Building top-notch telescopes to look into our past

UG professor Scott Trager is developing new methods to unravel the evolution of stars in the Milky Way – and of galaxies far away. ‘There is a sense of wonder in looking out at the universe and thinking: how did this come to be? How does it all work?’

Text: Nienke Beintema / Photos: Reyer Boxem

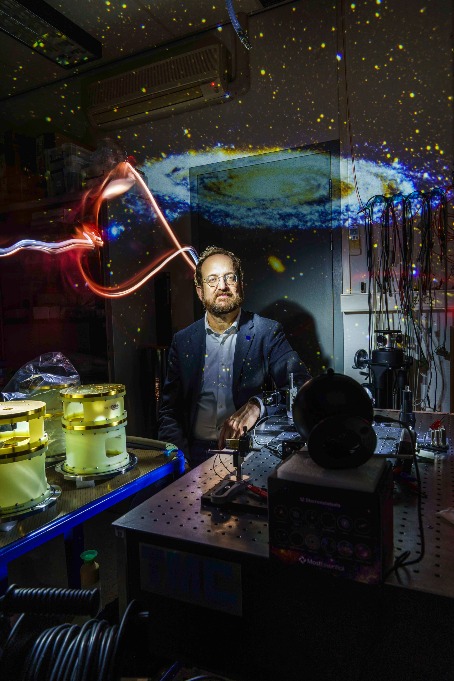

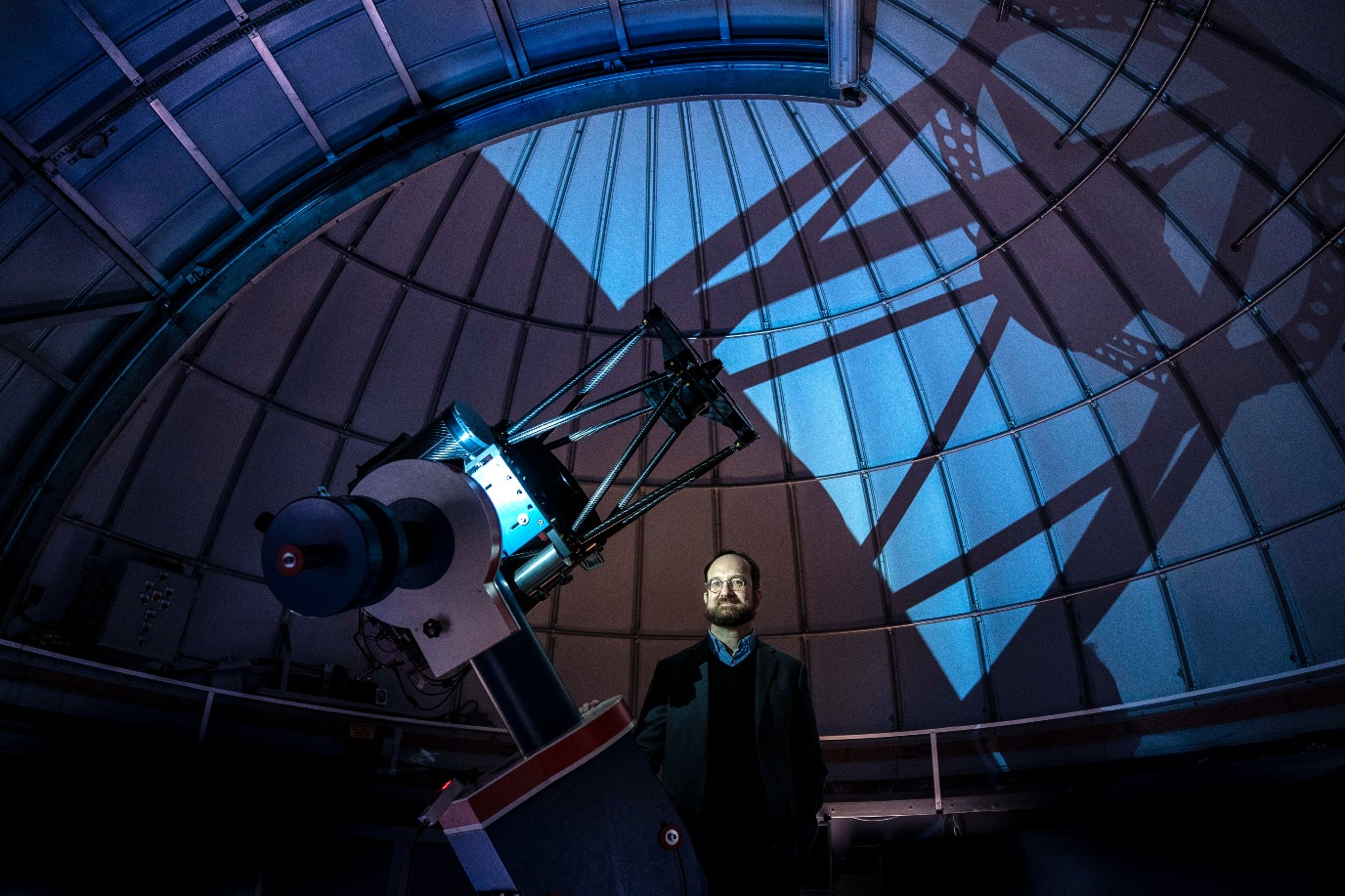

'For as long as I can remember, I have wanted to know how things work', says astronomer Scott Trager in his study at the Zernike Complex. 'I also loved everything that had to do with stars and galaxies and the universe in general. As a kid I did have a telescope, yes, but within three days I had taken it apart, just to figure out how it worked. I never put it back together.' He chuckles. Trager’s drive as an astronomer has two sides. Yes, he wants to know ‘how the universe works’, and how it came to be, but he is equally interested in the methodologies to figure that out. 'It’s the combination that fascinates me', he says. 'And that is why the RUG’s Kapteyn Institute is the right place for me. I get to work at the interface of fundamental astrophysics and the development of world-class telescopes and models.' Trager, originally from California (US), has been living in Groningen since 2002. In March 2024, he delivered his inaugural lecture for his professorship in ‘Evolution of and Stellar Populations in Elliptical Galaxies and Instrumentation’ – a Chair that unites his two passions.

