Research Digest: Practicing Philosophy from Fryslân to the Far East

| Date: | 19 November 2024 |

| Author: | Friso Timmenga |

The Research Digest series continues, where our faculty members share insights into their research and the broader societal issues they tackle. This time, Friso Timmenga brings us a contribution from the Far East. Reflecting on his research stay at Osaka University, Friso explores the question: Why study Japanese philosophy in Japan when it can be learned from afar? He examines how philosophy is shaped by its cultural context and argues that it’s not just about universal truths, but a practice that evolves through engagement. Drawing from his time in Japan, Friso emphasizes the importance of experiencing philosophy through lived practice, as seen in traditions like Zen. He also highlights how embracing local perspectives, like those at Campus Fryslân, helps connect global ideas with local realities. Curious to see if his reflections resonate with you? Read on and join the conversation!

“So what are you going to do in Japan?” “I am going on a research stay at the philosophy department of Osaka University.” “Yes, but what are you actually going to do there?” In the months leading up to my research stay in Osaka, I found myself reflecting on this question many times. As a philosopher, my methods usually involve reading books and writing papers, so the question is a valid one. What could I possibly learn about Japanese philosophy in Osaka that I couldn’t learn from behind my desk in Leeuwarden?

Philosophy aims at universal and absolute truths, or so we often assume. This is why we can still engage with the works of Plato and Kant – they offer insights that transcend space and time. You don’t need to travel to ancient Greece or 18th-century Germany to grasp their ideas. So why travel all the way to Japan to study Japanese philosophy?

While this universalistic view holds some truth, it overlooks a crucial aspect of philosophy: it is always shaped by its specific context. The deeper we delve into a philosopher’s ideas, the more important that context becomes. That is why one of the key questions in philosophy is: how can a local idea claim absolute status? In other words, how does the particular transform itself into the universal?

This question is very much at the centre of contemporary Latin-American, African, and Asian philosophy. That is because, unlike the ‘standard’ European philosophy, these traditions constantly have to justify their own existence as philosophy in the academic world. When their methods diverge from European standards, they risk being dismissed as poetry, anthropology, or religion. But if they conform too closely to those standards, they are asked what makes them distinctly Latin-American, African, or Asian. They are either too different or too similar.

As I sought to point out above, this dichotomy is false. The fact that an intellectual tradition is deeply rooted in a particular culture, doesn’t mean that its insights are only relevant for that particular culture. Conversely, a tradition that claims universality too hastily might overlook the more ‘provincial’ elements in its own discourse.

What can we conclude from this observation? Perhaps that the question of whether philosophical ideas are universally valid or not is the wrong one. Another, more interesting question will arise if we draw attention to the fact that philosophy isn’t just something that resides in books on a shelf. Rather, it lives in discussions and classrooms. Philosophy is fundamentally something we do – it is a practice that seeks personal transformation through argument and reflection.

Rather than about being universal or not, philosophy is about becoming universal. Therefore, the more interesting question is: which philosophical practices actually foster this universality? This transformative aim is especially clear in the field of ethics. The ethics classes I teach in the GRL programme do not merely aim for students to internalize philosophical proposition X or Y (although there is some of that as well – I admit!), but to challenge them to adopt a viewpoint that transcends their own selves in the here and now as the basis for ethical conduct.

❝The ethics classes I teach in the GRL programme do not merely aim for students to internalize philosophical proposition X or Y (although there is some of that as well – I admit!), but to challenge them to adopt a viewpoint that transcends their own selves in the here and now as the basis for ethical conduct.❞

True to the original meaning of the word, the philosopher seeks wisdom and practices it, though can rarely claim to fully possess it. Philosophical practice is thus a continuous process of becoming, moving from a limited, narrow view of reality toward a broader, more encompassing perspective. The acknowledgement of this continuity between contextuality and universality should prompt us to ask: What practices are actually conducive to philosophical insights? Who engages in them? Where do they take place?

