NSC’s electoral reform plan may have unwanted consequences

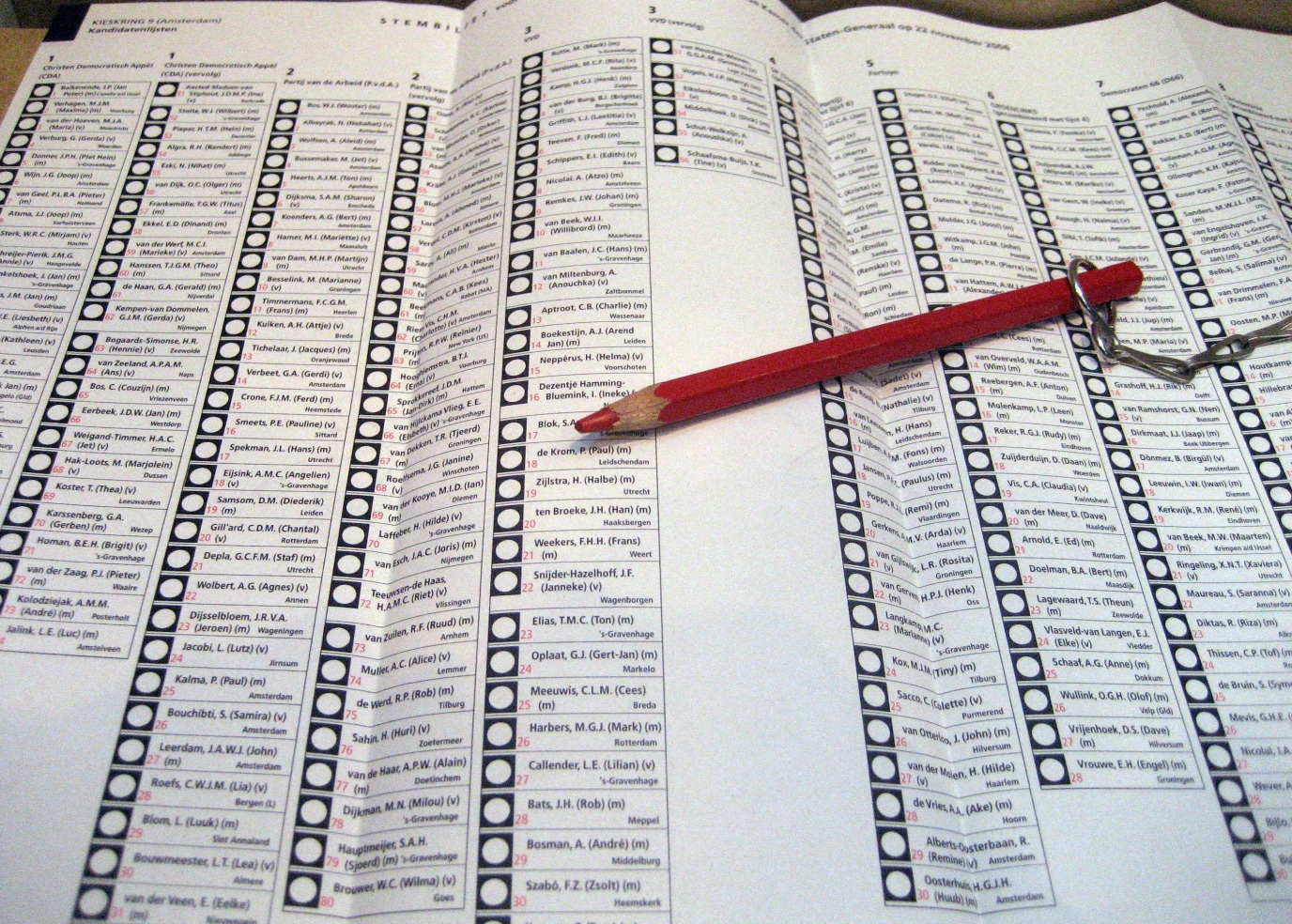

Minister Uitermark (NSC) wants to introduce a new voting system in the Netherlands: the Parliament would be elected by counting votes per district. Uitermark’s aim is to strengthen ties with local authorities. ‘This in itself is a laudable goal,’ argues Davide Grossi, Professor of Collective Decision Making and Computation at the University of Groningen, ‘but my main concern with the proposed reform is that the introduction of districts could jeopardize the fundamental principle of proportional representation.’

