Making a splash in whale research

He disliked genetics as an undergraduate and never really wanted to work with whales. Yet, Per Palsbøll became a worldwide expert in the genetics of marine mammals, heading a research programme spanning the entire globe. Introducing the concept of genetic tagging, he used genetic tools to identify individuals in species that are difficult to capture and tag. Careful analysis is what he strives for: not bold statements in the media, but rigorous research.

Text: Annemieke van der Kolk, Communication UG / Photos: Daniël Houben

Taking a shot at whales

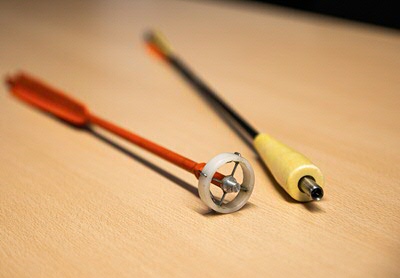

He had to punch a hole in the first whale he ever laid eyes upon, says Per Palsbøll, Professor in Marine Evolution and Conservation with an expertise in the genetics of marine mammals. His supervisor at the time, Finn Larsen, was developing a system using a crossbow and arrows to collect skin biopsies from free-ranging whales without harming them. ‘Once it was known that my grandfather took me hunting when I was young, I was asked to help develop this system further.’ Palsbøll shows me two biopsy arrows: ‘This is an early prototype and the final version, which is used by whale researchers all over the world now. I must admit, taking a skin biopsy from the first whale I ever saw in my life, was quite a baptism into the field. It was a humpback, in Greenland among icebergs.’

DNA mutations

From his modern office with a view on the green Groningen rural landscape, an ocean away from his research objects, he explains what it meant to be educated as a biologist in Denmark. During his studies Palsbøll - a quiet bespectacled man, putting things in perspective with smiling eyes - met an older fellow student: ‘A rather provocative type, who suggested I look into a new method to directly study mutations in the DNA itself. Although I disliked genetics, which for me meant studying yeast in petri dishes, I found this use of genetics was both new and exciting.’

Whale watching

‘The theory of population genetics is very well developed and it’s a research field based solidly on logic, which suits me.’ During his PhD Palsbøll managed to implement the newest lab methods, which some other fellow whale researchers struggled with at the time. He also developed new genetic markers to identify individual whales and their sex. The use of these markers represents a viable alternative to traditional methods of individual identification. The Palsbøll lab now curates a large collection of marine mammal samples. Among the samples are 9,000 skin samples from humpback whales in the North-Atlantic, from a population last estimated at around 12,000 individuals.

Genetic tagging

Palsbøll, then a recent PhD graduate, was asked by a major, coordinated research consortium to lead and undertake the genetic analyses of humpback whale samples collected across the North Atlantic. During the project it became apparent to Palsbøll that he could use genetic analysis of the skin biopsies to identify individuals and with such data estimate how many whales there were in the North Atlantic. ‘We were the first group to estimate how many animals were out there based solely upon “genetic tagging”, as it’s called.’ This CSI-style DNA identification was an important breakthrough and today genetic tagging is used in all kinds of species, marine and terrestrial. ‘It was published in Nature and basically catapulted my career and hire into a tenure-track position at the University of California in Berkeley.’

Climate change threat

What about the effects of climate change? ‘ Currently, the whales are doing very well and may even benefit from some aspects of global warming. But that will probably only last as long as there is ice, since the annual algal blooms and krill depend on the spring ice melt. As soon as the ice disappears, this annual cycle will be broken and whales are likely to suffer. If I had to make an educated guess, I believe we will witness a crash of the cycle in 30 to 50 years, or whenever it is predicted the polar summer ice is no more.’ He ruefully and ironically chuckles and adds: ‘You really don’t need to be a rocket scientist to see that one coming.’

More cells, no cancer

Since size and age are both risk factors in the development of cancer due to the larger number of cell divisions, one would assume that whales are prone to cancer. But they’re not. Why? Palsbøll and his colleagues discovered that some key genes are copied many times in the whale genome. Some of the copied genes are the same genes that protect humans against cancer. Palsbøll will not jump to any conclusions about gained insights into cancer: ‘The plan is to collect skin samples again, grow cell cultures from the skin, and then challenge those skin cells. Then it should be possible to see if the lower rate of cancer is indeed due to an elevated expression of these repeated genes. So far these are only working hypotheses that we need to test.’

Shooting from the hip

‘In my field, the research is often published rapidly and findings that essentially are hypotheses, presented as proof. This process is due to the immense pressure on high research output. This is especially visible in my areas, such as genomics. However, new, emerging research areas need to “mature”, as we often later realize that early applications were based upon naïve or incorrect assumptions and theory.’ Shooting from the hip, is how he sees it and the quiet man with his calm voice becomes a little agitated. Palsbøll is not giving in, though: ‘This may not be all that sexy, but I am proud of the careful analyses in our group, and that we take the necessary time and effort to carefully grind away at the research questions. In genomics, we generate massive amounts of data and apply many assumptions, which need to be checked thoroughly to ensure the conclusions are robust. This sometimes means publishing slowly. We are not trying to be sensational. Our goal is to try to understand what’s going on.’

Birds that live in the ocean

Another of his concerns is that science is becoming more and more influenced by its potential political impact, tempting academics to promote politically popular outcomes in order to increase exposure and funding. ‘At times I am concerned about the rigour of the science. In today’s fast-paced effervescent society, we must continue to consider our research very carefully.’ He then laughs and suggests: ‘In order to garner more Dutch funding maybe I should liken whales to birds that live in the ocean. It seems that the Dutch love their birds, so the analogy might help.’

Read the Palsbøll group’s latest publication about the cause of greatly reduced genetic diversity in Mexican fin whales

| Last modified: | 11 May 2020 11.05 a.m. |

More news

-

13 May 2024

‘The colourful cells of petals never get boring!’

Most people will enjoy colours in nature. However, the interest of evolutionary biologist Casper van der Kooi goes much further: he studies how flowers, birds, butterflies, and beetles get their colours. He also studies how these colours are used...

-

13 May 2024

Trapping molecules

In his laboratory, physicist Steven Hoekstra is building an experimental set-up made of two parts: one that produces barium fluoride molecules, and a second part that traps the molecules and brings them to an almost complete standstill so they can...

-

07 May 2024

Lecture with soon to be Honorary Doctor Gerrit Hiemstra on May 24

In celebration of his honorary doctorate, FSE has invited Hiemstra to give a lecture entitled ‘Science, let's talk about it’ on the morning of 24 May