What is needed to restore the Wadden region?

In the old days, people in the Northern Netherlands fished salmon from the creeks along the Wadden Sea and babies slept on mattresses filled with seagrass (because of its potent antibacterial properties). In addition, the Wadden Sea has always played an important role for fish, birds, and soil life: it serves as a breeding ground, refuelling station, and resting place. However, the Wadden Sea is not doing well. What is the exact state of affairs and what can we do to help nature recover? These are the topics that researchers from the University of Groningen discussed at the closing symposium of the projects Swimway Waddenzee and Waddenmozaïek.

FSE Science Newsroom | Charlotte Vlek

Monitoring by the Royal Netherlands Institute for Marine Research (NIOZ) shows that fish numbers have significantly declined over the past fifty years. ‘Fish have different needs at different stages of their life cycle,’ explains Britas Klemens Eriksson, Professor of Marine Ecology. 'In the Swimway project, we looked at various living environments, how fish make use of them, and what we can do to make them more suitable.’

The project Waddenmozaïek focused specifically on the soil life in the Wadden Sea areas that are permanently underwater: the sublittoral nature. In fact, very little was known about that. Laura Govers, associate professor of Marine Ecology and Nature Conservation, explains: ‘If you dig into the soil, you can find all kinds of things: shellfish, worms, crabs, lobsters. These animals form the foundation of the food web in the area. Without these small ground dwellers, large animals would not be able to survive.’ The goal of the project Waddenmozaïek was to map out the soil life in the submerged areas of the Wadden Sea and find out what it needs to thrive.

Using the findings from the projects, the researchers offer several recommendations for more effective nature conservation in the Wadden area, for example how to create a proper salt marsh and what is needed to reintroduce subtidal seagrass, which forms the foundation of the ecosystem, into the Wadden Sea. Read on to find out the main conclusions drawn from the research.

Salt marshes are important, and here is how we can improve them

In the past, the Wadden Sea coastline used to be winding,’ says Eriksson. ‘There were no dykes and everything was open as far as the city of Groningen, resulting in a gradual shift from saltwater to freshwater, as well as an extensive area that filled with water at high tide and dried up as the tide went out. In those days, northerners used to catch salmon in the creeks that extended inland.’ For many fish, this mix of fresh and saltwater serves as a breeding ground: they head there to reproduce.

On Schiermonnikoog, there are still natural salt marshes, where this gradual transition from freshwater to saltwater occurs. I had never thought there would be such a large number of fish there,’ Eriksson says. ‘Thousands upon thousands of fry are out there. Fish also use the mainland salt marshes, located just outside the dykes of the Wadden Sea coast, PhD student Hannah Charan-Dixon from Eriksson’s group discovered. This is good news. Yet, the natural salt marshes remain the preferred choice. Based on this research, the lessons for nature conservation are: make the mainland salt marshes more appealing to fish by making them more winding, ensuring that they do not empty completely during low tide, and creating a gradual transition from freshwater to saltwater, which is currently lacking. ‘Well, to do that, you would just have to make a hole in the dyke,’ concludes Eriksson.

