eat. However, determining this glycemic load based on just the measurements of the sensor is not straightforward.

‘All participants had their own lifestyle, with their own sleeping patterns and exercise preferences,’ Ong says. And all these things influence how what you eat ends up in the blood. However, by using smart mathematical techniques to look at how fast the values change and how much the blood sugar level increases after eating, it was still possible to estimate the glycemic load.

So that people actually use it

Ong’s results pave the way for the development of a new app, that can give feedback on other lifestyle choices besides eating habits. To this end, Wilhelm will collaborate with the Hanze University of Applied Sciences. Wilhelm: ‘One of their PhD students will work on the design of the app, and on how to best bring its message to the users. Because, of course, we want this app to be something that people will actually use.’

This research project is part of the Health Technology Research and Innovation Cluster (HTRIC). HTRIC brings scientific technology to the medical practice. Next week, read more about another topic from HTRIC, tackling the number one cause of death in the intensive care unit.

| Published on: | 05 December 2024 |

Sepsis is the number one cause of death in the intensive care unit. The difficulty with sepsis is that the symptoms vary greatly, which means it is difficult to diagnose in time. Geert van den Bogaart collaborates with the University Medical Center Groningen (UMCG) on a method for the early detection of sepsis.

| Last modified: | 05 December 2024 4.07 p.m. |

More news

-

03 April 2025

IMChip and MimeCure in top 10 of the national Academic Startup Competition

Prof. Tamalika Banerjee’s startup IMChip and Prof. Erik Frijlink and Dr. Luke van der Koog’s startup MimeCure have made it into the top 10 of the national Academic Startup Competition.

-

01 April 2025

NSC’s electoral reform plan may have unwanted consequences

The new voting system, proposed by minister Uitermark, could jeopardize the fundamental principle of proportional representation, says Davide Grossi, Professor of Collective Decision Making and Computation at the University of Groningen

-

01 April 2025

'Diversity leads to better science'

In addition to her biological research on ageing, Hannah Dugdale also studies disparities relating to diversity in science. Thanks to the latter, she is one of the two 2024 laureates of the Athena Award, an NWO prize for successful and inspiring...