Mapping favouritism at the Eurovision Song Contest: does it impact the results?

Ever since the Eurovision Song Contest exists, there are suspicions that the voting is politically biased. Based on the most recent 45 editions, this paper maps out which participating countries can count on each other's sympathy and which cannot. Although there are clear preferences between countries, political voting rarely determines the overall result and the best entry wins. Corrected for favouritism, Sweden is the most successful country and 'Save your Kisses for me' is the 'best' song since 1975.

By Felix Pot

In short:

- By analysing the results of 45 editions of Eurovision, clear geographical voting patterns emerge

- Countries in the Caucasus and the Balkans benefit the most from political voting

- Rarely is political voting decisive for the outcome of the Eurovision Song Contest

- Adjusted for favouritism, Sweden is the best Eurovision country

- The highest valued Eurovision song is "Save Your Kisses for Me" by Brotherhood of Man

The Eurovision Song Contest has been an annual European tradition since 1956. Thanks to the Dutch win in 2019, the mega-fest will land in Rotterdam in 2021. Eurovsion was created to bring together a Europe torn apart by two world wars through the power of music. Slogans such as 'Under the same Sky' (Istanbul, 2004) and 'Building Bridges' (Vienna, 2015) underline this pan-European ambition of unity.

At the same time, Eurovision is a competition in which countries try to show their best (European) side, break social taboos and/or address political sensitivities between countries (Yair, 2018). These national expressions are then rewarded or punished by the European public through voting. Ever since Eurovision has existed, there have been allegations of favouritism in voting. Countries would give each other points not only based on the song, but also on affinity (Stockemer et al. 2018). In case Greece will be in the final on 22 May 2021, it would be very surprising for it not to receive the full ‘douze points’ from Cyprus. Other groups of countries such as the Baltic States, countries in the Balkans and the former Soviet states are also accused of exchanging votes (Dekker, 2007; Fenn et al., 2006; Yair, 1995; Yair and Maman, 1996). Explanations include cultural similarities, a shared political history and ethnic ties through migration (Ginsburgh and Noury, 2008; Spierdijk and Vellekoop, 2009). Eurovision thus appears to be not only an entertaining event for many, but also an annual poll of how relations are developing on the European continent. Is this political voting behaviour indeed present and to what extent does it influence the outcome? And what are the best songs and countries of the Song Contest, barring any favouritism? This article summarizes an analysis based on the past 45 editions.

Quality and affinity

The rules of Eurovision are simple: each participating country enters a song which is then awarded 0 to 12 points by all other contesting countries. In order to map the voting bias, it must first be determined which part of the awarded points is related to the quality of the song and which part to affinity with the country. Of course, there is no accounting for taste, especially at Eurovision. Still, there is a way to separate these two components. It is justifiable that the quality of a song is equal to the average number of points it receives. The problem is that this average would include political votes. By analysing results over the entire period that the current points system exists (1975-2019), it can be seen whether a country systematically gives an above or below average number of points to another country. If this is the case, it can be said that this country is not a neutral evaluator of the other country. To arrive at a measure of quality for an entry based on the average number of points received, only neutral assessors of that country are included. In other words, to measure the quality of a Greek entry by the average number of points received, for example, the points awarded by Cyprus are not taken into account. Accordingly, a quality score can be calculated for each song.

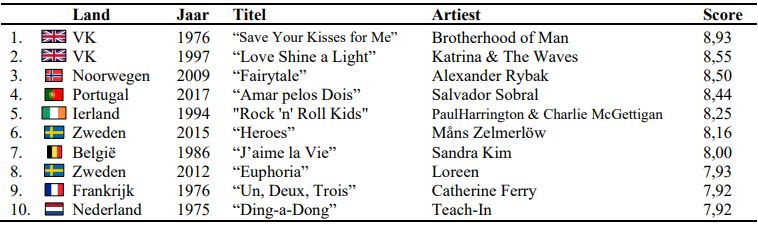

Table 1 shows that, based on this method, "Save your kisses for me" by Brotherhood of Man is the highest-rated song over the period 1975-2019 (a top 100 can be found in the Appendix). The Dutch entry "Ding-a-Dong" closes the top 10. If a country gives more or less points than this quality score, this can be seen as an over- or undervaluation (Fiebelmayr and Toubal, 2010; Ginsburgh and Noury, 2008).