Keeping count of fish numbers by listening to them

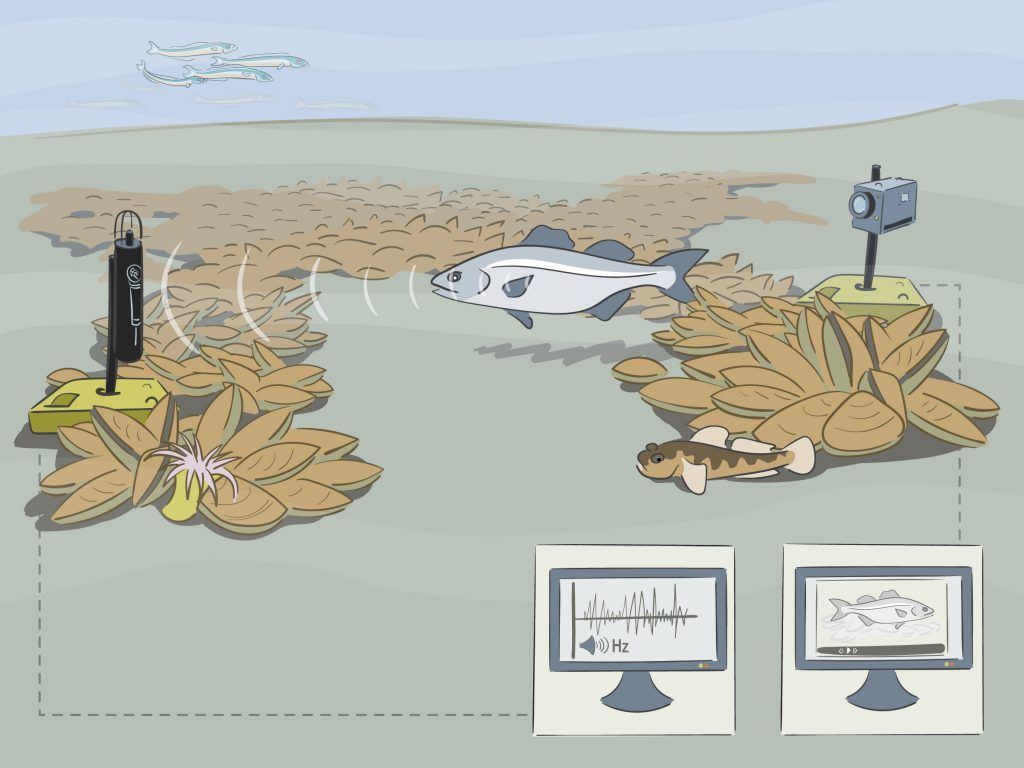

NIOZ researchers monitor fish numbers in the Wadden Sea by systematically catching, counting, and releasing them. ‘But we can only take these samples if the weather is good enough,’ says Annebelle Kok, researcher in Eriksson’s group, ‘and this is quite invasive for the fish.’

Eriksson and Kok experimented with using a hydrophone, an underwater microphone. 'This research was primarily exploratory — to see whether we can get any insights into the population based on the sounds,’ states Kok. And they managed to do so: among other things, they found that creating an artificial reef resulted in more fish sounds, and they identified seal sounds in the recordings and observed a circadian rhythm among the fish present in the area. It is not yet possible to identify specific fish based on their sounds, but that is a follow-up project that Kok intends to work on with the help of AI.

'So, audio definitely has potential as a monitoring tool,’ Eriksson concludes. And the great advantage of it is not only that with audio monitoring, you can leave the fish undisturbed, but you can also take continuous measurements, in any season and at any time of the day. So, you also get a glimpse of the fish behaviour throughout the day. ‘Fish are always active around sunset, a bit like birds chirping in the morning,’ according to Kok and Eriksson.