FSE Science Newsroom | Charlotte Vlek

According to the NSC minister’s new plans, 125 of the 150 seats are to be distributed based on the number of votes per district rather than on national level. Each district, which corresponds to each of the provinces of the Netherlands, will get a roughly proportional amount of seats in the Parliament, depending on the number of inhabitants: for instance, four seats for Groningen versus 21 for Noord-Holland. Because parties have to provide a separate list of candidates for each province, Uitermark hopes that voters will be able to elect local candidates, thus strengthening the ties between national politics and the provinces.

But what effect could this voting per district have on the overall outcome in Parliament? ‘What we know from decades of research in voting theory is that electoral systems are complex, and even well-intended modifications may have negative consequences,’ Grossi explains. One principle that everyone agrees on, including NSC, is that political parties are given seats in Parliament in proportion to the support they receive from voters. Still, the proposed electoral system may violate this basic principle in some cases (see the text box for a simple example).

When counting per district leads to disproportional results

With an example, Grossi illustrates how proportional representation can be affected by counting votes per district. Suppose we have a country that has only two districts: West and East. There are 10 seats in parliament to be allocated. District West is allocated 6 seats, and East is allocated 4. This is because the number of inhabitants of District West is much larger: 600,000 in West versus 400,000 in East.

Two parties are now contesting the elections: New Democracy and Freedom Now. Both in West and East, New Democracy receives a majority of votes: 57% in West (342,000 votes out of 600,000) and almost 60% in East (293,000 votes out of 400,000). However, when seats are allocated per district (using the D’Hondt method as is used in The Netherlands), this majority does not become visible in Parliament. Seats are divided equally over both parties: in West, New Democracy gets 3 seats and Freedom Now gets 3 seats; in East, New Democracy gets 2 seats and Freedom Now gets 2 seats. So, in Parliament, each party gets a total of 5 seats.

With votes counted at the national level, New Democracy would get a majority in Parliament: they obtained a total number of 342,000 + 293,000 votes (a little over 58%), versus 258,000 + 161,000 for Freedom Now (almost 42%). Allocating seats at the national level would get New Democracy 6 seats, and Freedom Now 4 seats.

So, counting per district or counting at a national level leads to different outcomes. In this specific case, a majority of votes does not lead to a majority of seats in parliament when counted per district.

In my opinion, there are other — more effective and less invasive — ways to get citizens more engaged in politics

Grossi summarizes: ‘A party that has a minority of the total votes could even obtain a majority in parliament when votes are counted per district.’ In addition, counting votes per district can have a negative effect on smaller parties. Grossi: ‘Parties whose support ends up being split across districts may not manage to get any seats at the district level, whereas if all the votes are counted at the national level, they may get at least one seat.’

Better solutions

‘In my opinion, there are other — more effective and less invasive — ways to get citizens more engaged in politics,’ Grossi concludes. To strengthen ties with citizens, it would be better for political parties to ensure a fair representation of regional candidates on their candidate lists, so that voters can better express their regional preferences.

‘But it would be even better to give citizens more direct influence on decisions that really matter to them, rather than just asking for their vote once every four years: that is the idea behind participatory democracy.’ With his research group at the University of Groningen, Grossi is developing methods for participatory democracy, collaborating with the municipalities of Groningen and Assen, as well as with software developers from Liquid Feedback and Parta. Grossi: ‘In Assen, for example, young people already have a direct say in how the municipality can make investments that will improve their lives in the city.'

More info:

| Last modified: | 01 April 2025 4.00 p.m. |

More news

-

03 April 2025

IMChip and MimeCure in top 10 of the national Academic Startup Competition

Prof. Tamalika Banerjee’s startup IMChip and Prof. Erik Frijlink and Dr. Luke van der Koog’s startup MimeCure have made it into the top 10 of the national Academic Startup Competition.

-

01 April 2025

‘AiNed’ National Growth Fund grant for speeding adoption of AI at SMEs

Professor Ming Cao receives an ‘AiNed’ Growth Fund grant of EUR 2.4 million for research that will contribute to faster adoption of AI at SMEs in the technical industry in the Netherlands.

-

01 April 2025

'Diversity leads to better science'

In addition to her biological research on ageing, Hannah Dugdale also studies disparities relating to diversity in science. Thanks to the latter, she is one of the two 2024 laureates of the Athena Award, an NWO prize for successful and inspiring...