Mental maps of Europe

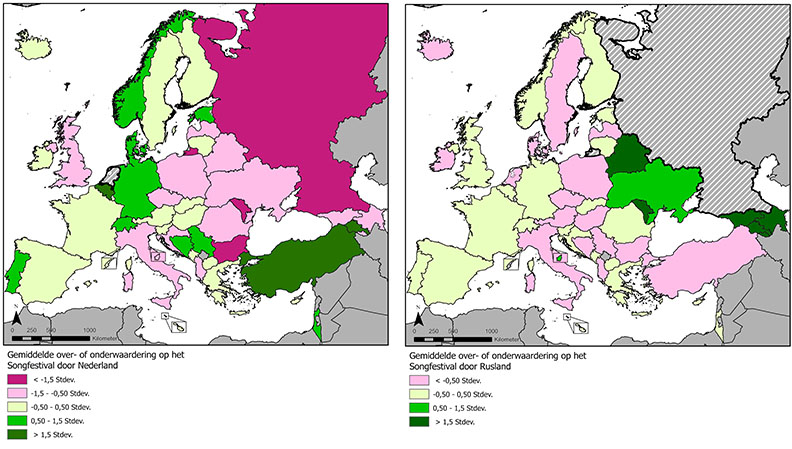

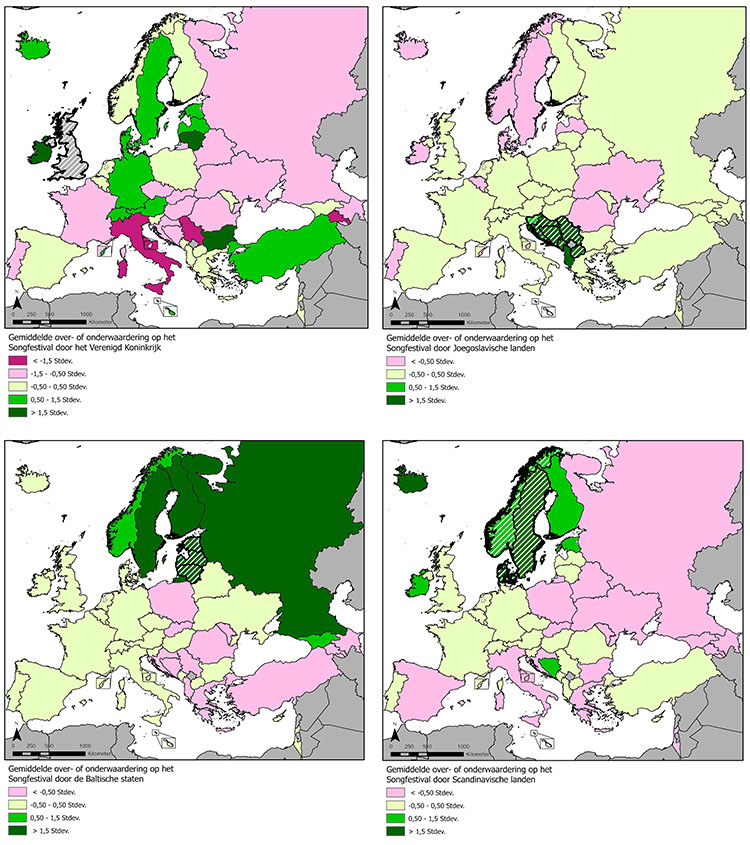

The maps below show the average over- and underestimation of one country or a group of countries to all other (ex-)participating European countries (Figures 1 and 2). To facilitate comparison between the maps, the ratings are presented in standard deviations. Light green reflects a more or less neutral attitude. The greener the more positive and the pinker the more negative (a more detailed breakdown of voting biases can be found in the Appendix).