Why did you choose The Netherlands?

'The Kapteyn Institute has been world-renowned for decades. I clearly remember reading top-level research papers from this institute when I was a PhD student in California. Those preprints from Groningen, with their black-and-yellow logo, were the ones to look out for. That somehow stuck in my head. Then in 1995, I attended a conference of the International Astronomical Union in The Hague, my first big professional meeting. I talked to many of the Kapteyn researchers, which was very inspiring. And then I spent a week driving around the Netherlands. I thought: ‘This is a great place. I think I would like to live here.''

And that worked out nicely?

'Yes, in 2001 this position was advertised, exactly in the field that I was most interested in. I was lucky enough to get the position. And I still love it. I feel very much part of the academic environment and the city. The RUG is right where I need to be, and the Kapteyn Institute is wonderful. Just how I imagined it would be.'

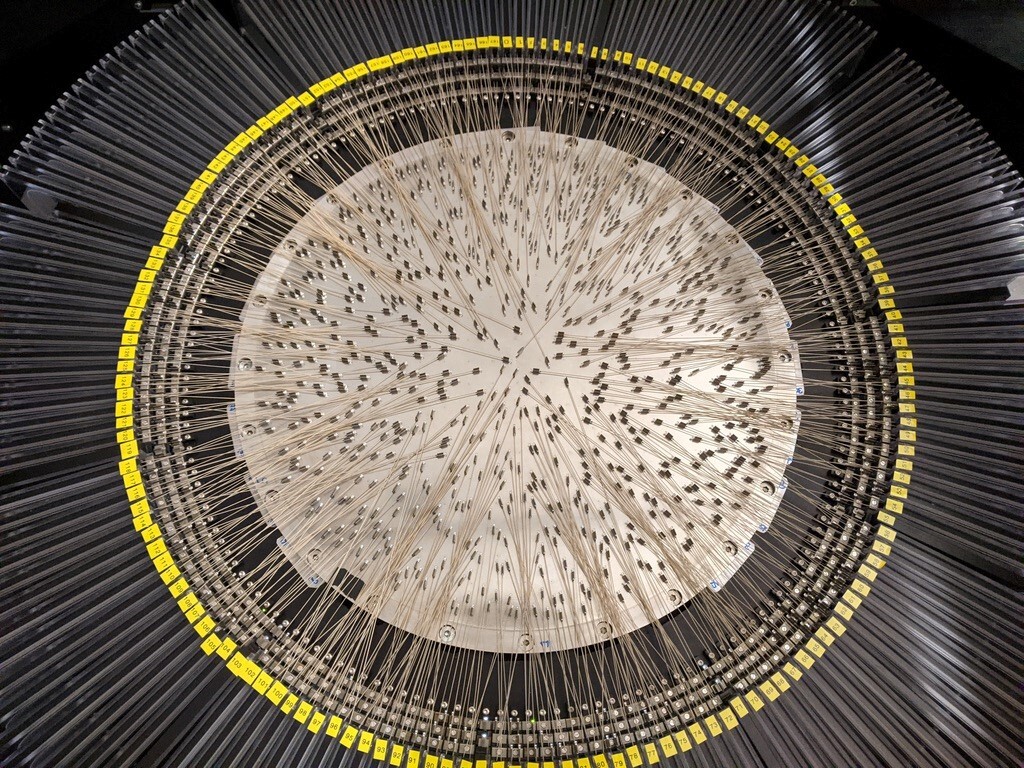

You are one of the main developers of WEAVE, an instrument mounted at the William Herschel Telescope (WHT) in La Palma, Canary Islands. What does WEAVE do?