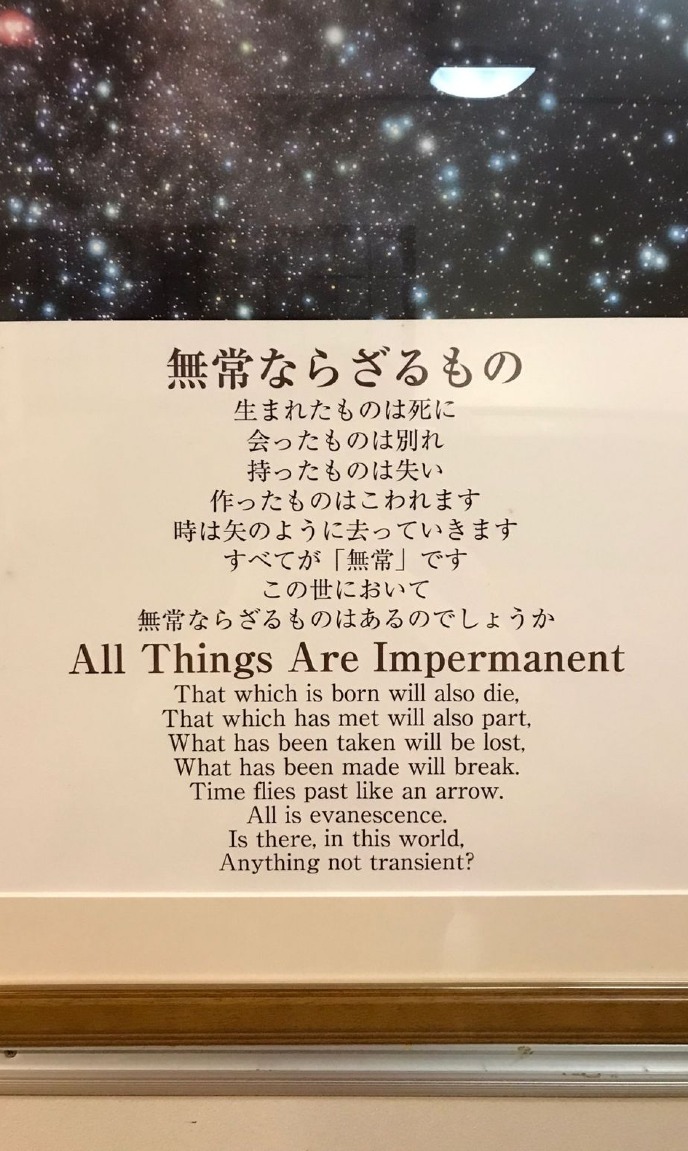

This practical aspect is even more evident in traditional Japanese philosophies like Zen. To truly understand Zen Buddhism, familiarizing yourself with the teachings in a book is not enough: you must engage in its embodied practice (as the Zen tradition itself claims).

In some ways, the modern university shares similarities with a Zen temple. Universities have their own clergy (professors) who preside over rituals (lectures, discussions, conferences) that students must participate in as part of their initiation (earning a diploma).

I am now able to answer my initial question. Why am I in Japan? To study the practice of wisdom, beyond theory. I want to learn how philosophy is taught, who engages in it, what the curriculum entails. These are all deeply contextual matters, yet they are essential to understanding Japanese philosophy in a broader sense.

I can truly say that it was Campus Fryslân that taught me not to be blind to context. Perhaps it is because we are an ‘outsider’ relative to Groningen that our faculty in Leeuwarden never loses sight of the importance of place. It is why Campus Fryslân has such strong ties to partners in the region and seeks to respond to global problems via local solutions.

So, as strange as it sounds, when I walk through a Japanese temple or study Japanese philosophy, I often think of Leeuwarden. I see how art and wisdom, deeply rooted in local realities, can inspire someone who has travelled over 9,000 kilometres to encounter them. Paradoxically, it is precisely when we embrace local context, that Fryslân truly meets the Far East.

Curious about Friso's research? Don’t miss this!

About the author

Friso Timmenga is a PhD candidate at Campus Fryslân whose expertise lies in the exploration of world philosophies and epistemic diversity, with a particular focus on their methodological and educational dimensions. He was appointed as one of the Faces of Science and is a regular contributor to philisophical webzine Bij Nader Inzien. Through scholarly pursuits and experience in education, Friso's goal is to foster a more diverse and decolonized philosophical landscape.

> View Friso's full profile