The Netherlands clearly gives more votes to its neighbouring countries, Belgium and, to a lesser extent, Germany. Many votes also went to Turkey and Armenia. This is a phenomenon that also occurs in other West European countries, such as Germany and Belgium, due to the presence of a relatively large population with these origins (Spierdijk and Vellekoop, 2009). Eastern European countries, and especially Moldova, Bulgaria and Russia, get the least support from the Netherlands.

The 'mental map' of Russia looks very different. Here it is mainly the former Soviet states in the Caucasus and Eastern Europe (Belarus, Ukraine and Moldova) that are overvalued. It is striking that the former Eastern Bloc countries that are now part of the European Union do receive any overvaluations from Russia. These countries themselves have also given less and less overvaluations to Russia, and since 2014 they have on average not even given overvaluations to Russia anymore.

The United Kingdom is also interesting to look at, as this country has recently broken with Europe politically. The UK is also traditionally one of the biggest critics of the Eurovision voting system. Yet, the UK is not immune to political voting either, given the strong preference for neighbouring Ireland. Again, the influences of labour migration can be seen with overvaluations for Bulgaria and Lithuania as well as the influence of political history with positive ratings for Malta and, not visible on the map, Australia.

Perhaps the biggest accusations of favouritism at Eurovision go to the Balkan countries. Indeed, it is easy to see that countries of the former Republic of Yugoslavia trade points. A similar pattern can be seen for the Baltic States, although points are also given to Russia and the Scandinavian countries. The latter also seems to form a bloc with Iceland and Finland. Many points also go to Bosnia and Herzegovina due to the relatively large number of Bosnians in Sweden in particular.

Often, the focus is on bloc formation between countries that vote for each other. But it is just as interesting to look at the undervaluations. As might be expected, Armenia and Azerbaijan hardly trade points. But it does not always take war. For instance, there is little exchange between Islamic (e.g. Turkey and Azerbaijan) and Christian countries (e.g. Serbia and Poland). Also striking is the undervaluation of Italy by many (ex) EU countries. The United Kingdom, Bulgaria, Hungary and Estonia, for example, systematically give Italy fewer points.

Political voting not decisive

It is clear that there is bloc formation and favouritism in the Song Contest. The Balkans and the Caucasus benefit the most from this. These countries dominate the top 10 of countries that receive the most over-rating across the board. The question then arises whether this is problematic. It seems that the influence of political voting on the final result is actually limited. After all, if the same cultural factors were at play every year, only a limited group of countries would be able to win. The fact that there is a great diversity of winning countries, even after the accession of Balkan countries, former Soviet states and Eastern European countries, suggests that this is not true. Previous research has also shown that the quality of a song is decisive (Ginsburgh and Noury, 2008). Despite bloc formation, for an entry to win it should appeal to everyone to at least some extent.

Using the song scores that have been cleared for favouritism, it appears that since 1990 the song with the highest quality score has not won four times. All times seem to be incidents. In 1991 there was a tie between Sweden and France and the winner was determined by counting the number of 12- and 10-pointers. In 1998, the UK had the best song judging by the scores of neutral countries, but lost to Israeli taboo-breaking Dana International, who was the first openly transgendered person to perform at the Song Contest. In 2000, Russia lost to Denmark after the Russian delegation accused the Danes of cheating for using a vocoder on stage. Most recently, in 2016, Ukraine won from favourite Russia with a song about Stalin's deportation of Crimean Tartars in 1944. Analogies were quickly drawn with the current occupation of Crimea, resulting in strong undervaluations for Russia in that year.

The best Eurovision country?