'WEAVE stands for WHT Enhanced Area Velocity Explorer. It captures the light of around 1000 stars simultaneously. Moveable glass fibres are pointed at individual stars in the Milky Way and then transport their light to a spectrograph, a machine that unravels the incoming light into its separate wavelengths. This gives us a ‘fingerprint’ for each star. This fingerprint tells us exactly what the star is made of and how fast it travels. You can also point the instrument at entire galaxies outside of the Milky Way, to unravel their light spectrums.'

Why do you want to know the composition of stars or galaxies?

'This information helps us to reconstruct the evolution of these stars or galaxies – and ultimately, of the universe as a whole. It tells us what happened to them, and why they look the way they do. Some galaxies look like our own: a disc with spiral arms. Some look more like a ball, or a sausage, a flying saucer or a fried egg.' In fact, Trager uses the Dutch words for typically Dutch food items: ‘eierbal’, ‘kroket’, ‘poffertje’ and spiegelei, respectively. 'That’s because I like food', he explains with a grin, 'and because it’s nice to explain it to my students this way.'

How does the shape of a galaxy relate to its history?

'If a galaxy is shaped like an eierbal or a kroket, it turns out that its stars are almost always red and therefore old. If it’s shaped like a poffertje or a spiegelei, then it’s almost always blue and therefore younger. To really determine how old they are and what they’re made of, you need to break up the light into the different wavelengths. That’s what WEAVE does, at a really high resolution. This tells you, for instance, if this galaxy resulted from two galaxies smashing into each other, or from a bigger galaxy collecting many smaller things.'

Are these processes still happening?

'Yes, but much slower now. Most of this happened when the universe was only a quarter to a third of its current age (which is around 14 billion years). The last big merger involving our Milky Way was around 8 billion years ago, according to new data from the Gaia satellite. Our Milky Way will probably merge with our sister galaxy, Andromeda, in about 1 to 2 billion years. But as we speak, a dwarf galaxy called Sagittarius is actually merging with the Milky Way. It happens all the time.'

What is your own role in all of this research?

'The basic technology of WEAVE was developed and used already in the 1980s. For the past 14 years I have helped to adapt this technology for its current use in La Palma. I work together with some amazing engineers who actually build this stuff, based on what we want to know. My role as an astrophysicist is to provide the engineers with that knowledge. It is a back-and-forth process, really, in which we address both the technological and the fundamental questions at the same time, advancing both fields along the way. Very exciting. In addition, I develop some of the computer models that we use to analyse the data.'

Back to a more fundamental question – why do you want to know the history of the universe…?

'It is really an ‘origins’ question. We all want to know where we came from, right? How did we come to this – living on this habitable planet, in this solar system, in this galaxy, at this point in time? There is a sense of wonder in looking out at the universe and thinking: how is that possible? How does it all work? We are but a tiny speck in the universe, but at the same time, we’re a tiny speck that knows how to ask these questions and how to find the answers. Isn’t that amazing? We all seek some comfort in understanding why we’re here. Astronomy is a way of approaching this – of trying to understand the processes involved in how we became us. It is cool to work in a field where you can address all of these questions.'

That’s all very philosophical, for a physicist!

'Yes, but at the same time, there’s a very practical side. The tools we develop have these amazing spin-offs – like better memory systems for computers, and better cameras for your iPhone. Smartphones have sensors that were originally developed for telescopes. The concept behind WiFi was developed to multiply signals coming from telescopes. In fact, our whole understanding of the basic concepts of physics, like gravity, comes from understanding how planets move. And the basics of quantum mechanics, which are also used in your smartphone, come from our trying to understand why stars shine the way they do.'

Lots of useful applications…

'Absolutely. But all of this is also just very cool and fun. You get to look at pretty pictures and literally peek into the past. And then there’s the scientific excitement of wondering: is this the right way of looking at this question? To discover something new with an instrument that you built yourself… it doesn’t get much better than that.'

Scott Trager (California, US, 1969) studied physics and astronomy at the University of California in Berkeley and Santa Cruz, obtaining his PhD in 1997. He spent five years at the Observatories of the Carnegie Institution of Washington, located in Pasadena, California. In 2002, he joined the Kapteyn Institute of the Rijksuniversiteit Groningen to teach astronomy, facilitate the building of world-class astronomical instrumentation, and study the evolution of the most-massive galaxies in the universe. Trager became a Professor in 2015, but held his inaugurational speech in March 2024.

This article has been taken from our alumni magazine Broerstraat 5.

More information

More news

-

26 January 2026

Science for Society | The AI chip of the future