139 species mapped out

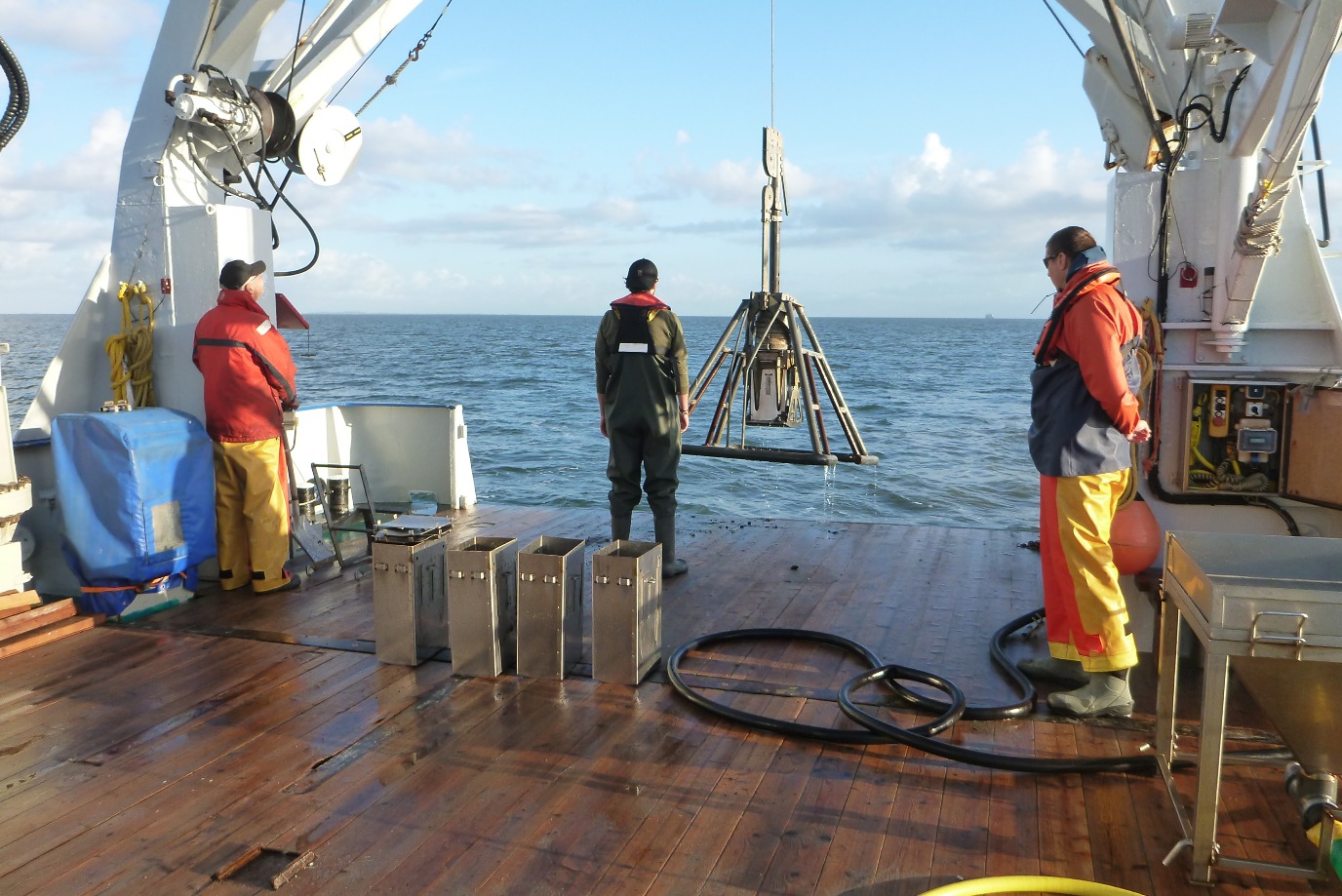

Led by postdoc Oscar Franken, UG and NIOZ researchers took 1323 soil samples, spaced one kilometre apart on a fine-meshed grid. 'We wanted to find out what life is present there, and by looking at how many species there are in a sample, you can also get an idea of the biodiversity,’ according to Govers. They found a total of 139 species. 'So, there is abundant soil life! That’s good. However, it is likely that even more could be possible if we better protect the area, as what we are doing now is not too effective.’

Only two percent of the ecological hotspots are protected

By first mapping out the types of soil life and their locations, PhD student Kasper Meijer was then able to identify so-called ecological hotspots: places that house great biodiversity. ‘We found out that only two percent of the hotspots are located in areas protected by internationally accepted standards,’ explains Govers.

‘At present, primarily low-dynamic areas are being protected— the areas that see relatively few waves. Whereas we have, in fact, observed that even in high-dynamic areas there is also a wealth of live, and possibly also soil life that is not found in low-dynamic parts. In addition, there are ecological hotspots that are partly protected, but where various human activities still take place.

‘There was still very little knowledge about what lives in the submerged ecosystems of the Wadden Sea,’ states Govers. Nature conservation always involves a trade-off between many factors, including the knowledge available, fishing, and recreation. ‘We hope that nature can now be better considered in that trade-off, now that we know more about it.’

Reintroducing subtidal seagrass into the Wadden Sea: there are possibilities

Govers has researched seagrass for years and has achieved various successes with intertidal seagrass. But subtidal seagrass is a whole different matter. Where once around 150 square kilometres of the Wadden Sea were covered by seagrass, all subtidal seagrass has completely disappeared since the 1930s.

Using models, PhD student Katrin Rehlmeyer examined whether suitable conditions for seagrass growth exist in the Wadden Sea at all. These days, the Wadden Sea is much cloudier than it used to be. ‘But there are a few small patches that would suit,’ says Govers. It covers a total area of around six square kilometres, which is less than one percent of the subtidal Wadden Sea. 'Still, it gives hope.’

The researches also experimented with measures aimed at reintroducing seagrass to these areas. Seagrass is a true bio-builder: in a large seagrass meadow, the plants themselves make sure that the soil stays in the right place by forming root mats, similar to grass sods, and that currents are dampened. Govers and colleagues attempted to replicate this by stabilizing the soil with so-called potato mats, and using sandbags to reduce the flow.

The sandbags did not quite produce the desired effect, as all sorts of eddies actually formed around the wall of bags, reports Govers. ‘But stabilizing the soil had a positive effect — it extended the plants’ lifespan, even though they eventually died. But now we know that there are possibilities, even though it will not be easy to reintroduce subtidal seagrass to the Wadden Sea.’

Both the Swimway Waddenzee and Waddenmozaïek projects were collaborations between UG staff members and other knowledge institutions, nature managers, and nature conservationists. Thanks to these collaborations, it was possible to conduct small-scale experiments with nature conservation measures. ‘It worked very well,’ states Govers. 'The nature conservationists asked critical questions that we, as researchers, had not always considered, and we made sure that the new measures were supported by scientific evidence.’

On 24 April, Laura Govers will speak at the Kenniscafé Een streep door de Wadden. More information and tickets: Studium Generale.

On 26 April, the Wadden Sea World Heritage Centre (Werelderfgoedcentrum Waddenzee, WEC) will open its doors to the public. The WEC is based in the port of Lauwersoog and is a continuation of the Pieterburen Seal Rehabilitation and Research Centre, but in a new form. The WEC reveals the beauty and vulnerability of the Wadden Sea and works towards a better balance between humans and nature. The WEC also features recordings of fishing sounds captured by Eriksson and Kok. More information is available on the WEC website.