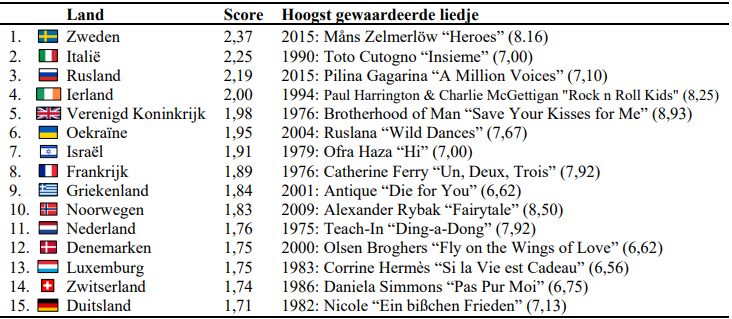

What if there were no favouritism, which country would come out on top? Below is a ranking of countries based on song ratings by countries that are neutral towards that country (the full list is in the Appendix). A correction has also been made for the number of participations a country has. After all, if a country has participated three times and scored very well three times, that does not mean that that country is just as good as a country that has participated ten times and always scored equally well. When calculating the average score of a country, the score of a country that has participated less often is drawn to the average of all songs across all countries. In other words, if a country did not participate, it is implicitly assumed that a country would have sent in an average song (for a detailed explanation of this method, see: Bhayani, 2020).

Based on these calculations, Sweden is the best Eurovision country, even without accounting for ABBA's victory in 1974. Italy, which served as a role model for the Song Contest with the San Remo Festival, occupies second place and the third place is for Russia. Although Ireland and the United Kingdom have not been particularly successful in recent years, they still rank high on the list due to past successes. The overall rankings do change slightly if favouritism is not controlled for. However, the overall structure is very similar and Sweden remains number one. This, again, underlines that favouritism only has a modest impact on Eurovision results.

‘Music first’

Despite the Song Contest's pan-European motivation, there seems to be little evidence of broad-based European unity. Analyses of voting results reveal clear geographical voting patterns that can be traced back to cultural, religious, political and ethnic ties. Yet the fear of an unfair festival is not entirely well-founded. It may push a country through the semi-finals, but the Contest will unlikely be won on the basis of favouritism alone. There seems to be some truth in Duncan Laurence's victory speech in Tel-Aviv in 2019. It is all about “music first”.

References

Bhayani, A. (2020). Solving an age-old problem using Bayesian Average. www.codementor.io

Dekker, A. (2007). The Eurovision Song Contest as a ‘Friendship’ Network. Connections, 27(3), 53-58

Fenn, D., Suleman, O., Efstathiou J. and Johnson, N.F. (2006). How does Europe make its mind up? Connections, cliques, and compatibility between countries in the Eurovision Song Contest. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and Its Applications , 360, 576–598

Felbermayr, G.J. and Toubal, F. (2010). Cultural proximity and trade. European Economic Review, 54, 279-293

Ginsburgh, V. and Noury, A.G. (2008). The Eurovision Song Contest. Is voting political or cultural? European Journal of Political Economy, 24(1), 41–52

Spierdijk, L. and Vellekoop, M. (2009). The structure of bias in peer voting systems: lessons from the Eurovision Song Contest. Empirical Economics, 36, 403-425

Stockemer, D., Blais, A., Kostelka, F. and Chhim, C. (2018). Voting in the Eurovision Song Contest. Politics, 38(4), 418-442

Yair, G. (1995). Unite Unite Europe’: The political and cultural structure of Europe as reflected in the Eurovision Song Contest. Social Networks, 17, 147–161.

Yair, G. (2018). Douze point: Eurovisions and Euro-Divisions in the Eurovision Song Contest – Review of two decades of research. European Journal of Cultural Studies, 22 (5-6), 1013-1029

Yair, G. and Maman, D. (1996). The persistent structure of hegemony: Politics and culture in the Eurovision Song Contest. Acta Sociologica, 39(3), 309–325

Appendices

More news

-

01 December 2025

The power of movement

-

24 November 2025

RUG en Ministerie van I&W starten brede meerjarige samenwerking